William Blake, Ancient of Days,, 1794. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

William Blake (November 28, 1757 - August 12, 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. While he was largely unrecognised during his lifetime, his work is today considered seminal and significant in the history of both poetry and the visual arts. According to Northrop Frye, who undertook a study of Blake's entire poetic opus, his prophetic poems form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language ." Others have praised Blake's visual artistry, at least one modern critic proclaiming Blake "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced."[1]

While his visual art and written poetry are usually considered separately, Blake often employed them in concert to create a product that at once defied and superseded convention. Though he believed himself able to converse aloud with Old Testament prophets, and despite his work in illustrating the Book of Job, Blake's Christian beliefs were modified by a fascination with Mysticism and what is often considered to be his anticipation of the Romanticism unfolding around him.[2] Nonetheless, the difficulty of placing William Blake in any one chronological stage of art history is perhaps the distinction that best defines him. Once considered "mad" for his "single-mindedness" (he lived and died in poverty), Blake is highly regarded today for his expressiveness and creativity, and the philosophical vision that underlies his work. As he himself once indicated, "The imagination is not a State: it is the Human existence itself."

William Blake (1757-1827) by Thomas Phillips (1770-1845), 1807. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Life

Youth

Blake was born in 28a Broad Street, Golden Square, London, to Catherine Wright (Armitage) and James Blake.[3] He was one of five children (an older brother had died in infancy). James Blake, a hosier, had never attended school, being educated at home by his mother. [4] The Blakes were Dissenters, and are believed to have belonged to the Moravian sect. The Bible was an early and profound influence on Blake, and would remain a source of inspiration throughout his life.

From a young age Blake claimed to have seen visions. The earliest instance occurred at the age of about eight or ten in Peckham Rye, London, when he reported seeing a tree filled with angels "bespangling every bough like stars." According to Blake's Victorian biographer Gilchrist, he returned home to report his vision, but only escaped being beaten by his father through the intervention of his mother.

Though all the evidence suggests that his parents were largely supportive, his mother seems to have been especially so, and several of Blake's early drawings and poems decorated the walls of her chamber. On another occasion, Blake watched haymakers at work, and thought he saw angelic figures walking among them. It is possible that other visions occurred before these incidents: in later life, his wife Catherine would recall the time he saw God's head "put to the window". The vision, Catherine reminded her husband, "set you ascreaming". [5]

Blake began engraving copies of drawings of Greek antiquities purchased for him by his father (a further indication of the support his parents lent their son), a practice that was then preferred to actual drawing. Within these drawings Blake found his first exposure to classical forms, through the work of Raphael, Michelangelo, Marten Heemskerk and Albrecht D�rer. (Blake Record, 422) His parents knew enough of his headstrong temperament that he was not sent to school but was instead enrolled in drawing classes. He read avidly on subjects of his own choosing. During this period, Blake was also making explorations into poetry; his early work displays knowledge of Ben Jonson and Edmund Spenser.

Apprenticeship to Basire

On 4 August 1772, Blake became apprenticed to engraver James Basire of Great Queen Street, for the term of seven years. At the end of this period, at the age of 21, he was to become a professional engraver.

Basire seems to have been a kind master to Blake: there is no record of any serious disagreement between the two during the period of Blake's apprenticeship. However, Ackroyd's biography notes that Blake was later to add Basire's name to a list of artistic adversaries—and then crossed it out.(43, Blake, Peter Ackroyd, Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995) This aside, Basire's style of engraving copied images from the Gothic churches in London (it is possible that this task was set in order to break up a quarrel between Blake and James Parker, his fellow apprentice), and his experiences in Westminster Abbey contributed to the formation of his artistic style and ideas; the Abbey of his day was decorated with suits of armour, painted funeral effigies and varicolored waxworks. Ackroyd notes that "the most immediate [impression] would have been of faded brightness and colour".(44, Blake, Ackroyd) In the long afternoons Blake spent sketching in the Abbey, he was occasionally interrupted by the boys of Westminster School, one of whom "tormented" Blake so much one afternoon that he knocked the boy off a scaffold to the ground, "upon which he fell with terrific Violence". Blake beheld more visions in the Abbey, of a great procession of monks and priests, while he heard "the chant of plain-song and chorale".

The Royal Academy

The archetype of the Creator is a familiar image in his work. Here, Blake depicts his demiurgic figure Urizen stooped in prayer, contemplating the world he has forged. The Song of Los is the third in a series of illuminated books painted by Blake and his wife, collectively known as the Continental Prophecies. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 1779, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy in Old Somerset House, near the Strand. While the terms of his study required no payment, he was expected to supply his own materials throughout the six-year period. There, he rebelled against what he regarded as the unfinished style of fashionable painters such as Peter Paul Rubens, championed by the school's first president, Joshua Reynolds. Over time, Blake came to detest Reynolds' attitude toward art, especially his pursuit of "general truth" and "general beauty". Reynolds wrote in his Discourses that the "disposition to abstractions, to generalizing and classification, is the great glory of the human mind"; Blake responded, in marginalia to his personal copy, that "To Generalize is to be an Idiot; To Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit". [6] Blake also disliked Reynolds' apparent humility, which he held to be a form of hypocrisy. Against Reynolds' fashionable oil painting, Blake preferred the Classical precision of his early influences, Michelangelo and Raphael.

In July 1780, Blake was walking towards Basire's shop in Great Queen Street when he was swept up by a rampaging mob that stormed Newgate Prison in London. Many among the mob were wearing blue cockades on their caps, to symbolise solidarity with the insurrection in the American colonies. They attacked the prison gates with shovels and pickaxes, set the building ablaze, and released the prisoners inside. Blake was reportedly in the front rank of the mob during this attack; most biographers believe he accompanied the crowd impulsively.

These riots, in response to a parliamentary bill designed to advance Roman Catholicism, later came to be known as the Gordon Riots; they provoked a flurry of legislation from the government of King George III, as well as the creation of the first police force.

Marriage and Early Career

Blake's "Newton" is a demonstration of his opposition to the "single-vision" of scientific materialism: the great philosopher-scientist is isolated in the depths of the ocean, his eyes (only one of which is visible) fixed on the compasses with which he draws on a scroll. He seems almost at one with the rocks upon which he sits. (1795)

In 1782 Blake met John Flaxman, who was to become his patron, and Catherine Boucher, who was to become his wife. At the time, Blake was recovering from a relationship that had culminated in a refusal of his marriage proposal. Telling Catherine and her parents the story, she expressed her sympathy, whereupon Blake asked her "Do you pity me?" To Catherine's affirmative response he himself responded "Then I love you." Blake married Catherine – who was five years his junior – on 18 August 1782 in St. Mary's Church, Battersea. An illiterate, Catherine signed her wedding contract with an 'X'. Later, in addition to teaching Catherine to read and write, Blake trained her as an engraver; throughout his life she would prove an invaluable aide to him, helping to print his illuminated works and maintaining his spirits throughout numerous misfortunes.

At this time, George Cumberland—one of the founders of the National Gallery—became an admirer of Blake's work. Blake's first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was published around 1783. After his father's death, William and his brother Robert opened a print shop in 1784, and began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson. At Johnson's house he met some of the leading intellectual dissidents of the time in England, including Joseph Priestley, scientist; Richard Price, philosopher; John Henry Fuseli, painter, with whom he became friends; Mary Wollstonecraft, an early feminist; and Thomas Paine, American revolutionary. Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the American and French revolution and wore a red liberty cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror in the French revolution.

Mary Wollstonecraft became a close friend, and Blake illustrated her Original Stories from Real Life (1788). They shared views on sexual equality and the institution of marriage. In 1793's Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the right of women to complete self-fulfillment.

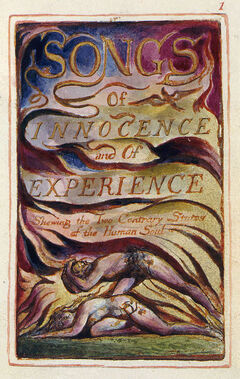

Relief Etching

In 1788, at the age of 31, Blake began to experiment with relief etching, a method he would use to produce most of his books of poems. The process is also referred to as illuminated printing, and final products as illuminated books or prints. Illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium. Illustrations could appear alongside words in the manner of earlier illuminated manuscripts. He then etched the plates in acid in order to dissolve away the untreated copper and leave the design standing. The pages printed from these plates then had to be hand-colored in water colors and stitched together to make up a volume. Blake used illuminated printing for most of his well-known works, including Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and Jerusalem.

By most accounts, Blake claimed to have learned this technique from his brother Robert, who had died in 1787 and appeared to Blake in visions.

Later life and career

Blake's "A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows"

Blake's marriage to Catherine remained a close and devoted one until his death. There were early problems, however, such as Catherine's illiteracy and the couple's failure to produce children. At one point, in accordance with the beliefs of the Swedenborgian Society, Blake suggested bringing in a concubine. Catherine was distressed at the idea, and Blake promptly withdrew it.

Around the year 1800 Blake moved to a cottage at Felpham in Sussex (now West Sussex) to take up a job illustrating the works of William Hayley, a poet. It was in this cottage that Blake wrote Milton: a Poem (published between 1805 and 1808). Over time, Blake came to resent his new patron, coming to believe that Hayley was not paying as well as he could afford to pay.

Blake returned to London in 1802 and began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804–1820). He was introduced by George Cumberland to a young artist named John Linnell. Through Linnell he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients. This group shared Blake's rejection of modern trends and his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. At the age of 65 Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job. These works were later admired by John Ruskin, who compared Blake favourably to Rembrandt.

Blake abhorred slavery and believed in racial and sexual equality. Several of his poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: "As all men are alike (tho' infinitely various)". He retained an active interest in social and political events for all his life, but was often forced to resort to cloaking social idealism and political statements in Protestant mystical allegory.

He rejected all forms of imposed authority; indeed, he was charged with assault and uttering seditious and treasonable expressions against the King in 1803, though he later was cleared in the Chichester assizes of the charges. The charges were brought by a soldier after Blake had bodily removed him from his garden, apparently exclaiming, "Damn the king. The soldiers are all slaves."[7] According to a report in the Sussex county paper, "the invented character of (the evidence) was ... so obvious that an acquittal resulted." [8].

Blake's views on what he saw as oppression and restriction of rightful freedom extended to the Church. He himself was a follower of Unitarian philosophy. His spiritual beliefs are evidenced in Songs of Experience (in 1794), in which he shows his own distinction between the Old Testament God, whose restrictions he rejected, and the New Testament God (Jesus Christ), whom he saw as a positive influence.

Later in his life Blake began to sell a great number of his works, particularly his Bible illustrations, to Thomas Butts, a patron who saw Blake more as a friend than a man whose work held artistic merit; this was typical of the opinions held of Blake throughout his life.

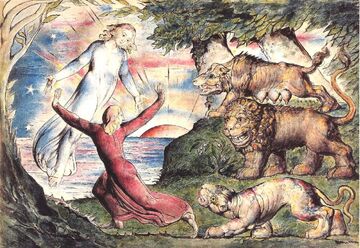

Dante's Inferno

illustration to Inferno, Canto I, ll.1-90 by William Blake. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The commission for Dante's Inferno came to Blake in 1826 through Linnell, with the ultimate aim of producing a series of engravings. However, Blake's death in 1827 would cut short the enterprise, and only a handful of the watercolours were completed, with only seven of the engravings arriving at proof form. Even so, they have evinced praise; for instance, the Cambridge Guide to William Blake says of them:

- '[T]he Dante watercolors are among Blake's richest achievements, engaging fully with the problem of illustrating a poem of this complexity. The mastery of watercolour has reached an even higher level than before, and is used to extraordinary effect in differentiating the atmosphere of the three states of being in the poem'.[9]

Blake's illustrations of the poem are not merely accompanying works, but rather seem to critically revise, or furnish commentary on, certain spiritual or moral aspects of the text. In illustrating Paradise Lost, for instance, Blake seemed intent on revising Milton's focus on Satan as the central figure of the epic; for example, in Satan Watching the Endearments of Adam and Eve (1808) Satan occupies an isolated position at the picture's top, with Adam and Eve centered below. As if to emphasise the effects of the juxtaposition, Blake has shown Adam and Eve caught in an embrace, whereas Satan may only onanistically caress the serpent, whose identity he is close to assuming.

In this instance, because the project was never completed, Blake's intent may itself be obscured. Some indicators, however, bolster the impression that Blake's illustrations in their totality would themselves take issue with the text they accompany: in the margin of Homer Bearing the Sword, and His Companions, Blake notes, "Every thing in Dantes Comedia shews That for Tyrannical Purposes he has made This World the Foundation of All & the Goddess Nature & not the Holy Ghost". Blake seems to dissent from Dante's admiration of the poetic works of the ancient Greeks, and from the apparent glee with which Dante allots punishments in Hell (as evidenced by the grim humour of the cantos).

At the same time, Blake shared Dante's distrust of materialism and the corruptive nature of power, and clearly relished the opportunity to represent the atmosphere and imagery of Dante's work pictorially. Even as he seemed to near death, Blake's central preoccupation was his feverish work on the illustrations to Dante's Inferno; he is said to have spent one of the very last shillings he possessed on a pencil to continue sketching.(Blake Records, 341)

Blake's death

Monument near Blake's unmarked grave in London. Photo by Fin Fahey, 2006. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

On the day of his death, Blake worked relentlessly on his Dante series. Eventually, it is reported, he ceased working and turned to his wife, who was in tears by his bedside. Beholding her, Blake is said to have cried, "Stay Kate! Keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait – for you have ever been an angel to me." Having completed this portrait (now lost), Blake laid down his tools and began to sing hymns and verses.(Ackroyd, Blake, 389) At six that evening, after promising his wife that he would be with her always, Blake died. Gilchrist reports that a female lodger in the same house, present at his expiration, said "I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel."(Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, London, 1863, 405) George Richmond gives the following account of Blake's death in a letter to Samuel Palmer:

- He died ... in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that Country he had all His life wished to see & expressed Himself Happy, hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ - Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten'd and he burst out Singing of the things he saw in Heaven. (Grigson, Samuel Palmer, p. 38)

Catherine paid for Blake's funeral with money lent to her by Linnell. He was buried five days after his death – on the eve of his forty-fifth wedding anniversary – at Dissenter's burial ground in Bunhill Fields, where his parents were also interred. Present at the ceremonies were Catherine, Edward Calvert, George Richmond, Frederick Tatham and John Linnell.

Following Blake's death, Catherine moved into Tatham's house as a housekeeper. During this period, she believed she was regularly visited by Blake, despite his having died. She continued selling his illuminated works and paintings, but would entertain no business transaction without first "consulting Mr. Blake".(Ackroyd, Blake, 390) On the day of her own death, in October 1831, she was as calm and cheerful as her husband, and called out to him "as if he were only in the next room, to say she was coming to him, and it would not be long now."(Blake Records, p. 410)

Upon her death, Blake's manuscripts were inherited by Frederick Tatham, who is rumored to have burned several of them in a fit of religious ardor. Tatham had become an Irvingite, one of the many fundamentalist movements of the 19th century, and was severely opposed to any work that smacked of blasphemy.[10]

Writing

Critical introduction

by J. Comyns Carr

The poetry of Blake holds a unique position in the history of English literature. Its extraordinary independence of contemporary fashion in verse, and its intuitive sympathy with the taste of a later generation, would alone suffice to give a peculiar interest to the study of the poet’s career. Nor is this interest in any way diminished by a knowledge of Blake’s singular and strongly marked individuality. Indeed, it is scarcely possible to do justice to the great qualities of his imagination, or to make due allowance for its startling defects, unless the exercise of the poetic gift is considered in relation to the other faculties of his mind.

He appealed to the world in the double capacity of poet and painter; and such was the peculiar nature of his endowment and the particular method of his work, that it is difficult to measure the value of his literary genius without some reference to his achievements in design. For it is not merely that he practised the two arts simultaneously, but that he chose to combine them after a fashion of his own. An engraver by profession and training, he began at a very early age to employ his technical knowledge in the invention of a wholly original system of literary publication. With the exception of the Poetical Sketches, issued in the ordinary form through the kindly help of friends, nearly all of Blake’s poems were given to the world in a fantastic dress of his own devising. He became in a special sense his own printer and his own publisher. The typography of his poems and the pictorial illustration by which they were accompanied were blended in a single scheme of ornamental design, and from the engraved plate upon which this design was executed by the artist’s own hand copies were struck off in numbers more than sufficient to satisfy the modest demands of his admirers.

This peculiar process of publication cannot of course be held to affect Blake’s claims as a poet. It bears a more obvious relation to those powers of a purely artistic kind which are not here in question; but its employment by him is nevertheless well deserving of remark in this place, because it indicates a certain quality of mind that deeply affected his poetic individuality. That happy mingling and confusion of text and ornament which give such a charm to Songs of Innocence was the symbol of a strongly marked intellectual tendency that afterwards received a morbid development.

Blake has been called mad, and within certain well-defined limits the charge must, we think, be admitted. He possessed only in the most imperfect and rudimentary form the faculty which distinguishes the functions of art and literature; and when his imagination was exercised upon any but the simplest material, his logical powers became altogether unequal to the labour of logical and consequent expression. That this failure arose rather from morbid excess and excitement of visionary power than from any abnormal defect of intellectual energy is sufficiently indicated by the facts of his career. For while his hold over the abstract symbols of language grew gradually feebler, his powers of pictorial imagery became correspondingly vigorous and intense. The artistic faculty in Blake strengthened and developed with advancing life, and he produced no surer or more satisfying example of his powers than the series of illustrations to the Book of Job, executed when he was already an old man.

Indeed if Blake had never committed himself to literature we should scarcely be aware of the morbid tendency of his mind. It is only in turning from his design to his verse that we are forced to recognise the imperfect balance of his faculties: nor could we rightly understand the strange limitation of his poetical powers without constant reference to this diseased activity of the artistic sense. For there is a large portion of Blake’s verse which is not infected at all with the suspicion of insanity, and it seems at first sight almost inexplicable that a writer who has produced some of the simplest and sweetest lyrics in the language should also have left behind him a confused mass of writings such as no man can hope to decipher. All that can be done for these so-called Prophetic Books has been accomplished by Mr. Swinburne, in his sympathetic study of the poet’s work; but although Mr. Swinburne rightly asserts the power that is displayed in them, his eloquent commentary does not substantially change the ordinary judgment of their confused and inconsequent character. The defects of such work are too grave for any kind of serious vindication to be really possible, and if Blake had produced nothing more or nothing better, his claims to rank among English poets could not be successfully maintained.

But these defects, although they are in their nature incurable, are not altogether incapable of explanation. For it cannot be questioned by any one who has seriously attempted to decipher these ‘prophetic’ writings, that to Blake himself the ordinary modes of intellectual expression had become charged with something of mysterious and special meaning. Words were no longer mere abstract symbols: they had assumed to his imagination the force of individual images. As they passed into his work they lost the stamp of ordinary currency and became impressed with a device of his own coinage, vivid and eloquent to him, but strange to all the world beside. To Blake’s mind, in short, these prophetic writings doubtless formed a series of distinct and coherent pictures; but without the key that he alone possessed, they must ever remain a chaos through which not even the most wary guide can hope to find a path.

Putting aside the prophetic books, the quantity of verse which Blake has left behind him is by no means large. His lyrical poems have been collected in a small volume edited by Mr. W. M. Rossetti, and the contents of this volume are found to be mainly derived from the Poetical Sketches and the Songs of Innocence and Experience. It is to these essays of his youth and early manhood that we must look for the true sources of his fame. The Poetical Sketches, begun when the author was only twelve years of age, and finished when he was no more than twenty, must assuredly be reckoned among the most extraordinary examples of youthful production; and it is profoundly characteristic of the man and his particular cast of mind that many of these boyish poems are among the best that Blake at any time produced. For his was a nature that owed little to development or experience.

The perfect innocence of his spirit, as it kept him safe from the taint of the world, also rendered him incapable of receiving that enlargement of sympathy and deepening of emotion which others differently constituted may gain from contact with actual life. His imagination was not of the kind that could deal with the complex problems of human passion; he retained to the end of his days the happy ignorance as well as the freshness of childhood: and it is therefore perhaps less wonderful in his case than it would be in the case of a poet of richer and more varied humanity that he should be able to display at once and in early youth the full measure of his powers.

But this acknowledgment of the inherent limitation of Blake’s poetic gift leads us by a natural process to a clearer recognition of its great qualities. His detachment from the ordinary currents of practical thought left to his mind an unspoiled and delightful simplicity which has perhaps never been matched in English poetry. The childlike beauty of his poems is entirely free from the awkward lisp of wisdom that condescends. It is always unconscious and always unstrained, and even the simplicity of a poet like Wordsworth must often seem by comparison to be tinged with a didactic spirit. Blake’s verse has indeed, both as regards intellectual invention and executive skill, a kind of unpremeditated charm that forces comparison with the things of inanimate life. Where he is successful his work has the fresh perfume and perfect grace of a flower, and at all times there is the air of careless growth that belongs to the shapes of outward nature.

And yet this quality of simplicity is constantly associated with an unusual power of rendering the most subtle effects of beauty. In the actual processes of his art Blake could command the utmost refinement and delicacy of style. He possessed in a rare degree the secret by which the loveliness of a scene can be arrested and registered in a line of verse, and he often displays a faultless choice of language and the finest sense of poetic melody.

We have said already that he worked in absolute independence of the accepted models of his time. This is strictly true: but it would be absurd therefore to assume that he laboured without any models at all. Blake’s isolation, if we look to the character of the man, is indeed less extraordinary than it would otherwise appear. He did not mingle in the concerns of life in such a way as to expose him to the dangers of being unduly swayed by the caprices of fashion. His was a world of his own creating, and to his vivid imagination the poets of an earlier generation would seem as near as the versifiers of his own day.

That he should have chosen from the past those models whose example was most needed in order to infuse a new life into English poetry proves of course the justice of his poetic instinct. In fixing upon the great writers of the Elizabethan age he anticipated, as we have already observed, the taste of a succeeding generation, and it is only to be regretted that he did not absolutely confine himself to these nobler models of style. Unfortunately however his own intellectual tendency towards mysticism, found only too ready encouragement in the prophetic vagueness of the Ossianic verse, and we may fairly trace a part at least of Blake’s obscurer manner to this source.[11]

Recognition

Ten of his poems ("To the Muses", "To Spring", "Song", "Reeds of Innocence", "The Little Black Boy", "Hear the Voice," "The Tiger", "Cradle Song", "Night", and "Love's Secret") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[12]

Blake is now recognised as a saint in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.

The Blake Prize for Religious Art was established in his honour in Australia in 1949.

On 24 November 1957 a bronze bust of Blake by Sir Jacob Epstein was unveiled in Poet' Corner, Westminster Abbey.[13]

Legacy

Blake may have played a critical role in the modern Western World's conception of imagination. His belief that humanity could overcome the limitations of its five senses is perhaps Blake's greatest legacy: "If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite."(The Marriage of Heaven and Hell) While his perspective was once perceived as merely aberrant, it now seems to have been incorporated into the modern definition of the term.

His reference to "the doors of perception" resonated demonstrably in the literature and music of the 20th century, as both Jim Morrison's band The Doors and Aldous Huxley's book The Doors of Perception pay homage to Blake's sentiment.

Publications

Poetry

- Poetical Sketches. London: privately printed, 1783

- facsimile. London: William Griggs, 1890.

- There is No Natural Religion (series a and b). London: Printed by William Blake, [1788?]

- (facsimile eition). (2 volumes), London: William Blake Trust, 1971.

- All Religions are One.(London: Printed by William Blake, [1788?]

- facsimile. London: William Blake Trust, 1970.

- Songs of Innocence. London: Printed by William Blake, 1789

- Songs of Innocence and of Experience. London: Printed by William Blake, 1794

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1955.

- The Book of Thel. London: Printed by William Blake, 1789

- facsimile London: William Blake Trust, 1965.

- The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. London: Printed by William Blake, [1793?]

- facsimile. London: William Blake Trust, 1960.

- Visions of the Daughters of Albion. London: Printed by William Blake, 1793

- facsimile. London: William Blake Trust, 1959.

- For Children: The Gates of Paradise. London: Printed by William Blake, 1793

- revised and enlarged as For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise. London: Printed by William Blake, [1818?]

- facsimile. London: William Blake Trust, 1968.

- America: A prophecy. Lambeth, UK: Printed by William Blake, 1793

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1963.

- Europe. Lambeth, UK: Printed by William Blake, 1794

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1969.

- The First Book of Urizen. Lambeth, UK: Printed by William Blake, 1794

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1975.

- The Song of Los. Lambeth, UK: Printed by William Blake, 1795

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1975.

- The Book of Los. Lambeth, UK: Printed by William Blake, 1795

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1975.

- The Book of Ahania. Lambeth, UK: Printed by William Blake, 1795

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1973.

- Milton. London: Printed by William Blake, 1804 [1808?]

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1967.

- Jerusalem. London: Printed by William Blake, 1804 [1820?]

- facsimile, London: William Blake Trust, 1951.

- The Poems of Willliam Blake. London: Basil Montagu Pickering, 1874.

- The Poems, with specimens of the prose writings, of William Blake (prefatory note by Joseph Skipsey). London: Walter Scott, 1885.[14]

- The Poetical Works of William Blake: A new and verbatim text (prefatory notes by Joseph Sampson). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1905.[15]

- The Poetical Works of William Blake (edited by Edwin J. Ellis). (2 volumes), London: Chatto & Windus, 1906.[16] Volume I, Volume 2.

- The Poetical works of William Blake (edited by William Michael Rossetti). London: G. Bell, 1914.[17]

- Selections from the Symbolical Poems of William Blake (edited by F.E. Pierce). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1915.[18]

Illustration

- Edward Young, The Complaint, and The Consolation; or Night Thoughts (illustrated by Blake). London: R. Edwards, 1797.

- William Hayley, The Life and Posthumous Writings of William Cowper, Esqr. (3 volumes, includes plates engraved by Blake). Chichester: Printed by J. Seagrave for J. Johnson, 1803 [1804].

- Robert Blair, The Grave, A Poem (illustrated by twelve Etchings Executed by Louis Schiavonetti, From the Original Inventions of William Blake). London: Cromek, 1808.

- facsimile, in Robert Blair's The Grave Illustrated by William Blake. A Study with a Facsimile (edited by Robert N. Essick and Milton D. Paley). London: Scolar Press, 1982).

- A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures, Poetical and Historical Inventions. Painted by William Blake in Water Colours, being the Ancient Method of Fresco Painting Restored: and Drawings .... London: Printed by D.N. Shury, 1809.

- Illustrations of the Book of Job, in Twenty-One Plates, Invented and Engraved by William Blake. London: Printed by William Blake, 1826

- facsimiles: The Illustrations of the Book of Job (edited by Lawrance Binyon and Geoffrey Keynes. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1935

- and in S. Foster Damon, Blake's Job: William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job. Providence: Brown University Press, 1966.

- Blake's Illustrations of Dante. Seven Plates, designed and engraved by W. Blake. London, 1838.

Reproductions

- Illustrations to Young's Night Thoughts Done in Water-Colour by William Blake (edited by Geoffrey Keynes). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927).

- Albert S. Roe, Blake's Illustrations to the Divine Comedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953.

- Geoffrey Keynes, Engravings by William Blake. Dublin: E. Walker, 1956.

- William Blake's Illustrations of the Bible (edited by Geoffrey Keynes). London: William Blake Trust, 1957.

- William Wells and Elizabeth Johnston, William Blake's "Heads of the Poets". Manchester: City of Manchester Art Gallery, 1969.

- Irene Taylor, Blake's Illustrations to the Poems of Gray. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971.

- William Blake's Water Colour Designs for the Poems of Thomas Gray. London: William Blake Trust, 1972.

- Iain Bain, David Chambers, and Andrew Wilton, The Wood Engravings of William Blake for Thornton's Virgil. London: British Museum Publications, 1977.

- Pamela Dunbar, William Blake's Illustrations to the Poetry of Milton. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

- William Blake's Designs for Edward Young's Night Thoughts (edited by John Grant, Edward Rose, Michael Tolley, and David Erdman). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

- Milton Klonsky, Blake's Dante. New York: Harmony Books, 1980.

- Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Manuscripts

- An Island in the Moon [written 1784?]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Tiriel [written 1789?]. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- The Notebooks of William Blake [written circa 1793-1818] (edited by David Erdman and Donald Moore). London: Oxford University Press, 1973.

- Vala, or The Four Zoas [written circa 1796-1807]. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Pickering Manuscript [written after 1807]. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1972.

Collected editions

- The Works of William Blake (edited by Edwin John Ellis & William Butler Yeats). (3 volumes), London: Bernard Quaritch, 1893.[19] Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- The Writings of William Blake (3 volumes, edited by Geoffrey Keynes). London: Oxford University Press, 1925

- revised as The Complete Writings of William Blake. London: Oxford University Press, 1957; second revision, 1966.

- Prose and Poems (edited by Floyd Dell). Girard, KS: Haldeman-Julius (Little Blue Book 677), 1925..[20]

- The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (edited by David Erdman). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965; revised, 1982.

- The Illuminated Blake (annotated by David Erdman). Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1974.

- William Blake's Writings (2 volumes, edited by G.E. Bentley, Jr.). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978.

Letters

- The Letters of William Blake (edited by Archibald G.B. Russell). London: Methuen, 1906; New York: Scribner's, 1906.[21]

- Letters from William Blake to Thomas Butts 1800-1803 (facsimile, edited by Geoffrey Keynes). London: Oxford University Press, 1926.

- The Letters of William Blake (third edition, revised and amplified, edited by Geofffrey Keynes). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[22]

Poems by William Blake

- Ah! Sunflower

- And did those feet in ancient time

- Auguries of Innocence

- The Chimney-Sweeper

- The Echoing Green

- The Lamb

- The Little Black Boy

- A Poison Tree

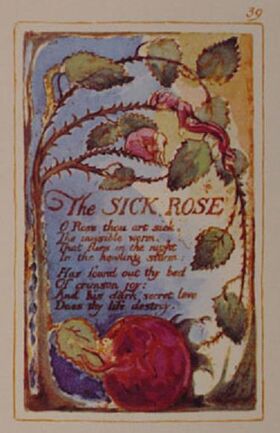

- The Sick Rose

- The Tiger

- To Autumn

- To Spring

- To Summer

- To Winter

See also

References

- Peter Ackroyd (1995). Blake. Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 1-85619-278-4.

- Donald Ault (1974). Visionary Physics: Blake's Response to Newton. University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-03225-6.

- G.E. Bentley Jr. (2001). The Stranger From Paradise: A Biography of William Blake. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08939-2.

- Jacob Bronowski (1972). William Blake and the Age of Revolution. Routledge and K. Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7277-5 (hardcover) ISBN 0-7100-7278-3 (pbk.)

- ――― (1967). William Blake, 1757-1827; a man without a mask. Haskell House Publishers.

- G.K. Chesterton (1920s). William Blake. House of Stratus ISBN 0-7551-0032-8.

- S. Foster Damon (1979). A Blake Dictionary. Shambhala. ISBN 0-394-73688-5.

- David V. Erdman (1977). Blake: Prophet Against Empire: A Poet's Interpretation of the History of His Own Times. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-486-26719-9.

- Irving Fiske (1951). "Bernard Shaw's Debt to William Blake." (Shaw Society)

- Northrop Frye (1947). Fearful Symmetry. Princeton Univ Press. ISBN 0-691-06165-3.

- Alexander Gilchrist, Life and Works of William Blake, (second edition, London, 1880)

- James King (1991). William Blake: His Life. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-07572-3.

- Dr. Malkin (1806). A Father's Memories of his Child.

- Peter Marshall (1988). William Blake: Visionary Anarchist ISBN 090038477

- W.J.T. Mitchell (1978). Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-691-01402-7.

- Victor N. Paananens (1996). William Blake. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-7053-4.

- George Anthony Rosso Jr. (1993). Blake's Prophetic Workshop: A Study of The Four Zoas. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8387-5240-3.

- Sheila A. Spector (2001). "Wonders Divine": the development of Blake's Kabbalistic myth, (Bucknell UP)

- Algernon Swinburne, William Blake: A Critical Essay, (London, 1868)

- E.P. Thompson (1993). Witness against the Beast. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22515-9.

- W. M. Rosetti (editor), Poetical Works of William Blake, (London, 1874)

- A. G. B. Russell (1912). Engravings of William Blake.

- Basil de S�lincourt, William Blake, (London, 1909)

- Joseph Viscomi (1993). Blake and the Idea of the Book, (Princeton UP). ISBN 0-691-06962-X.

- David Weir (2003). Brahma in the West: William Blake and the Oriental Rennaissance, (SUNY Press)

- Jason Whittaker (1999). William Blake and the Myths of Britain, (Macmillan)

- W.B. Yeats (1903). Ideas of Good and Evil. Contains essays.

Notes

- ↑ Jones, Jonathan (2005-04-25). "Blake's heaven". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/critic/feature/0,1169,1469584,00.html.

- ↑ Kazin, Alfred (1997). "An Introduction to William Blake". http://www.multimedialibrary.com/Articles/kazin/alfredblake.asp. Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- ↑ G.E. Bentley, William Blake, Britannica.com, Encyclopædia Britannica. Web, June 6, 2015.

- ↑ Raine, Kathleen (1970). World of Art: William Blake. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20107-2.

- ↑ Bentley, Gerald (1969). Blake Record. Oxford. pp. p543. ISBN 0-415-13441-2.

- ↑ Erdman, David V. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (2nd edition ed.). pp. p641. ISBN 0-385-15213-2.

- ↑ "The Gothic Life of William Blake: 1757-1827". Lilith Gallery of Toronto. http://www.lilithgallery.com/articles/williamblake1.html.

- ↑ Lucas, E.V. (1904). Highways and byways in Sussex. Macmillan. ASIN B-0008-5GBS-C.

- ↑ David Bindman, "Blake as a Painter" in The Cambridge Guide to William Blake, Morris Eaves (ed.), Cambridge, 2003, p. 106. Print.

- ↑ Ackroyd, Blake, p. 391

- ↑ from J. Comyns Carr, "Critical Introduction: William Blake (1757-1827)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Feb. 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Alphabetical list of authors: Addison, Joseph to Brome, Alexander. Arthur Quiller-Couch, editor, Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919). Bartleby.com, Web, May 15, 2012.

- ↑ William Blake, People, History, Westminster Abbey. Web, July 11, 2016.

- ↑ The Poems, with specimens of the prose writings, of William Blake (1885), Internet Archive. July 7, 2013.

- ↑ The Poetical Works of William Blake: A new and verbatim text (1905), Internet Archive. July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Search results = au:Edwin John Ellis, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Aug. 11, 2013.

- ↑ The Poetical works of William Blake (1914), Internet Archive. July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Selections from the Symbolical Poems of William Blake (1915), Internet Archive. July 7, 2013.

- ↑ The Works of William Blake (1893), Internet Archive. Web, July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Search results = au:Floyd Dell, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, June 7, 2015.

- ↑ The Letters of William Blake (1906), Internet Archive. Web, July 7, 2013.

- ↑ William Blake 1757-1827, Poetry Foundation, Web, Aug. 9, 2012.

External links

Template:Sister

- Poems

- "The Ecchoing Green"

- Blake's season poems: ("To Summer", "To Spring", "To Winter," "To Autumn").

- William Blake in the Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1900 ("To the Muses", "Song", "Reeds of Innocence", "The Little Black Boy", "Hear the Voice," "The Tiger", "Cradle Song", "Night", and "Love's Secret").

- William Blake in the Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse: "The Everlasting Gospel", "The Divine Image", "Broken Love", " The Crystal Cabinet", "Auguries of Innocence", "To Thomas Butts", from "Milton", from "Jerusalem"

- William Blake 1757-1827 at the Poetry Foundation

- William Blake (1757-1827) at English Poetry 1579-1830 (profile & 4 poems)

- Blake in The English Poets: An anthology:

- Extracts from Poetical Sketches: To the Evening Star, Song: ‘How sweet I roamed from field to field’, Song: ‘My silks and fine array’, Song: ‘Memory, hither come’, Mad Song, To the Muses

- Extracts from Songs of Innocence: Introduction, The Lamb, Night

- Extracts from Songs of Experience: Ah, Sunflower, The Tiger, The Angel

- William Blake profile & 24 poems at the Academy of American Poets

- Selected Poetry of William Blake (1757-1827) (45 poems) at Representative Poetry Online.

- William Blake at PoemHunter (138 poems)

- William Blake at Poetry Nook (379 poems)

- Blue Neon Alley - Directory and Poems

- Poetry Archive: 170 poems of William Blake at sanjeev.net.

- Blake: The Poetical Works at Bartleby.com

- Books

- The Songs of Innocence and The Songs of Experience by William Blake

- Contents, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (edited by David V. Erdman)

- Works by William Blake at Project Gutenberg

- Blake Digital Text Project

- William Blake: The complete works Official website.

- Audio / video

- Art

- Paintings of William Blake

- An Archive of an Exhibit of his Work at the National Gallery of Victoria

- Introduction to The Drawings and Engravings of William Blake, by Laurence Binyon at www.the3graces.info

- About

- William Blake in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- William Blake at NNDB

- William Blake at Spartacus Educational.

- A sixth form English lit perspective

- Blake, Willliam (1757-1827) in the Dictionary of National Biography

- William Blake in the Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- The William Blake Archive Official website.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

| This page uses content from Wikinfo . The original article was at Wikinfo:William Blake. The list of authors can be seen in the (view authors). page history. The text of this Wikinfo article is available under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license. |

|