Richard Brautigan (1935-1984). Drawing by Olivier Dalmon. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| Richard Brautigan | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Richard Gary Brautigan 30, 1935 Tacoma, Washington, United States |

| Died |

circa 14, 1984 (aged 49) Bolinas, California, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist/Poet |

| Nationality |

|

| Genres |

Fabulation Black comedy Parody Postmodernism |

| Notable work(s) | Trout Fishing in America (1967) |

|

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Richard Gary Brautigan (January 30, 1935 - September 14, 1984) was a 20th century American poet, novelist, and short story writer. His work often employs black comedy, parody, and satire. He is best known for his 1967 novel Trout Fishing in America.

Life[]

Youth[]

Brautigan was born in Tacoma, Washington, the only child of Bernard Frederick "Ben" Brautigan, Jr. (July 29, 1908 - May 27, 1994) a factory worker and laborer, and Lulu Mary "Mary Lou" Keho (April 7, 1911 - September 24, 2005), a waitress. In May 1934, 8 months prior to his birth, Bernard and Mary Lou separated. Brautigan said that he met his biological father only twice, though after Brautigan's death, Bernard was said to be unaware that Richard was his child, saying "He's got the same last name, but why would they wait 45 to 50 years to tell me I've got a son?"[1]

In 1938, Brautigan and his mother began cohabiting with a man named Arthur Martin Titland. The couple produced a daughter named Barbara Ann, born on May 1, 1939 in Tacoma. Brautigan claimed that he had a very traumatic experience when his mother left him alone with his 2-year-old sister in a motel room in Great Falls, Montana, not knowing the whereabouts of his mother until she returned two days later.

On January 20, 1943, Mary Lou married a fry cook named Robert Geoffrey Porterfield. The couple produced a daughter named Sandra Jean, born April 1, 1945 in Tacoma. Mary Lou told Brautigan that Porterfield was his biological father, and Brautigan began using Richard Gary Porterfield as his name. Mary Lou separated from Porterfield in 1946, and married William David Folston, Sr., on June 12, 1950. The couple produced a son named William David, Jr., born on December 19, 1950 in Eugene. Folston was recalled as being a violent alcoholic, whom Richard had seen subjecting his mother to domestic abuse.

Brautigan was raised in poverty; he told his daughter stories of his mother sifting rat feces from their supply of flour to make flour-and-water pancakes.[2] Because of Brautigan's impoverished childhood, he and his family found it difficult to obtain food, and on some occasions they did not eat for days. He lived with his family on welfare and moved about the Pacific Northwest for nine years before the family settled in Eugene, Oregon in August 1944. Many of Brautigan's childhood experiences were included in the poems and stories that he wrote from as early as the age of 12. His novel So the Wind Won't Blow It All Away is loosely based on childhood experiences including an incident where Brautigan accidentally shot the brother of a close friend in the ear, injuring him only slightly.

On September 12, 1950, Brautigan enrolled at South Eugene High School, having graduated from Woodrow Wilson Junior High School. He was a writer for his high school newspaper South Eugene High School News. He also played on his school's basketball team, standing 6 feet 4 inches tall (1.93 m) by the time of his graduation. On December 19, 1952, Brautigan's 1st published poem, "The Light," appeared in the South Eugene High School newspaper. Brautigan graduated with honors from South Eugene High School on June 9, 1953. Following graduation, he moved in with his best friend Peter Webster, and Peter's mother Edna Webster became Brautigan's surrogate mother. According to several accounts Brautigan stayed with Webster for about a year before leaving for San Francisco for the first time in August 1954. He returned to Oregon several times, apparently for lack of money.[3]

On December 14, 1955, Brautigan was arrested for throwing a rock through a police-station window, supposedly in order to be sent to prison and fed. He was arrested for disorderly conduct and fined $25. He was then committed to the Oregon State Hospital on December 24, 1955, after police noticed patterns of erratic behavior.

At the Oregon State Hospital Brautigan was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and clinical depression, and was treated with electroconvulsive therapy 12 times(Citation needed). While institutionalized, he began writing The God of the Martians, a manuscript of 20 very short chapters totaling 600 words. The manuscript was sent to at least two editors but was rejected by both, and remains unpublished.[4] (A copy of the manuscript was recently discovered with the papers of the last of these editors, Harry Hooton.)

On February 19, 1956, Brautigan was released from hospital and briefly lived with his mother, stepfather, and siblings in Eugene, Oregon. He then left for San Francisco, where he would spend most of the rest of his life except for periods in Tokyo and Montana.[3]

Career[]

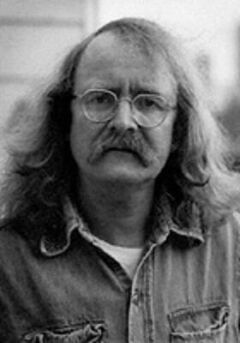

Richard Brautigan. Courtesy PoemHunter.

In San Francisco Brautigan sought to establish himself as a writer. He was known for handing out his poetry on the streets and performing at poetry clubs. Brautigan's first published book was The Return of the Rivers (1958), a single poem, followed by two collections of poetry: The Galilee Hitch-Hiker (1958) and Lay the Marble Tea (1959). During the 1960s Brautigan became involved in the burgeoning San Francisco counterculture scene, often appearing as a performance-poet at concerts and participating in the various activities of The Diggers. Brautigan was also a writer for Change, an underground newspaper created by Ron Loewinsohn.

In the summer of 1961 Brautigan went camping with his wife and his daughter [see Personal Life section] in southern Idaho. While camping he completed the novels A Confederate General From Big Sur and Trout Fishing in America. A Confederate General from Big Sur was his 1st published novel and met with little critical or commercial success. But when Trout Fishing in America was published in 1967, Brautigan was catapulted to international fame. Literary critics labeled him the writer most representative of the emerging countercultural youth-movement of the late 1960s, even though he was said to be contemptuous of hippies.[5] Trout Fishing in America has sold over 4 million copies worldwide.

During the 1960s Brautigan published 4 collections of poetry as well as another novel, In Watermelon Sugar (1968). In the spring of 1967 he was Poet-in-Residence at the California Institute of Technology. During this year, he published All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, a chapbook published by The Communication Company. It was printed in an edition of 1,500 copies and distributed for free. From late 1968 to February 1969, Brautigan recorded a spoken-word album for The Beatles' short-lived record-label, Zapple. The label was shut down by Allen Klein before the recording could be released, but it was eventually released in 1970 on Harvest Records as Listening to Richard Brautigan.[6]

In the 1970s Brautigan experimented with different literary genres. He published five novels (the first of which, The Abortion: An historical romance 1966, had been written in the mid-1960s) and a collection of short stories, Revenge of the Lawn (1971). "When the 1960s ended, he was the baby thrown out with the bath water," said his friend and fellow writer, Thomas McGuane. "He was a gentle, troubled, deeply odd guy." Generally dismissed by literary critics and increasingly abandoned by his readers, Brautigan's popularity waned throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. His work remained popular in Europe, however, as well as in Japan, where Brautigan visited several times.[7] To his critics, Brautigan was willfully naive. Lawrence Ferlinghetti said of him, "As an editor I was always waiting for Richard to grow up as a writer. It seems to me he was essentially a naïf, and I don't think he cultivated that childishness, I think it came naturally. It was like he was much more in tune with the trout in America than with people."[8]

Brautigan's writings are characterized by a remarkable and humorous imagination. The permeation of inventive metaphors lent even his prose-works the feeling of poetry. Evident also are themes of Zen Buddhism like the duality of the past and the future and the impermanence of the present. Zen Buddhism and elements of the Japanese culture can be found in his novel Sombrero Fallout: A Japanese Novel. Brautigan's last published work before his death was his novel So the Wind Won't Blow It All Away which was published in 1982, two years before his death.

Private life[]

On June 8, 1957, Brautigan married Virginia Dionne Alder in Reno, Nevada. The couple had one daughter together, Ianthe Elizabeth Brautigan, born on March 25, 1960 in San Francisco. Brautigan's alcoholism and depression became increasingly abusive[9] and Alder ended the relationship on December 24, 1962, though the divorce was not finalized until July 28, 1970. Brautigan continued to reside in San Francisco after the separation, while Alder settled in Manoa, Hawaii and became a feminist and an anti-Vietnam War activist.

Brautigan remarried on December 1, 1977, to the Japanese-born Akiko Yoshimura whom he met in July 1976 while living in Tokyo, Japan. The couple settled in Pine Creek, Park County, Montana for two years; Brautigan and Yoshimura were divorced in 1980.

Brautigan had a relationship with a San Francisco woman named Marcia Clay from 1981 to 1982. He also pursued a brief relationship with Janice Meissner, a woman from the North Beach community of San Francisco. Other relationships were with Marcia Pacaud, who appears on the cover of The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster; Valerie Estes, who appears on the cover of Listening to Richard Brautigan; and Sherry Vetter, who appears on the cover of Revenge of the Lawn.

Brautigan was an alcoholic throughout his adult life and suffered years of despair; according to his daughter, he often mentioned suicide over a period of more than a decade before ending his life.[2]

In 1984, at age 49, Richard Brautigan had recently moved to Bolinas, California, where he was living alone in a large, old house. He died of a self-inflicted .44 Magnum gunshot wound to the head. The exact date of his death is unknown, and his decomposed body was found by Robert Yench, a private investigator, on October 25, 1984. The body was found on the living room floor, in front of a large window that looked out over the Pacific Ocean. It is speculated that Brautigan may have ended his life over a month earlier, on September 14, 1984, after talking to former girlfriend Marcia Clay on the telephone. Brautigan was survived by his parents, both ex-wives, and his daughter Ianthe. He has one grandchild named Elizabeth, who was born about two years after his death.

Brautigan once wrote, "All of us have a place in history. Mine is clouds."[10]

Recognition[]

Brautigan's daughter, Ianthe Elizabeth Brautigan, describes her memories of her father in her book You Can't Catch Death (2000).

Also in a 1980 letter to Brautigan from W. P. Kinsella, Kinsella states that Brautigan is his greatest influence for writing and his favorite book is In Watermelon Sugar.

In March 1994, a teenager named Peter Eastman, Jr. from Carpinteria, California legally changed his name to Trout Fishing in America, and now teaches English at Waseda University in Japan.[11] At around the same time, National Public Radio reported on a young couple who had named their baby Trout Fishing in America.

There is a folk rock band called Trout Fishing in America,[12] and another called Watermelon Sugar,[13] which quotes the opening paragraph of that book on their home page. The industrial rock band Machines of Loving Grace took their name from a poem of Brautigan's. Indie rock songtress Neko Case has also admitted to basing her "Margaret vs. Pauline" from Fox Confessor Brings the Flood on the female characters of In Watemelon Sugar.

The Library for Unpublished Works envisioned by Brautigan in his novel The Abortion was housed at The Brautigan Library in Burlington, Vermont, until 1995 when it was moved to the nearby Fletcher Free Library where it remained until 2005. Although there were plans to move it to the Presidio branch of the San Francisco Public Library, these never materialised. However, an agreement was made between Brautigan's daughter Ianthe Brautigan and the Vancouver, Washington, Clark County Historical Museum to move The Brautigan Library to the museum in 2010.[14][15]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Return of the Rivers. Inferno Press, 1957.

- The Galilee Hitch-Hiker. White Rabbit Press, 1958.

- Lay the Marble Tea: Twenty-four poems. Carp Press, 1959.

- The Octopus Frontier. Carp Press, 1960.

- All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace. Communication Co., 1967.

- The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster. Four Seasons Foundation, 1968.

- Please Plant This Book (eight poems printed on separate seed packet envelopes). Graham Mackintosh, 1968.

- The San Francisco Weather Report. Unicorn Books, 1969.

- Rommel Drives on Deep Into Egypt. Delacorte, 1970.

- Loading Mercury with a Pitchfork. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976. ISBN 0-671-22263-5, ISBN 0-671-22271-6 pb

- June 30th, June 30th. Delacorte, 1978. ISBN 0-440-04295-X

- The Edna Webster Collection of Undiscovered Writings. 1999.[16] ISBN 0-395-97469-0

Novels[]

- A Confederate General From Big Sur (novel). Grove, 1964. ISBN 0-224-61923-3

- Trout Fishing in America (novel). Four Seasons Foundation, 1967. ISBN 0-395-50076-1

- In Watermelon Sugar (novel). Four Seasons Foundation, 1967. ISBN 0-440-34026-8

- Trout Fishing in America, The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster, In Watermelon Sugar. Delacorte, 1968.

- The Abortion: An historical romance, 1966. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971. ISBN 0-671-20872-1

- The Hawkline Monster: A gothic western. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974. ISBN 0-671-21809-3

- Willard and His Bowling Trophies: A perverse mystery. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975. ISBN 0-671-22065-9

- Sombrero Fallout: A Japanese novel. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976. ISBN 0-671-22331-3

- Dreaming of Babylon: A private eye novel, 1942. Delacorte, 1977. ISBN 0-440-02146-4

- The Tokyo-Montana Press. Delacorte, 1980.[17] ISBN 0-440-08770-8

- So The Wind Won't Blow It All Away. 1982.[16] ISBN 0-395-70674-2

- Revenge of the Lawn, The Abortion, So the Wind Won't Blow It All Away. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

- The God of the Martians (unpublished novel, written 1955-56).[16]

Short fiction[]

- Revenge of the Lawn: Stories, 1962-1970. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971.

Non-fiction[]

- An Unfortunate Woman: A journey. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000. ISBN 0-312-27710-5

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[18]

Audio/video[]

Love Poem Richard Brautigan

Richard Brautigan, " All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace" (HD)

- Listening to Richard Brautigan (LP). Hollywood, CA: Harvest, 1970.

- BBT'99: The Brautigan basement tapes (CD). Brautigan newsgroup, 2000.

- Trout Fishing in America (CD). Princeton, NJ: Recordings for the Blind & Dyslexic, 2009.

- The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster (CD). Princeton, NJ: Recordings for the Blind & Dyslexic, 2009.

- An Unfortunate Woman: A journey (CD). Ashland, OR: Blackstone Audio, 2016.

- So the Wind Won't Blow It All Away (CD). Ashland, OR: Blackstone Audio, 2016.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[19]

See also[]

References[]

- Chénetier Marc – ‘Richard Brautigan’, Metheun & Co, London, New York, 1983. ISBN 0-416-32960 (pbk)

- Clayton, John. ‘Richard Brautigan: The Politics of Woodstock’ New American Review, 11 (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1971) pp. 56 – 68.

- Critique: Studies in Modern Fiction, 16, 1 (Minneapolis, Minn., 1974) Richard Brautigan special issue.

- Loewinsohn, Ron. ‘After the (Mimeographed) Revolution’. Tri-Quarterly (Spring 1970), pp. 221 - 36.

- Malley, Terence. Richard Brautigan. Writers for the Seventies. New York: Warner Paperback Library, 1972

- Meltzer, David (ed.). In The San Francisco Poets, pp. 1-7, 293-7. New York: Ballintine, 1971

- Putz, Manfed. In The Story of Identity, pp. 105 – 29. Stuttgart: Metzler, 1979

- Schmitz, Neil. ‘Richard Brautigan and the Modern Pastoral’ Modern Fiction Studies (Spring 1973) pp. 109 – 25.

- Stevick, Philip. ‘Scherhezade Runs out of Plots, Goes on Talking, The King, Puzzled, Listens’. Tri-Quarterly (Winter 1973), pp. 332 – 62.

- Swigart, Rob. ‘Review of Still Life with Woodpecker by Tom Robbins and The Tokyo – Montana Express by Richard Brautigan’. American Book Review, 3, 3 (March – April 1981). P. 14.

- Tanner, Tony. In City of Words, pp. 393, 406-15. New York: Harper & Row, 1971.

Notes[]

- ↑ UPI news report, 27 October 1984, reproduced at http://www.brautigan.net/obituaries.html#bernard2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Brautigan, Ianthe: You Can't Catch Death: A Daughter's Memoir. St. Martin's Press, 2000. ISBN 1841950254.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 John F. Barber, Curator. "Biography". Brautigan Bibliography and Archive. http://www.brautigan.net/biography.html. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ http://www.brautigan.net/novels.html

- ↑ John F. Barber, Curator. "Memoirs". Brautigan Bibliography and Archive. http://www.brautigan.net/memoirs.html#wright. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ John F. Barber, Curator. "Recordings". Brautigan Bibliography and Archive. http://www.brautigan.net/recordings.html#listening. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ John F. Barber, Curator. "Biography: 1970s". Brautigan Bibliography and Archive. http://www.brautigan.net/chronology1970.html. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ Manso, Peter and Michael McClure. "Brautigan's Wake." Vanity Fair, May 1985: 62-68, 112-116.

- ↑ "Freedom?": Richard Brautigan's first wife, Virginia Aste, speaks in a new interview

- ↑ "Richard Brautigan 1935-1984". http://kerouacalley.com/brautigan.html. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ↑ Anne Saker (October 11, 2007). "Searching upstream: A writer goes fishing for the man who calls himself Trout Fishing in America". The Oregonian. http://www.oregonlive.com/oregonian/stories/index.ssf?/base/living/119197050984080.xml&coll=7. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ The Official Trout Fishing In America Web Site

- ↑ Watermelon Sugar :: News :: Indie Folk Duo :: Hypatia Kingsley and Louise Thompson Bendall

- ↑ http://www.brautigan.net/legacy.html#library

- ↑ O'Kelly, Kevin (September 27, 2004). "Unusual library may get new chapter". The Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/ae/books/articles/2004/09/27/unusual_library_may_get_new_chapter. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Richard Brautigan," Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Web, Aug. 12, 2012.

- ↑ There is some disagreement as how to classify The Tokyo-Montana Express. John Barber at brautigan.net classifies it as a collection of stories. The Brautigan Pages classifies it as a novel.

- ↑ Richard Brautigan 1935-1984, Poetry Foundation, Web, Aug. 12, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Richard Brautigan + audiobook, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center. Web, Sep. 27, 2016.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Gee, You’re So Beautiful That It’s Starting to Rain" at Poetry 180

- Richard Brautigan profile & 4 poems at the Academy of American Poets.

- Richard Brautigan 1935-1984 at the Poetry Foundation.

- Poems and quotes at the now defunct Kerouac Alley website

- Richard Brautigan at PoemHunter (62 poems)

- The Richard Brautigan Collection from poet Joanne Kyger at Granary Books

- Audio / video

- Books

- Richard Brautigan at Amazon.com

- Works by or about Richard Brautigan in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- About

- "Richard Brautigan" by John Cusatis in The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poets and Poetry, 2006

- Richard Brautigan by Jay Boyer in the Western Writers Series Digital Editions at Boise State University

- Brief critique on the life and legacy of Richard Brautigan

- Richard Brautigan at NNDB

- "The Brilliance of Richard Brautigan" at The Guardian

- "Brautigan Bibliography and Archive: A bio-bibliographical archive for Richard Brautigan, his life, and writings."

- Brautigan.net Unofficial website.

- The Brautigan Pages Unofficial website.

- Etc.

- "Finding Aid to the Richard Brautigan Papers, 1942-2003, (bulk 1958-1984)" (Collection number BANC MSS 87/173 c) University of California, Berkeley. Bancroft Library

- An interview with the memoirist Ianthe Brautigan on the creative process as well as memories of her father -- about-creativity.com March 31, 2008.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

| This page uses content from Wikinfo . The original article was at Wikinfo:Richard Brautigan. The list of authors can be seen in the (view authors). page history. The text of this Wikinfo article is available under the GNU Free Documentation License and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license. |

|