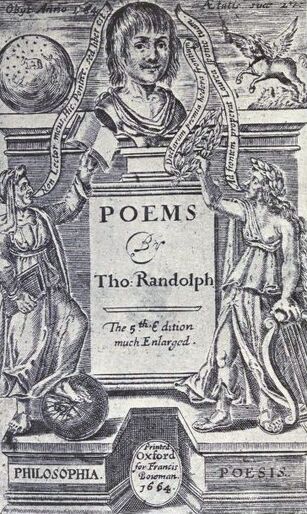

Thomas Randolph (1605-1635), Poems, and Amyntas, 1917. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Thomas Randolph (15 June 1605 - March 1635) was an English poet and dramatist.

Life[]

Overview[]

Randolph, educated at Westminster School and Cambridge, was a friend of Ben Jonson, and led a wild life in London. He wrote 6 plays, including The Jealous Lovers, Amyntas, and The Muses' Looking-glass, and some poems. He was a scholar as well as a wit, and his plays are full of learning and condensed thought in a style somewhat cold and hard.[1]

Youth[]

Randolph was the 2nd son of William Randolph of Hamsey, near Lewes, Sussex, and afterwards of Little Houghton, Northamptonshire, by his 1st wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas Smith of Newnham-cum-Badby, near Daventry, Northamptonshire. His father was steward to Edward, lord Zouch.[2]

Thomas was born at Newnham-cum-Badby in the house of his mother's father; a drawing of it appears in Baker's Northamptonshire (i. 261). He was baptized on 15 June 1605. He showed literary leanings as a child, and at the age of 9 or 10 wrote in verse the "History of the Incarnation of our Saviour," the autograph copy of which was preserved in Anthony à Wood's day.[2]

He was educated at Westminster School as a king's scholar, and was elected in 1623 to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he matriculated on 8 July 1624. James Duport, who was his junior by a year, was an admiring friend at both school and college, and subsequently commemorated his literary powers (Musæ Subsecivæ, 1696, pp. 469–70). Randolph graduated with a B.A. in January 1627-8, and was admitted a minor fellow 22 September 1629, and a major fellow 23 March 1631-2. He earned an M.A. in 1632.[2]

While an undergraduate Randolph was fired with the ambition of making the acquaintance of Ben Jonson and other leaders of London literary society. According to a contemporary anecdote of somewhat doubtful authenticity, he shyly made his way on a visit to London into the room in the Devil Tavern, near Temple Bar, where Ben Jonson was entertaining his friends. The party noticed his entrance, and challenged him "to call for his quart of sack." But he had spent all his money, and in an improvised stanza confessed that he could only drink with them at their expense. Jonson is said to have sympathised with him in his embarrassment, and to have "ever after called him his son."[3]

He acknowledged Jonson's kindness in a charming "gratulatory to Master Ben Johnson for his adopting of him to be his son," and gave further expression to his admiration for his master in 2 other poems, entitled respectively "An Answer to Master Ben Jonson's Ode to persuade him not to leave the Stage" and in "An Eclogue to Master Jonson."[3]

Career[]

After he had taken his degree in 1628, his visits to London grew more frequent, and his literary patrons or friends soon included, besides Jonson, Thomas Bancroft, James Shirley the dramatist, Owen Feltham, Sir Aston Cokain, and Sir Kenelm Digby. But until 1632 his time was mainly spent in Cambridge. According to his own account, while he "contented liv'd by Cham's fair stream," he was a diligent student of Aristotle (Poems, ed. Hazlitt, 609–10).[3]

He became famous in the university for his ingenuity as a writer of English and Latin verse, and was especially energetic in organizing dramatic performances by the students of pieces of his own composition. In 1630 he produced his 1st publication, Aristippus, or the Joviall Philosopher. Presented in a priuate Shew. To which is added the Conceited Pedler (London, for Robert Allot, 1630, 4to; other editions, 1631 and 1635).[3]

In 1632 there was acted with great success before Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria, at Cambridge, by the students of Randolph's college (Trinity), the Jealous Lovers, a comedy loosely following classical models (cf. Masson, Milton, i. 251–4). When published at the Cambridge University Press in the same year, it was respectfully dedicated to Thomas Comber, vice-chancellor of the university and master of Trinity. To the book Randolph prefixed verses addressed to his friends Sir Kenelm Digby, Sir Christopher (afterwards Viscount) Hatton, Anthony Stafford, and others, while Edward Hide, Duport, Francis Meres, and his brother Robert were among those who complimented him on his success as a playwright.[3]

Other literary works which he produced under academic influences were Latin poems in the university collections celebrating the birth of Princess Mary in 1631, and Charles I's return from Scotland in 1633. A mock-heroic "oratio prævaricatoria," delivered before the senate in 1632, was 1st printed in Hazlitt's collected edition of his works.[3]

After 1632 Randolph indulged with increasing ardor in the dissipations of London literary life. In 2 poems he recounted the loss of a finger in an affray which followed a festive meeting (cf. Ashmole MS. 38, No. 34, for a bantering reply by Mr. Hemmings to 1 of the poems). Thomas Bancroft lamented that "he drank too greedily of the Muse's spring."[3]

Creditors harassed him, and his health failed. He was attacked by smallpox, and, after staying with his father in 1634 at Little Houghton, Northamptonshire, he paid a visit to his friend William Stafford of Blatherwick. There he died in March 1634-5, within 3 months of his 30th birthday, and on the 17th he was buried in the vault of the Stafford family, in an aisle adjoining the parish church.[3]

Robert Randolph[]

The younger brother, Robert (1613–1671), who posthumously edited Thomas Randolph's Poems, was also educated at Westminster as a king's scholar, and was elected in 1629 to Christ Church, Oxford, where he matriculated on 24 Feb. 1631–2, aged 19. He earned a B.A. on 1 June 1633, and an M.A. (as Randall) on 3 May 1636. Wood describes him as "an eminent poet." He took holy orders, and was vicar successively of Barnetby and of Donnington. He was buried in Donnington church on 7 July 1671 (Wood, Fasti, i. 430; Foster, Alumni Oxon.; Welsh, Alumni Westmonast. p. 901).[4]

Writing[]

Randolph achieved a wide reputation in his own day, and was classed by his contemporaries among "the most pregnant wits of his age." Fertile in imagination, he could on occasion express himself with rare power and beauty. But his promise, as might be expected from his irregular life and premature death, was greater than his performance. Phillips, in his Theatrum Poetarum,’ 1675, wrote: "The quick conceit and clear poetic fancy discovered in his extant poems seems to promise something extraordinary from him, had not his indulgence to the too liberal converse with the multitude of his applauders drawn him to such an immoderate way of living as, in all probability, shortened his days."[4]

Aristippus (1630), which is in prose interspersed with verse, is a witty satire in dramatic form on university education, and a rollicking defence of tippling. The phrase in one of Randolph's verses — "blithe, buxom, and debonair" — was borrowed by Milton in his "L'Allegro." The Conceited Pedler is a monologue which would not have discredited Autolycus.[3]

The Jealous Lovers (1632), an admirable comedy in blank verse, is Randolph's most ambitious effort.[3]

In 1638 appeared a posthumous volume, Poems, with the Muses' Looking-Glasse and Amyntas (Oxford, by Leonard Lichfield, for Francis Bowman, 4to). A copy of it, bound with Milton's newly issued "Comus," was forwarded to Sir Henry Wotton by Milton's and Wotton's "common friend Mr. R.," who is variously identified with Randolph's brother Robert, the editor, or with Francis Rous, the Bodleian librarian. Wotton, in a letter to Milton, complimenting him on ‘Comus’ (printed in Milton's Poems, 1643), assigns the binding up of Randolph's Poems with "Comus" to a bookseller's hope that the accessory (i.e. ‘Comus’) ‘might help out the principal.’ To the volume were prefixed an elegy in English and some verses in Latin by Randolph's brother Robert, as well as elegies by Edmund Gayton, Owen Feltham, and the poet's brother-in-law, Richard West. The poems include translations from Horace and Claudian, and a few Latin verses on Bacon's death, on his friend Shirley's Grateful Servant, and the like; but the majority are original and in English.[3]

Separate title-pages introduce The Muses' Looking Glasse and Amyntas. The Muses' Looking Glasse by T.R. resembled in general design the earlier Aristippus. Sir Aston Cokain, in commendatory verses, called it "the Entertainment," and it doubtless was acted at Cambridge.[3]

In the opening scene in the Blackfriars Theatre 2 puritans, who are strongly prejudiced against the theatre, are accosted by a 3rd character, Roscius, and the latter undertakes to convert them from the view that plays can only serve an immoral purpose. There follow a disconnected series of witty and effective dialogues between characters representing various vices and virtues; the dialogues seek to show that practicable virtue is a mean between 2 extremes. In the contrasted portrayal of men's humors Ben Jonson's influence is plainly discernible.[3]

The piece was long popular. Jeremy Collier wrote a preface for a new edition of 1706. Some scenes were acted at Covent Garden on 14 March 1748 and 9 March 1749, when Mrs. Ward and Ryan appeared in the cast (GENEST, iv. 250–1, 280). The ‘Mirrour,’ an altered version, was published in 1758.[3]

"Amyntas, or the Fatal Dowry," a "Pastoral acted before the King and Queen at Whitehall," is adapted from the poems of Guarini and Tasso.[3]

The Poems, with their appendices and some additions, including ‘The Jealous Lovers,’ reappeared in 1640, again at Oxford. A title-page, with a bust of Randolph, was engraved by William Marshall. A 3rd edition is dated London, 1643; a 4th, which adds the ‘Aristippus’ and ‘The Conceited Pedler,’ London, 1652; a 5th, ‘with several additions corrected and amended,’ at Oxford in 1664; and a 6th (misprinted the ‘5th’) at Oxford in 1668.[3]

All the pieces named were reissued by W.C. Hazlitt in 1875, together with a few other short poems, and another play traditionally assigned to Randolph, Πλουτοφθαλμία Πλουτογαμία, a pleasant comedie entituled Hey for Honesty, Down with Knavery. Translated out of Aristophanes his Plutus by Tho. Randolph. Augmented and published by F. J[aques?], London, 1651, 4to. This is a very free adaptation of Aristophanes, and contains so many allusions to events subsequent to Randolph's death as to render his responsibility for it improbable. Charles Lamb included selections from it in his Specimens. Hazlitt is doubtless accurate in assigning to Randolph 2 poems printed together in 1642 as by "Thomas Randall," viz. "Commendation of a Pot of good Ale" and "The Battle between the Norfolk Cock and Cock of Wisbech."[4]

Hazlitt did not include a witty but indelicate Latin comedy called Cornelianum Dolium, comedia lepidissima, auctore T.R. ingeniosissimo hujus ævi Heliconio (London, 1638, 12mo), which is traditionally assigned to Randolph. There is a curious frontispiece by William Marshall. Mr. Crossley more probably attributed it to Richard Brathwaite (Notes and Queries, 2nd ser. xii. 341–342). Another claimant to the authorship is Thomas Riley of Trinity College, Cambridge, a friend of Randolph, to whom the latter inscribes a poem before The Jealous Lovers; but even if Riley's claim be admitted, it is quite possible that Brathwaite had some share in it as editor. On 29 June 1660 a comedy by "Thomas Randall," called The Prodigal Scholar, was licensed for publication by the Stationers' Company, but nothing further is known of it.[4]

Critical introduction[]

by Edmund Gosse

It seems probable that in the premature death of Randolph, English literature underwent a very heavy loss. He died unexpectedly when he was only 29, leaving behind him a mass of writing at once very imperfect and very promising. The patronage of Ben Jonson, it would seem, rather than any very special bias to the stage, led him to undertake dramatic composition, and though he left six plays behind him, it is by no means certain that he would have ended as a dramatist.

His knowledge of stage requirements is very small indeed; it would be impossible to revive any of his pieces on the modern boards on account of the essential uncouthness of the movement, the length of the soliloquies, and the thinness of the plot. His 3 best dramas are distinguished by a vigorous directness and buoyancy of language, and by frequent passages of admirable rhetorical quality, but they are hardly plays at all, in the ordinary sense. His master-piece, The Muses’ Looking Glass, is a moral essay in a series of dialogues, happily set in a framework of comedy; The Jealous Lovers is full, indeed, of ridiculous stratagems and brisk humorous transitions, but it has no sanity of plot; while Amyntas is a beautiful holiday dream, aery and picturesque, and ringing with peals of faery laughter, but not a play that any mortal company of actors could rehearse.

Intellect and imagination Randolph possessed in full measure, but as he does not seem to have been born to excel in play-writing or in song-writing, and as he died too early to set his own mark on literature, we are left to speculate down what groove such brilliant and energetic gifts as his would finally have proceeded. Had he lived longer his massive intelligence might have made him a dangerous rival or a master to Dryden, and as he shows no inclination towards the French manner of poetry, he might have delayed or altogether warded off the influx of the classical taste. He showed no precocity of genius; he was gradually gathering his singing-robes about him, having already studied much, yet having still much to learn. There is no poet whose works so tempt the critic to ask, ‘what was the next step in his development?’ He died just too soon to impress his name on history.

Besides his dramas, Randolph composed a considerable number of lyrics and occasional poems. Of these the beautiful "Ode to Master Anthony Stafford to Hasten Him into the Country" is the best. In this he is more free and graceful in his Latinism than usual. He was a deep student of the Roman poets, and most of his non-dramatic pieces are exercises, performed in a hard though stately style, after Ovid, Martial and Claudian. It cannot be said that these have much charm, except to the technical student of poetry, who observes, with interest, the zeal and energy with which Randolph prepared himself for triumphs which were never to be executed.

In pastoral poetry he had attained more ease than in any other, and some of his idyls are excellently performed. The glowing verses entitled "A Pastoral Courtship" remind the reader of the twenty-seventh idyl of Theocritus, on which they were probably modelled. "The Cotswold Eclogue", which originally appeared in a very curious book entitled Annalia Dubrensia, 1636, is one of the best pastorals which we possess in English.

But in reviewing the fragments of the work of Randolph, the critic is ever confronted by the imperfection of his growing talent, the insufficiency of what exists to account for the personal weight that Randolph carried in his lifetime, and for the intense regret felt at his early death. Had he lived he might have bridged over, with a strong popular poetry, the abyss between the old romantic and the new didactic school, for he had a little of the spirit of each. As it is, he holds a better place in English literature than Dryden, or Gray, or Massinger would have held had they died before they were thirty.[5]

Recognition[]

His friend Sir Christopher, lord Hatton, erected a marble monument in the church to his memory, with an English inscription in verse by Peter Hausted.[3]

2 of his poems, "A Devout Lover" and "An Ode to Master Anthony Stafford", were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[6] [7]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Poems; with The Muses Looking-Glasse, and Amyntas. Oxford: Leonard Lichfield for Francis Bowman, 1638.

- Poems; and Amyntas (edited by John Jay Parry). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1917.

- Poems (edited by George Thorn-Drury). London, F. Etchells & H. Macdonald, 1929.

Plays[]

- The Jealous Lovers: A comedie. Cambridge, UK: Printers to the Universitie of Cambridge, for Rich. Ireland, 1632.

- The Fickle Shepherdess. London: William Turner, 1703.

- The Drinking Academy: A play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930.

Collected editions[]

- Poetical and Dramatic Works (edited by William Carew Hazlitt). London: Reeves & Turner, 1875; New York: B. Blom, 1968. Volume I

The Milkmaid's Epithalamium, by Thomas Randolph

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[8]

See also[]

References[]

Lee, Sidney (1896) "Randolph, Thomas (1605-1635)" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 47 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 280-282. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 22, 2018.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Randolph, Thomas," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 314. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 21, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Lee, 280.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 Lee, 281.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Lee, 282.

- ↑ from Edmund W. Gosse, "Critical Introduction: Thomas Randolph (1605–1635)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Feb. 13, 2016.

- ↑ "A Devout Lover," Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 12, 2012.

- ↑ "An Ode to Master Anthony Stafford," Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 12, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Thomas Randolphe 1635, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Feb. 13, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- Randolph in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900: "A Devout Lover," "An Ode to Master Anthony Stafford, to hasten him into the country".

- Thomas Randolph at the Poetry Foundation

- Randolph, Thomas (1605-1635) ("An Ode to Master Anthony Stafford, to Hasten him into the Country," "On Sixe Cambridge Lasses Bathinge Themselfes by Queenes Colledge on the 25th of June at Night and Espied by a Scholer") at Representative Poetry Online

- Thomas Randolph (1605-1635) info & 3 poems at English Poetry, 1579-1830

- Randolph in The English Poets: An anthology: "Ode to Master Anthony Stafford," Extract from "The Cotswold Eclogue", Extract from "A Pastoral Courtship', "To Ben Jonson"

- Thomas Randolph at PoemHunter (6 poems)

- Thomas Randolph at Poetry Nook (91 poems)

- Audio / video

- Thomas Randolph poems at YouTube

- About

- Thomas Randolph in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Thomas Randolph in the Cambridge History of English and American Literature.

- Randolph, Thomas (poet)" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Randolph, Thomas (1605-1635)

|