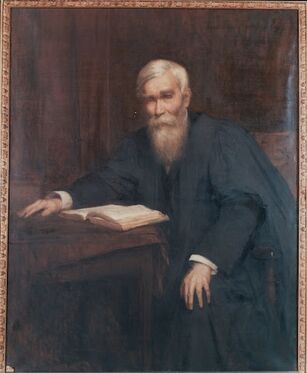

John Kells Ingram (1823-1907). Portrait by Sarah Henrietta Purser (1848-1943). Courtesy Google Arts and Culture.

John Kells Ingram (7 July 1823 - 1 May 1907) was an Irish poet and economist.

Life[]

Overview[]

Ingram was born in co. Donegal, Ireland, on 7 July 1823. Educated at Newry School and Trinity College, Dublin, he was elected a fellow of his college in 1846. He held the professorship of Oratory and English Literature in Dublin University from 1852 to 1866, when he became regius professor of Greek. In 1879 he was appointed librarian. Ingram was remarkable for his versatility. In his undergraduate days he had written the well-known poem “Who fears to speak of Ninety-eight?” and his Sonnets and other Poems (1900) reveal the poetic sense. He contributed many important papers to mathematical societies on geometrical analysis, and did much useful work in advancing the science of classical etymology, notably in his Greek and Latin Etymology in England, the Etymology of Liddell and Scott. His philosophical works include Outlines of the History of Religion (1900), Human Nature and Morals according to A. Comte (1901), Practical Morals (1904), and the Final Transition (1905). He contributed to the 9th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica an historical and biographical article on political economy, which was translated into nearly every European language. His History of Slavery and Serfdom was also written for the 9th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. He died in Dublin on 18 May 1907.[1]

Youth and education[]

Ingram was born at the rectory of Temple Came, co. Donegal, the eldest son of William Ingram, then curate of the parish, by his wife, Elizabeth (Cooke). Thomas Dunbar Ingram was his younger brother. The family was descended from Scottish Presbyterians, who settled in co. Down in the 17th century. Ingram's father, who was elected in 1790 a scholar of Trinity College, Dublin, died in 1829, and his 5 children were brought up by his widow, who survived till 22 Feb. 1884. Mother and children moved to Newry, and John and his brothers were educated at Dr. Lyons' school there.[2]

At the early age of 14 (13 Oct. 1837) Ingram matriculated at Trinity College, Dublin, winning a sizarship the next year, a scholarship in 1840, and a senior moderatorship in 1842. He graduated with a B.A. early in 1843.[2]

In his undergraduate days Ingram showed precocious promise alike as a mathematician and as a classical scholar. In December 1842 he helped to found the Dublin Philosophical Society, acting as its first secretary, and contributing to its early Transactions 11abstruse papers in geometry. He always said that the highest intellectual delight which he experienced in life was in pure geometry, and his geometrical papers won the praise of his teacher, James MacCullagh, the eminent mathematical professor of Trinity. But from youth upwards Ingram showed that intellectual versatility which made him well-nigh the most perfectly educated man of his age.[2]

Academic career[]

In 1844 Ingram failed in competition for a fellowship at Trinity College, but was consoled with the Madden prize. He was elected a fellow 2 years later, obtaining a dispensation from the obligation of taking holy orders. He had thought of the law as a profession, in case he failed to obtain the dispensation. At a later period, in 1852, he was admitted a student of the King's Inns, Dublin, and in 1854 of Lincoln's Lin. But after taking his fellowship he was actively associated with Trinity College in various capacities for 53 years.[3]

Ingram gave further results of geometrical inquiry in papers which he read to the Royal Irish Acedemy in the spring 1847 on "curves and surfaces of the second degree." At the same time he was extending his knowledge in many other directions, in classics, metaphysics, and economics. Although Carlyle met him as a young member of Trinity during his tour in Ireland in 1849, he only recognised him as author of the Repeal song, and described him as a "clever indignant kind of little fellow" who had become "wholly English, that is to say, Irish rational in sentiment" (Carlyle's Irish Journey, 1849 (1882), pp. 52, 56).[3]

In 1850 Ingram visited London for the first time, and also made a first tour up the Rhine to Switzerland. In London he then made the acquaintance of his lifelong friend, George Johnston Allman Other continental tours followed later.[3]

In 1852 Ingram received his earliest professorial appointment at Trinity, becoming Erasmus Smith professor of oratory. 3 years later the duty of giving instruction in English literature was attached to the chair. Thus Ingram was the earliest to give formal instruction in English literature in Dublin University, although no independent chair in that subject was instituted till 1867.[3]

A public lecture which he delivered in Dublin on Shakespeare in 1863 showed an original appreciation of the chronological study of the plays, and of the evidence of development in their versification (see The Afternoon Lectures on English Literature, Dublin, 1863, pp. 93-131; also ibid. 4th ser., 1867, pp. 47-94). A notable paper on the weak endings of Shakespeare, which, first read before a short-lived Dublin University Shakespeare Society, was revised for the New Shakspere Society's Transactions (1874, pt. 2), defined his views of Shakespearean prosody.[3]

In 1866 Ingram became regius professor of Greek at Dublin, a post which he held for 11 years. Although he made no large contribution to classical literature, he proved his fine scholarship, both Greek and Latin, in contributions — chiefly on etymology — to Hermathena, a scholarly periodical which was started at Trinity College in 1874 under his editorship. A sound textual critic, he had little sympathy with the art of emendation.[3]

In 1879 Ingram became librarian of Trinity College, and displayed an alert interest in the books and especially in the MSS. under his charge. He had already described to the Royal Irish Academy in 1858 a manuscript in the library of Roger Bacon's Opus Majus which supplied a 7th and hitherto overlooked part of the treatise (on moral philosophy). He also printed Two Collections of Medieval Moralised Tales (Dublin, 1882) from medieval Latin manuscripts in the Diocesan Library, Derry, as well as The Earliest English [fifteenth century] Translations of the "De Imitatione Christi" from a MS. in Trinity College library (1882) which he fully edited for the Early English Text Society in 1893.[3]

Ingram was also well versed in library management. Two years before becoming university librarian he had been elected a trustee of the National Library of Ireland, being re-elected annually until his death, and he played an active part in the organisation and development of that institution. When the Library Association met in Dublin in 1884, he was chosen president, and delivered an impressive address on the library of Trinity College.[3]

In 1881, on the death of the provost, Humphrey Lloyd, Ingram narrowly missed succeeding him. He became senior fellow in 1884, and in 1887 he ceased to be librarian on his appointment as senior lecturer.[3]

In 1898 he became vice-provost, and on resigning that position the next year he severed his long connection with Dublin university.[3]

Economics and philosophy[]

Throughout his academic career Ingram was active outside as well as inside the university. He always took a prominent part in the affairs of the Royal Irish Academy, serving as secretary of the council from 1860 to 1878, and while a vice-president in 1886 he presided, owing to the absence through illness of the president (Sir Samuel Ferguson), at the celebration of the centenary of the academy. He was president from 1892 to 1896.[4]

In 1886 Ingram became an additional commissioner for the publication of the Brehon Laws. In 1893 he was made a visitor of the Dublin Museum of Science and Art, and he aided in the foundation of Alexandra College for Women in 1866.[4]

Meanwhile economic science divided with religious speculation a large part of his intellectual energy. In economic science he made his widest fame. In 1847 he had helped to found the Dublin Statistical Society, which was largely suggested by the grave problems created by the great Irish famine; Archbishop Whately was the first president. Ingram took a foremost part in the society's discussions of economic questions. He was a member of the council till 1857, when he became vice-president, and was the secretary for the 3 years 1854-1856; he was president from 1878 to 1880.[4]

In an important paper which he prepared for the society in 1863 — "Considerations on the State of Ireland" — Ingram took an optimistic view of the growing rate of emigration from Ireland, but argued at the same time for reform of the land laws, and an amendment of the poor law on uniform lines throughout the United Kingdom. Wise and sympathetic study of poor law problems further appears in two papers, "The Organisation of Charity" (1875), and "The Boarding out of Pauper Children" (1876).[4]

In 1878, when the British Association met in Dublin, Ingram was elected president of the section of economic science and statistics, and delivered an introductory address on "The present position and prospects of political economy." Here he vindicated the true functions of economic science as an integral branch of sociology. His address was published in 1879 in both German and Danish translations.[4]

In 1880 he delivered to thor Trades Union Congress at Dublin another address on "Work and the Workman," in which he urged the need for workmen of increased material comfort and security, and of higher intellectual and moral attainments. This address was published next year in a French translation. From 1882 to 1898 he was a member of the Loan Fund Board of Ireland.[4]

Ingram's economic writings covered a wide range. To the 9th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica he contributed 16 articles on economists or economic topics. His most important contributions — on political economy (1885) and slavery (1887) — were each reprinted in a separate volume. The History of Political Economy (1888) traced the "development of economic thought in its relation with general philosophic ideas rather than an exhaustive account of economic literature." The book quickly obtained world-wide repute. Translations were published in German and Spanish (1890; 2nd German edit. 1906), in Polish and Russian (1896; 2nd edit. 1897), in Italian and Swedish (1892), in French (1893), (partly) in Czech (1895), in Japanese (1896), in Servian (1901), and again in French (1908).[4]

Ingram's History of Slavery and Serfdom (1895) was an amplification of the encyclopædia article. It was translated into German in 1905. He was also a contributor to Palgrave's Dictionary of Political Economy (1892-1899).[4]

Ingram's economic position was coloured by his early adoption of Comte's creed of positivism. His attention was first directed to Comte's views when he read the reference to them in John Stuart Mill's Logic soon after its publication in 1843. It was not till 1851 that he studied Comte's own exposition of his religion of humanity; he thereupon became a devoted adherent. In September 1855 he visited Comte in Paris (Comte's Correspondence, i. 335 ; ii. 186). To Comte's influence is attributable Ingram's treatment of economics as a part of sociology, and his conception of society as an organism and of the consensus of the functions of tho social system.[4]

Religious and political views[]

Though Ingram never concealed his religious opinions, he did not consider himself at liberty publicly to avow and defend them, so long as he retained his position in Trinity College. In 1900, the year after his retirement, when he was already 77, he published his Outlines of the History of Religion, in which he declared his positivist beliefs. In the same year there appeared his collected verse, Sonnets, and other poems, which was largely inspired by Comte's principles.[5]

Several other positivist works followed: Human Nature and Morals according to Auguste Comte (1901) ; Passages [translated] from the Letters of Auguste Comte (1901); Practical Morals: A treatise on Universal Education (1904), and The Final Transition: A sociological study (1905). Between 1904 and 1906 he contributed to the Positivist Review, and on its formation in 1903 he accepted a seat on the Comité Positiviste Occidental. Ingram sided with Richard Congreve in the internal differences of 1879 as to organisation within the positivist ranks.[5]

Despite his sympathy with the Celtic people of Ireland and their history, Ingram distrusted the Irish political leaders of his time. He attended the great unionist demonstration at Dublin in November 1887. In theory he judged separation to be the real solution of the Irish problem, but deemed the country unripe for any heroic change (cf. Sonnets, 1900).[5]

To all military aggression he was hostile. He strenuously opposed the South African war (1899-1902). One of his finest sonnets commemorated the death of Sir George Pomeroy Colley at the battle of Majuba Hill on 27 Feb. 1881. It formed a reply (in the Academy, 2 April 1881) to an elegiac sonnet by Archbishop Trench in Macmillan's Magazine of the same month. Ingram, while honouring Colley's valour, denounced as "foul oppression" the cause for which he fought.[5]

Private life[]

Ingram married on 23 July 1862 Madeline, daughter of James Johnston Clarke, D.L., of Largantogher Maghera, co. Londonderry.[5]

His wife died on 7 October 1889, leaving 4 sons and 2 daughters.[5]

Ingram died at his residence, 38 Upper Mount Street, Dublin, and was buried in Mount Jerome cemetery.[5]

Writing[]

After contributing verse and prose in boyhood to Newry newspapers, Ingram published 2 well-turned sonnets in the Dublin University Magazine for February 1840.[2]

His collected poetry, Sonnets, and other poems, was published in 1900.[6]

Many of Ingram's published sonnets are addressed to his wife, including 'Winged Thoughts,' which commemorates the death in South Africa, in 1895, of his 3rd son, Thomas Dunbar Ingram, 2 of whose own sonnets appear in the volume.[5]

In 1843 Ingram sprang into unlooked-for fame as a popular poet. On a sudden impulse he composed on an evening in Trinity in March 1843 the poem entitled "The Memory of the Dead," beginning "Who fears to speak of Ninety-eight?" It was printed in the Nation newspaper on 1 April anonymously, but Ingram's responsibility was at once an open secret. Though his view of Irish politics quickly underwent modification, the verses became and have remained the anthem of Irish nationalism. They were reprinted in The Spirit of the Nation in 1843 (with music in 1845); and were translated into admirable Latin alcaics by Professor R.Y. Tyrell in Kottabos (1870), and thrice subsequently into Irish. Ingram did not publicly claim the authorship till 1900, when he reprinted the poem in his collected verse.[2]

Recognition[]

Ingram was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy on 11 January 1847.[3]

The degree of D.Litt. was conferred on him in 1891. In 1893 he received the honorary degree of LL.D. from Glasgow University.[3]

His portrait, painted by Miss Sarah Purser, R.H.A., was presented by friends to the Royal Irish Academy on 22 February 1897.[5]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Sonnets, and other poems. London: A. & C. Black, 1900.

Novels[]

- Amelia Somers, the Orphan; or, The buried alive!. Boston: Wright's Steam Power Press, 1846.

- Love and Sorrow. Dublin: privately published, 1897.

Non-fiction[]

- On the 'Opus Majus' of Roger Bacon. Dublin: Dublin University Press, 1858.

- Considerations on the State of Ireland. Dublin: E. Ponsonby, 1864.

- The Present Position and Prospects of Political Economy. London: & Dublin: 1878.

- Work and the Workman: Being an address to the Trades' Union Congress, at their meeting in Dublin, 16th September, 1880. Dublin: R.D. Webb, 1880; London, Longmans / Dublin, Ponsonby, 1884; Dublin: Eason & Son, 1928.

- On Two Collections of Medieval Moralized Tales. Dublin: 1882.

- The Library of Trinity College Dublin. London: Chiswick Press, 1886.

- A History of Political Economy. London: A. & C. Black, 1888; New York: Macmillan, 1888; New York: A.M. Kelley, 1967; Cambridge, UK, & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- A History of Slavery and Serfdom. London: A. & C. Black, 1895.

- Auguste Comte and one of his Critics. [Dublin?]: [1897?]

- Outlines of the History of Religion. London: A. & C. Black, 1900.

- Human Nature and Morals According to Auguste Comte. London: A. & C. Black, 1901.

- Practical Morals: A treatise on universal education. London: A. & C. Black, 1904.

- The Final Transition: A sociological study. London: A. & C. Black, 1905.

Translated[]

- Passages from the Letters of Auguste Comte. London: 1901.

Edited[]

- The Earliest English Translation of the First Three Books of the 'De Imitatione Christi'. London: K. Paul Trench, Trubner, for the Early English Text Society, 1893

- also published as Middle English Translations of 'De Imitatione Christi'. Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint, 1973.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[6]

Willard Losinger Performs "The Memory of the Dead" by John Kells Ingram, with Charango Accompaniment

See also[]

References[]

Lee, Sidney, ed (1912). "Ingram, John Kells". Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement. 2. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 339-342. (DNB12). Wikisource, Web, Feb. 13, 2017.

Notes[]

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Ingram, John Kells". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 565-566. Wikisource, Web, Aug. 19, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 DNB12, 339.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 DNB12, 340.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 DNB12, 341.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 DNB12, 342.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Search results = au:John Kells Ingram, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Feb. 13, 2017.

External links[]

- Poems

- "The Memory of the Dead" in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895

- John Kells Ingram at Poetry Nook (66 poems)

- Books

- John Kells Ingram at Amazon.com

- About

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Dictionary of National Biography, 2nd supplement (edited by Sidney Lee). London: Smith, Elder, 1912. Original article is at: Ingram, John Kells

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at: Ingram, John Kells

|