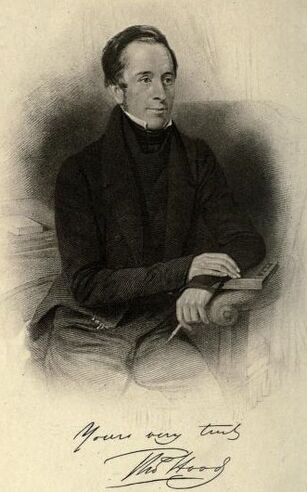

Thomas Hood (1799-1845). Engraving by William Holl, Jr. (1807-1871), after Thomas Lewis, from The Poems of Thomas Hood, 1897. Courtesy Internet Arthive.

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 - 3 May 1845) was an English poet and humorist.

Life[]

Overview[]

Hood was the son of a bookseller in London, where he was born. He was put into a mercantile office, but the confinement proving adverse to his health, he was sent to Dundee, where the family had connections, and where he obtained some literary employment. His health being restored, he returned to London, and entered the employment of an uncle as an engraver. Here he acquired an acquaintance with drawing, which he afterwards turned to account in illustrating his comic writings. After working for a short time on his own account he became, at the age of 22, sub-editor of the London Magazine, and made the acquaintance of many literary men, including De Quincey, Lamb, and Hazlitt. His first separate publication, Odes and Addresses to Great People, appeared in 1825, and had an immediate success. Thus encouraged he produced in the next year Whims and Oddities, and in 1829, he commenced The Comic Annual, which he continued for 9 years, and wrote in The Gem his striking poem, "Eugene Aram." Meanwhile he had married in 1824, a step which, though productive of the main happiness and comfort of his future life, could not be considered altogether prudent, as his health had begun to give way, and he had no means of support but his pen. Soon afterwards the failure of his publisher involved him in difficulties which, combined with his delicate health, made the remainder of his life a continual struggle. The years between 1834 and 1839 were the period of most acute difficulty, and for a part of this time he was obliged to live abroad. In 1840 friends came to his assistance, and he was able to return to England. His health was, however, quite broken down, but his industry never flagged. During the 5 years which remained to him he acted as editor of the New Monthly Magazine, and then of Hood's Monthly Magazine. In his last year a Government pension of £100 was granted to his wife. Among his other writings may be mentioned Tylney Hall, a novel which had little success, and Up the Rhine, in which he satirised the English tourist. Considering the circumstances of pressure under which he wrote, it is little wonder that much of his work was ephemeral and beneath his powers, but in his particular line of humour he is unique, while his serious poems are instinct with imagination and true pathos. A few of them, such as "The Song of the Shirt" and "The Bridge of Sighs," are perfect in their kind.[1]

Youth[]

Hood was born at 31 Poultry, London, the second son of Thomas Hood (died 1811), a Scotchman, who was at the time a partner in the bookselling firm of Vernor & Hood; the poet's mother was a sister of the engraver Sands.[2]

After receiving some education at private schools in London, Hood entered a merchant's counting-house there when about 13, but his health failed and he was sent to some of his father's relatives at Dundee to recover. He remained in Dundee from 1815 to 1818, and occupied himself in reading and sketching, and in writing for local newspapers.[2]

On returning to London he was articled to his uncle the engraver, and subsequently to Le Keux; but the confinement of the profession proved too trying for his delicate constitution, and he turned to literature.[3]

Early career[]

Taylor & Hessey, the publishers, old friends of his father, gave him in 1821 employment as an assistant sub-editor upon their London Magazine, to which he was a constant contributor until its transference to other hands in 1823. His contributions, chiefly in verse, comprise examples of nearly all the styles of composition in which he subsequently excelled. He became acquainted with most of the then brilliant staff of contributors, including De Quincey, Hazlitt, and Charles Lamb.[3]

In 1825 he published anonymously, in conjunction with John Hamilton Reynolds, Odes and Addresses to Great People, which no less a critic than Coleridge ascribed to Lamb. On 5 May 1825 he married Reynolds's sister Jane. Lamb's lines, "On an Infant dying as soon as born," were prompted by the death of their child.[3]

Hood's time was now entirely devoted to authorship. The two series of Whims and Oddities appeared respectively in 1826 and 1827, and were followed by the now entirely forgotten National Tales, novelettes somewhat in the manner of Boccaccio. The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies was published in 1827, and the dramatic romance of Lamia, first printed in 1852 in the appendix to vol. i. of Jerdan's Autobiography, was probably written about this time.[3]

In 1829 Hood became editor of the Gem, an annual which gave to light many remarkable productions (or at least productions of remarkable men, such as Tennyson). His own Eugene Aram's Dream was among them. In the same year he moved from Robert Street, Adelphi, to Winchmore Hill, where he spent 3 years. In 1832 he went to live at Wanstead. While there he had a hand in Reynolds's Gil Blas, and other dramatic pieces, which his son afterwards found it impossible to identify. The Comic Annual, commenced in 1830, was a more substantial undertaking, and met with the most favourable reception. While at Wanstead he wrote his novel, Tylney Hall (1834, 3 vols.), and his poem on the Epping Hunt.[3]

Later career[]

Towards the close of 1834 Hood met with heavy pecuniary misfortunes, the cause of which is obscurely stated; they appear to have been due to the failure of a publisher. Rejecting the temptation to shield himself by a declaration of insolvency, he yielded up all his property to his creditors. Temporarily provided for by advances made to him by publishers on the mortgage of his brain, he retired to the continent with a view to economy while clearing off the liabilities yet remaining. Upon his voyage to Holland (March 1835) he was overtaken by a terrible storm, the effects of which seriously impaired his already weakly constitution.[3]

He settled successively at Coblentz (1835-1837) and Ostend (1837-1840), continuing his annual, and writing Hood's Own (1838) and Up the Rhine, commenced in 1836 and published in 1839. Much of his correspondence during this period is preserved in the Memorials published by his children; its gaiety and spirit are remarkable indeed for a consumptive patient almost worn out by continual attacks of exhausting illness.[3]

In 1840 he returned to England, living successively at Camberwell and St. John's Wood, and began to write for the New Monthly Magazine, of which, on the death of Theodore Hook in August 1841, he became the editor. In it appeared "Miss Kilmansegg," perhaps his masterpiece in his own most characteristic style. Still greater success was attained by the "Song of the Shirt," published anonymously in the Christmas number of Punch for 1843.[3]

Final years[]

Hood, who could seldom agree with a publisher, retired from the editorship of the New Monthly Magazine at the end of 1843, and with a partner established Hood's Magazine in January 1844, an undertaking too great for his strength. In the same year he collected some of his recent pieces in a volume called Whimsicalities illustrated by Leech. But before Christmas 1844 he completely broke down, and from that date to his death never left his bed.[3]

The kindness of Sir Robert Peel soothed his last days by the bestowal of a pension of 100l., with remainder to his wife. The last production of Hood's pen, and not the least valuable, was a letter to the statesman on the estrangement between classes in modern society. He died on 3 May 1845 at Devonshire Lodge, Finchley Road, and was buried in Kensal Green cemetery.[3]

Writing[]

There were two sides to Hood's poetical character, either of which would have given him distinction; but his great and unique reputation rests upon the performances in which they appeared in combination. As a poet in the more conventional and restricted sense he was graceful, delicate, and tender, but not very powerful. As a humorist he was exuberant and endowed with a perfectly exceptional faculty of playing upon words.[3]

As a poet he is no unworthy disciple of Lamb and Hunt;[3] as a humorist he resembles Barham, with less affluence of grotesque invention, but with a pathos to which Barham was a stranger. In his 2 most famous poems, the "Song of the Shirt" and the "Bridge of Sighs," this pathos is almost detached from the humorous element in which it is commonly imbedded, and the result is two of the rarest achievements of contemporary verse — pieces equally attractive to the highest and the humblest, genuine Volkslieder of the 19th century.[4]

He is, however, most truly himself when the serious and the comic are inextricably combined, as in those masterpieces "Miss Kilmansegg" and the "Epistle to Rae Wilson." Here he stands alone, even though the association of poetry and humour is the general note of his literary work. As a man he was highly estimable; and the tragic necessity laid upon him of jesting for a livelihood while in the very grasp of death imparts a painful interest to his biography.[4]

Critical introduction[]

Since the issue in 1860 of the delightful Memorials of Thomas Hood by his son and daughter, both of whom are now dead, it has not been easy to dissociate the poet from the touching picture of him which those pages present. Nor indeed does literature often afford the spectacle of a heroism so smiling as that of the indefatigable manufacturer of Whims and Oddities, Comic Annuals, and the like,—pumping up ceaseless fun for a subsistence,—faultless in his relations of husband and father,—patient under sickness and ‘lack of pence’—and concluding, at last, that the life which to him, as to Pope, had been ‘a long disease,’ was still worth living, and the world he was leaving a beautiful one, ‘and not so bad, humanly speaking, even as people would make it out.’

Whether, under favourable circumstances, he would have produced more work of a high character is a question that it is scarcely profitable to discuss; but it is manifest that during his life-time the somewhat coarse-palated public welcomed most keenly not so much his best as his second-best. The ‘Tom Hood’ they cared for was not the delicate and fanciful author of the Plea of the Midsummer Fairies, but the Hood of Miss Kilmansegg and her Precious Leg,— the master of broad-grin and equivoque, the delightful parodist, the irrepressible and irresistible joker and Merry-Andrew. It is not to be denied that much of his work in this way is excellent of its kind, admirable for its genuine drollery and whim, having often at its core, moreover, that subtle sense of the lacrimæ rerum, which lends a piquancy of sadness and almost a quality of permanence to much of our modern jesting.

But the rest!— the larger part! Nothing except the record of his over-strained, over-burdened life can enable us to understand how the author of the Ode to Rae Wilson, the Lament for Chivalry, and the lines On a distant Prospect of Clapham Academy could ever have produced such mechanical and melancholy mirth as much of that which has been preserved appears to be. Yet his worst work is seldom without some point; it is better than the best of many others; and, with all its drawbacks, it is at least always pure. It should be remembered too that the fashions of fun pass away like other fashions.

It was fortunate, however, for his good fame that the public of his day could not wholly detain him in the jester’s domain. He was from the first, and remained throughout his life, a poet of distinct individuality and delicacy of note. Side by side with the fugitive puns and work-a-day witticisms, he found leisure to produce a number of pieces worthy of something more than mere ephemeral life. Such are Hero and Leander, the galloping anapæsts of Lycus the Centaur, and the beautiful petition to ‘all-devouring Time’ for Titania and her fragile following. In these, his earlier works, we may trace the influence of the Elizabethans, or perhaps we should say of Lamb and Keats. But in 1829 he struck a note more intimately his own in the Dream of Eugene Aram, a poem of strange fascination, and exhibiting an extraordinary faculty for ‘moving a horror skilfully’ and laying bare the tortured human heart.

Many of his sonnets are beautiful, and not a few of his detached songs and ballads (e.g., Fair Inez, I remember, It was the time of Roses) have that rare merit of tunefulness which is as much in the matter as in the metre. Here and there, too, as in the Death-Bed, he touches the keenest chord of pathos. But what is most noteworthy is that this purely poetical faculty does not seem to have declined in the popularity of his lesser labours, but rather to have increased in spite of it. His best pieces in this way were written in the last years of his life, when he may almost be said to have entered the Valley of the Shadow.

In Punch for Christmas, 1843, appeared the "Song of the Shirt," a poem with which his name is usually associated. It was the sharp and exceeding bitter cry of the hitherto inarticulate,— the sudden wail, not of the poor seamstress alone, but of the whole body of the under-paid and over-worked, fighting out their grim duel with Hunger. It rang through the length and breadth of the land, arousing and quickening a compassion which to this day has not wholly faded out. Such a production it is waste of time to criticise: it reaches its mark so surely and swiftly that mere questions of detail and technique seem to be impertinent superfluities.

But the "Bridge of Sighs," which appeared a few months after in Hood’s Magazine, is, in our opinion, superior as a work of art. "The Lady’s Dream" and the "Lay of the Labourer", which belong to the same periodical, have less merit. "The Haunted House", with which its pages opened in January, 1844, is a masterpiece of a different order. It is an extraordinarily minute study of disuse and decay,— of the ghostliness and horror that broods and gathers about neglect:—

‘With shatter’d panes the grassy court was starr’d;

The time-worn coping-stone had tumbled after,

And through the ragged roof the sky shone, barr’d

With naked beam and rafter.

‘O’er all there hung a shadow and a fear;

A sense of mystery the spirit daunted,

And said, as plain as whisper in the ear,

The place is Haunted!’

The latter verse recurs throughout the poem with singular effect. The length of the piece places it beyond the limits of quotation; but the selection given will show sufficiently how simple and sincere,—how strong in the abiding elements of song were the more serious efforts of this gentlest and most patient of poets.[5]

Recognition[]

Application was made by a number of Hood's friends to Sir Robert Peel to place Hood's name on the pension list with which the British state rewarded literary men. Peel was known to be an admirer of Hood's work and in the last few months of Hood's life he gave Jane Hood a pension of £100 without her husband's knowledge, to alleviate the family's debts.[6]

The pension that Peel's government had bestowed upon Hood was continued to his wife and family after his death. Jane Hood, who also suffered from poor health and had expended tremendous energy tending to her husband in his last year, died only 18 months after Hood. The pension then ceased but Lord John Russell, grandfather of philosopher Bertrand Russell, made arrangements for a £50 pension for the maintenance of Hood's 2 children, Francis and Tom.[7]

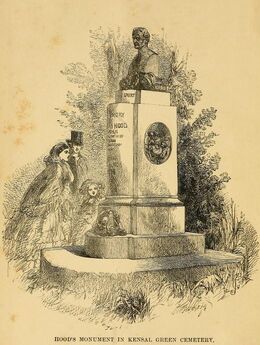

Hood's monument in Kensal Green cemetery, from The Collected Poems of Thomas Hood, 1880. Courtesy Internet Archive.

in 1854 a public monument, adorned with bas-reliefs from "Eugene Aram's Dream" and the "Bridge of Sighs," and inscribed, "He sang the Song of the Shirt,"[3] raised by public subscription, was erected to him in Kensal Green Cemetery, inaugurated by Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton.[8] Writer and friend of Hood, William Makepeace Thackeray, gave this assessment of Hood: "Oh sad, marvelous picture of courage, of honesty, of patient endurance, of duty struggling against pain!... Here is one at least without guile, without pretension, without scheming, of a pure life, to his family and little modest circle of friends tenderly devoted."[8]

His complete works have been edited thrice; the last time (1882–4) in 11 volumes. His poems were edited by Canon Ainger in 1897.[3]

8 of Hood's poems ("Autumn," "Silence," "Death," "Fair Ines," "Time of Roses," "Ruth," "The Death-bed," and "The Bridge of Sighs") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[9]

In popular culture[]

- The Piano - Jane Campion (1993)

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Odes and Addresses to Great People. London: Baldwin, Craddock, & Joy, 1825.

- Whims and Oddities: In prose and verse, with forty original designs. London: L. Relfe, 1826; London: Charles Tilt, 1827. (two series, 1826 and 1827)

- The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies, Hero and Leander, Lycus the Centaur, and other poems. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1827; Philadelphia: E. Littell, 1827.

- The Dream of Eugene Aram, the Murderer. London: Charles Tilt, 1831; New York: Peabody, 1832.

- Up the Rhine. London: A.H. Baily, 1840; Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1840.

- Poems of Wit and Humour. London: Edward Moxon, 1846.

- Poems. (2 volumes), London: Edward Moxon, 1846; New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1846. Volume I, Volume II.

- Whimsicalities. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 19845; New York: Putnam, 1852.

- Humorous Poems (edited by Epes Sargent). Boston: 1856.

- Poetical Works (with introduction by William Michael Rossetti). Little, Brown, 1857.[10]

- Whims and Waifs. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1860.

- Complete Poetical Works. (3 volumes), New York: H.W. Derby, 1861; New York: Putnam, 1869. [Volume I], [Volume Ii], Volume III.

- Serious Poems. London: Edward Moxon, 1868.

- (edited by Walter Jerrold). London & New York: H. Frowde, 1906.

- The Comic Poems. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

- new edition (edited by Tom Hood). London: Edward Moxon, 1876.

- The Poetical Works: Second series. London: Ward, Lock, 1879; London: Edward Moxon, 1880.

- Poetical Works. London & New York: Routledge, 1880.

- Humorous Poems (illustrated by Charles E. Brock; with preface by Alfred Ainger). London & New York: Macmillan, 1893.

- The Haunted House. London: Laurence & Bullen, 1896.

- Poems (edited by Alfred Ainger). London: Macmillan, 1897. Volume I: Serious poems, Volume II: Humorous poems

- Selected Poems. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Poems (edited by Clifford Byment). London: Grey Walls Press, 1948.

Novels[]

- Tylney Hall (novel). (3 volumes), London: A.H. Baily, 1834; Philadelphia: Cary, Lea & Blanchard, 1834. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

Short fiction[]

- National Tales (short novelettes). (2 volumes), London: William H. Ainsworth, 1827.

- The National and Humorous Prose Tales of Thomas Hood. London : Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent / Glasgow: Thomas D. Morison, [18--]

- The Prose Works of Thomas Hood. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1843.

- Tales, Romances, and Extravaganzas. New York: Putnam, Hurd, & Houghton, 1866.

Non-fiction[]

- Thomas Hood and Charles Lamb: The story of a friendship; being the literary reminiscences of Thomas Hood (edited by Walter Jerrold). London: Ernest Benn, 1930.

Edited[]

- The Comic Annual. London: Hurst, Chance, 1830–1842.

- Hood's Magazine. London: H. Hurst, 1845-1849.

Collected editions[]

- Hood's Own; or, Laughter from year to year. Lindon: A.H. Bailey, 1839.

- Second series. London: Edward Moxon, 1861.

- Prose and Verse. New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845.

- Hood's Own: Selected papers. New York: Putnam, 1852.

- The Works: Comic and serious(edited by his son). London: Edward Moxon, 1862; New York: Derby & Jackson, 1861. Volume I, Volume II.

- The Choice Works of Thomas Hood. New York: Kiggins & Kellogg, 1854

- The Choice Works of Thomas Hood: In prose and verse(edited by Richard Herne Shepherd). London: Chatto & Windus, 1876.

Letters[]

- The Letters of Thomas Hood (edited by Peter F. Morgan).. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[11]

Thomas Hood - I Remember, I Remember

Poems by Thomas Hood[]

The Poetry of Thomas Hood - A Sample

See also[]

References[]

- John Clubbe, Victorian Forerunner; The later career of Thomas Hood. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1968.

Garnett, Richard (1891) "Hood, Thomas (1799-1845)" in Lee, Sidney Dictionary of National Biography 27 London: Smith, Elder, pp. 270-272. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 11, 2017.

- J.C. Reid, Thomas Hood. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Hood, Thomas," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 196-197. Web, Jan. 29, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Garnett, 270.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Garnett, 271.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Garnett, 272.

- ↑ from Henry Austin Dobson, "Critical Introduction: Thomas Hood (1799–1845)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 16, 2016.

- ↑ Clubbe, p.181.

- ↑ Clubbe, p.196.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Reid, p.235

- ↑ Alphabetical list of authors: Daniel, Samuel to Hyde, Douglas, Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919). Bartleby.com, Web, May 18, 2012.

- ↑ The Poetical works of Thomas Hood (Volume 1), Google Books, Google, Web, Apr. 2, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Thomas Hood, WorldCat, OCLC , Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Sep. 2, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- 3 poems by Hood: "Sonnet for the 14th of February," "Ode: Autumn," "No!"

- Hood in The English Poets: An anthology: "The Bridge of Sighs," "A Parental Ode to My Son, Aged Three Years and Five Months," "The Death-Bed"

- Thomas Hood 1799-1845 at the Poetry Foundation

- Hood in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900: "Autumn," "Silence," "Death," "Fair Ines," "Time of Roses," "Ruth," "The Death-bed," "The Bridge of Sighs"

- Hood, Thomas (1799-1845) (5 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- Thomas Hood (1799-1845 info & 7 poems at English Poetry, 1579-1830

- Hood in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "The Dream of Eugene Aram," "Flowers," "Fair Ines," "The Death-Bed," "Ballad," "Lear," "Ballad," "Ruth," "The Water Lady," "Ode: Autumn," "The Song of the Shirt," "The Lay of the Labourer," "The Bridge of Sighs," "Stanzas"

- From “Miss Kilmansegg and Her Precious Leg:" I. "Her Death", II. "Her Moral"

- Thomas Hood at Poets' Corner

- Thomas Hood at PoemHunter (102 poems)

- Thomas Hood at the Poetry Archive.

- Books

- Works by Thomas Hood at Project Gutenberg

- Thomas Hood at Amazon.com

- Works by or about Thomas Hood in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Audio / video

- Thomas Hood poems at YouTube

- About

- Thomas Hood in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Hood, Thomas in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Thomas Hood at NNDB

- Thomas Hood (1799-1845): A Brief Biography at the Victorian Web

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100205145839/http://gerald-massey.org.uk/hood/index.htm Thomas Hood] at gerald-massey.org.uk

- George Saintsbury, "Thomas Hood", Macmillan's Magazine, Vol. LXII, May to Oct., 1890, pp. 422-430.

- Walter Jerrold, Thomas Hood; His Life and Times. New York: John Lane, 1909.

- Hood in Scotland (edited by Alex Elliott). Dundee: James P. Matthew & Co., 1885.

- Francis Hood, The Memorials of Thomas Hood. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860. Volume I, Volume II

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the Dictionary of National Biography (edited by Leslie Stephen). London: Smith, Elder, 1885-1900. Original article is at: Hood, Thomas (1799-1845)

|