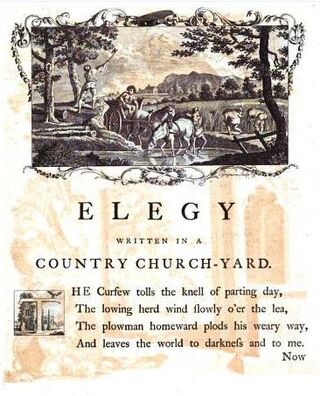

First page of Dodsley's illustrated edition of Gray's Elegy with illustration by Richard Bentley

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard is a poem by Thomas Gray, completed in 1750 and first published in 1751. The poem’s origins are unknown, but it was partly inspired by Gray’s thoughts following the death of the poet Richard West in 1742. Originally titled Stanza's Wrote in a Country Church-Yard, the poem was completed when Gray was living near the Stoke Poges churchyard. It was sent to his friend Horace Walpole, who popularised the poem among London literary circles.

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard[]

St. Michael's Church of Ireland, Castlecaulfield, Co. Tyrone, Ireland, 2011. Photo by Kenneth Allen. Licensed under Creative Commons, courtesy Geograph.org.

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea,

The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimm'ring landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow'r

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wand'ring near her secret bow'r,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,

The swallow twitt'ring from the straw-built shed,

The cock's shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

No children run to lisp their sire's return,

Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the poor.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Nor you, ye proud, impute to these the fault,

If Mem'ry o'er their tomb no trophies raise,

Where thro' the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault

The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flatt'ry soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway'd,

Or wak'd to ecstasy the living lyre.

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

Rich with the spoils of time did ne'er unroll;

Chill Penury repress'd their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flow'r is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood.

Th' applause of list'ning senates to command,

The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

To scatter plenty o'er a smiling land,

And read their hist'ry in a nation's eyes,

Their lot forbade: nor circumscrib'd alone

Their growing virtues, but their crimes confin'd;

Forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne,

And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

Or heap the shrine of Luxury and Pride

With incense kindled at the Muse's flame.

Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife,

Their sober wishes never learn'd to stray;

Along the cool sequester'd vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenor of their way.

Yet ev'n these bones from insult to protect,

Some frail memorial still erected nigh,

With uncouth rhymes and shapeless sculpture deck'd,

Implores the passing tribute of a sigh.

Their name, their years, spelt by th' unletter'd muse,

The place of fame and elegy supply:

And many a holy text around she strews,

That teach the rustic moralist to die.

For who to dumb Forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e'er resign'd,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing, ling'ring look behind?

On some fond breast the parting soul relies,

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

Ev'n from the tomb the voice of Nature cries,

Ev'n in our ashes live their wonted fires.

For thee, who mindful of th' unhonour'd Dead

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,

Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

"Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

Brushing with hasty steps the dews away

To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.

"There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

"Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

Mutt'ring his wayward fancies he would rove,

Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

Or craz'd with care, or cross'd in hopeless love.

"One morn I miss'd him on the custom'd hill,

Along the heath and near his fav'rite tree;

Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

"The next with dirges due in sad array

Slow thro' the church-way path we saw him borne.

Approach and read (for thou canst read) the lay,

Grav'd on the stone beneath yon aged thorn."

"Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" by Thomas Gray (read by Tom O'Bedlam)

THE EPITAPH

Here rests his head upon the lap of Earth

A youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown.

Fair Science frown'd not on his humble birth,

And Melancholy mark'd him for her own.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heav'n did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to Mis'ry all he had, a tear,

He gain'd from Heav'n ('twas all he wish'd) a friend.

No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

(There they alike in trembling hope repose)

The bosom of his Father and his God.

Synopsis[]

The poem is an elegy in name but not in form; it employs a similar style to contemporary odes, but it embodies a meditation on death, and remembrance after death. The poem argues that the remembrance can be good and bad, and the narrator finds comfort in pondering the lives of the obscure rustics buried in the churchyard. The two versions of the poem, Stanzas and Elegy, approach death differently; the first contains a stoic response to death, but the final version contains an epitaph which serves to repress the narrator's fear of dying. With its discussion of, and focus on, the obscure and the known, the poem has possible political ramifications, but it does not make any definite claims on politics to be more universal in its approach to life and death.

History[]

Thomas Gray

Gray's life was surrounded by loss and death, and many people that he knew died painfully and alone. In 1749, several events occurred that caused Gray stress. On 7 November, Mary Antrobus, Gray's aunt, died; her death devastated his family. The loss was compounded a few days later by news that his friend since childhood[1] Horace Walpole was almost killed by two highwaymen.[2] Although Walpole survived and later joked about the event, the incident disrupted Gray's ability to pursue his scholarship.[3] The events dampened the mood that Christmas, and Antrobus's death was ever fresh in the minds of the Gray family. As a side effect, the events caused Gray to spend much of his time contemplating his own mortality. As he began to contemplate various aspects of mortality, he combined his desire to determine a view of order and progress present in the Classical world with aspects of his own life. With spring nearing, Gray questioned if his own life would enter into a sort of rebirth cycle or, should he die, if there would be anyone to remember him. Gray's meditations during spring 1750 turned to how individuals' reputations would survive. Eventually, Gray remembered some lines of poetry that he composed in 1742 following the death of West, a poet he knew. Using that previous material, he began to compose a poem that would serve as an answer to the various questions he was pondering.[4]

On 3 June 1750, Gray moved to Stoke Poges, and on 12 June he completed Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. Immediately, he included the poem in a letter he sent to Walpole, that said:[5]

- As I live in a place where even the ordinary tattle of the town arrives not till it is stale, and which produces no events of its own, you will not desire any excuse from me for writing so seldom, especially as of all people living I know you are the least a friend to letters spun out of one's own brains, with all the toil and constraint that accompanies sentimental productions. I have been here at Stoke a few days (where I shall continue good part of the summer); and having put an end to a thing, whose beginnings you have seen long ago. I immediately send it you. You will, I hope, look upon it in light of a thing with an end to it; a merit that most of my writing have wanted, and are like to want, but which this epistle I am determined shall not want.[5]

The letter reveals that Gray felt that the poem was unimportant, and that he did not expect it to become as popular or influential as it did. Gray dismisses its positives as merely being that he was able to complete the poem, which was probably influenced by his experience of the churchyard at Stoke Poges, where he attended the Sunday service and was able to visit the grave of Antrobus.[6]

The version that was later published and reprinted was a 32-stanza version with the "Epitaph" conclusion. Before the final version was published, it was circulated in London society by Walpole, who ensured that it would be a popular topic of discussion throughout 1750. By February 1751, Gray received word that William Owen, the publisher of the Magazine of Magazines, would print the poem on 16 February; the copyright laws of the time did not require Gray's approval for publication. With Walpole's help, he was able to convince Robert Dodsley to print the poem on 15 February as a quarto pamphlet.[7]

Walpole added a preface to the poem reading: "The following POEM came into my hands by Accident, if the general Approbation with which this little Piece has been spread, may be call'd by so slight a Term as Accident. It is the Approbation which makes it unnecessary for me to make any Apology but to the Author: As he cannot but feel some Satisfaction in having pleas'd so many Readers already, I flatter myself he will forgive my communicating that Pleasure to many more."[8]

The pamphlet contained woodblock illustrations and was printed without attribution to Gray, at his request. Immediately after, Owen's magazine with Gray's poem was printed but contained multiple errors and other problems. In a 20 February letter to Walpole, Gray thanked him for intervening and helping to get a quality version of the poem published before Owen.[9]

The poem quickly became popular. It was printed many times, translated into many languages, and praised by critics even after Gray's other poetry had fallen out of favour. Later critics tended to praise its language and universal aspects, but some felt the ending was unconvincing, failing to resolve the questions the poem raised; or that the poem did not do enough to present a political statement that would serve to help the obscure rustic poor who forms its central image.

It was so popular that it was reprinted twelve times and reproduced in many different periodicals until 1765,[10] including in Gray's Six Poems (1753), in his Odes (1757),[11] and in Volume IV of Dodsley's 1755 compilation of poetry.[12] The revised version of 1768 was that later printed.[13] There were many translations of the poem, including Latin versions by Christopher Anstey and Robert Lloyd in 1762. Other translations include into Italian by Melchiorre Cesarotti (1772), Giuseppe Torelli (1776), and Giacomo Zanella (1869), into Russian by Vasily Zhukovsky (1802 and 1839), into Welsh by Thomas Jones of Denbigh (1831), and into Greek by George Denman (1871). The poem was translated into Spanish by 1823 and Japanese by 1882.[14]

Composition[]

Holograph manuscript of Gray's "Stanzas Wrote in a Country Church-yard"

The poem most likely originated in the poetry that Gray composed in 1742. William Mason, in Memoirs, discussed his friend Gray and the origins of Elegy: "I am inclined to believe that the Elegy in a Country Church-yard was begun, if not concluded, at this time [August 1742] also: Though I am aware that as it stands at present, the conclusion is of a later date; how that was originally I shall show in my notes on the poem."[15] Mason's argument was a guess, but he argued that one of Gray's poems from the Eton Manuscript, a copy of Gray's handwritten poems owned by Eton College, was a 22-stanza rough draft of the Elegy called "Stanza's Wrote in a Country Church-Yard". The manuscript copy contained many ideas which were reworked and revised as he attempted to work out the ideas that would later form the Elegy. A later copy was entered into Gray's commonplace book and a third version, included in an 18 December 1750 letter, was sent to Thomas Wharton. The draft sent to Walpole was subsequently lost.[16]

There are two possible ways the poem was composed. The first, Mason's concept, argues that the Eton copy was the original for the Elegy poem and was complete in itself. Later critics claimed that the original was more complete than the later version;[17] Roger Lonsdale argued that the early version had a balance that set up the debate, and was clearer than the later version. Lonsdale also argued that the early poem fits classical models, including Virgil's Georgics and Horace's Epodes.[18] The early version of the poem was finished, according to Mason, in August 1742, but there is little evidence to give such a definite date. Mason argued that the poem was in response to West's death, but there is little to indicate that Mason would have such information.[19]

Instead, Walpole wrote to Mason to say: "The Churchyard was, I am persuaded, posterior to West's death at least three or four years, as you will see by my note. At least I am sure that I had the twelve or more first lines from himself above three years after that period, and it was long before he finished it."[20]

The two did not resolve their disagreement, but Walpole did concede the matter, possibly to keep letters polite between the them. But Gray's outline of the events provides the second possible way the poem was composed: the first lines of the poem were written some time in 1746 and he probably wrote more of the poem during the time than Walpole claimed. The letters show the likelihood of Walpole's date for the composition, as a 12 June 1750 letter from Gray to Walpole stated that Walpole was provided lines from the poem years before and the two were not on speaking terms until after 1745. The only other letter to discuss the poem was one sent to Wharton on 11 September 1746, which alludes to the poem being worked on.[21]

Genre[]

The poem is not a conventional part of Theocritus's elegiac tradition, because it does not mourn an individual. The use of "elegy" is related to the poem relying on the concept of lacrimae rerum, or despair regarding the human condition. The poem lacks many standard features of the elegy: an invocation, mourners, flowers, and shepherds. The theme does not emphasise loss as do other elegies, and its natural setting is not a primary component of its theme. It can be included in the tradition as a memorial poem, although not necessarily for one person,[22] and the poem contains thematic elements of the elegiac genre, especially mourning.[23] The model for Gray's choice of genre and style is likely Milton's Lycidas but it lacks many of the ornamental aspects found in Milton's poem. Gray's poem is natural, whereas Milton's is more artificially designed.[24]

In evoking the English countryside, the poem is connected to the picturesque tradition found in John Dyer's Grongar Hill (1726), and later in James Beattie's The Minstrel (1771) and Richard Crowe's Lewesdon Hill (1788). "However, it diverges from this tradition in focusing on the death of a poet.[25] Much of the poem deals with questions that were linked to Gray's own life; during the poem's composition, he was confronted with the death of others and questioned his own mortality. Although universal in its statements on life and death, the poem was grounded in Gray's feelings about his own life, and served as an epitaph for himself. As such, it falls within an old poetic tradition of poets contemplating their legacy. The poem, as an elegy, also serves to lament the death of others, including West.[26] This is not to say that Gray's poem was like others of the graveyard school of poetry; instead, Gray tries to avoid a description that would evoke the horror common to other poems in the elegiac tradition. This is compounded further by the narrator trying to avoid an emotional response to death, by relying on rhetorical questions and discussing what his surroundings lack.[27]

The poem is connected to the ode tradition found within Gray's other works and in those of Joseph Warton and William Collins and to a lesser extent in English ballads.[28] The poem, as it developed from its original form, incorporated various traditional poetic techniques[29] and partly relied on the poetic metre of those like Petrarch.[30] Between the first and final versions, the poem becomes more like Milton and less like Horace in its form.[31] The poem actively relied on "English" techniques and language. The stanza form, quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, was common to English poetry and used throughout the 16th century. Any foreign diction that Gray relied on was merged with English words and phrases to give them an "English" feel. Many of the foreign words Gray adapted were previously used by William Shakespeare or John Milton, securing an "English" tone, and he emphasised monosyllabic words throughout his elegy to add a rustic English tone.[32]

Poem[]

The poem begins in a churchyard with a narrator who is describing his surroundings in vivid detail. The narrator emphasises both aural and visual sensations as he examines the area in relation to himself:[33]

- The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

- The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea

- The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

- And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

- Now fades the glimm'ring landscape on the sight,

- And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

- Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

- And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

- Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow'r

- The moping owl does to the moon complain

- Of such, as wand'ring near her secret bow'r,

- Molest her ancient solitary reign. (lines 1–12)

As the poem continues, the narrator begins to focus less on the countryside and more on his immediate surroundings. His descriptions begin to move from sensations to his own thoughts about the dead. As the poem changes, the narrator begins to emphasise what is not present in the scene, he contrasts an obscure country life with a life that is remembered. This contemplation provokes the narrator's thoughts on waste that comes in nature:[34]

- Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

- The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear:

- Full many a flow'r is born to blush unseen,

- And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

- Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

- The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

- Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

- Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood.

- The applause of listening senates to command,

- The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

- To scatter plenty o'er a smiling land,

- And read their hist'ry in a nation's eyes,

- Their lot forbade: nor circumscrib'd alone

- Their growing virtues, but their crimes confin'd;

- Forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne,

- And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

- The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

- To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

- Or heap the shrine of Luxury and Pride

- With incense kindled at the Muse's flame. (lines 53–72)

The narrator focuses on the inequities that come from death, obscuring individuals, while he begins to resign himself to his own inevitable fate. As the poem ends, the narrator begins to deal with death in a direct manner as he discusses how humans desire to be remembered. As the narrator does so, the poem shifts and the first narrator is replaced by a second who describes the death of the first:[35]

- For thee, who mindful of th' unhonour'd Dead

- Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

- If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

- Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,

- Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

- Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

- Brushing with hasty steps the dews away

- To meet the sun upon the upland lawn. (lines 93–100)

The poem concludes with a description of the poet's grave that the narrator is meditating over, together with a description of the end of that poet's life:[36]

- There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

- That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

- His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

- And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

- Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

- Mutt'ring his wayward fancies he would rove,

- Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

- Or craz'd with care, or cross'd in hopeless love.

- One morn I miss'd him on the custom'd hill,

- Along the heath and near his fav'rite tree;

- Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

- Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

- The next with dirges due in sad array

- Slow thro' the church-way path we saw him borne.

- Approach and read (for thou canst read) the lay,

- Grav'd on the stone beneath yon aged thorn." (lines 101–116)

An epitaph is included after the conclusion of the poem. The epitaph reveals that the poet whose grave is the focus of the poem was unknown and obscure. The poet was separated from the other common people because he was unable to join with the common affairs of life, and circumstance kept him from becoming something greater:[37]

- Here rests his head upon the lap of Earth

- A youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown.

- Fair Science frown'd not on his humble birth,

- And Melancholy mark'd him for her own.

- Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

- Heav'n did a recompense as largely send:

- He gave to Mis'ry all he had, a tear,

- He gain'd from Heav'n ('twas all he wish'd) a friend.

- No farther seek his merits to disclose,

- Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

- (There they alike in trembling hope repose)

- The bosom of his Father and his God. (lines 117–128)

The original conclusion from the earlier version of the poem promotes the view that humans should be resigned to the fact that we will die, which differs from the indirect, third person description in the final version:[38]

- The thoughtless World to majesty may bow

- Exalt the brave, & idolize Success

- But more to Innocence their Safety owe

- Than Power & Genius e'er conspired to bless

- And thou, who mindful of the unhonour'd Dead

- Dost in these Notes thy artless Tale relate

- By Night & lonely contemplation led

- To linger in the gloomy Walks of Fate

- Hark how the sacred Calm, that broods around

- Bids ev'ry fierce tumultous Passion ease

- In still small Accents whisp'ring from the Ground

- A grateful Earnest of eternal Peace

- No more with Reason & thyself at strife;

- Give anxious Cares & endless Wishes room

- But thro' the cool sequester'd Vale of Life

- Pursue the silent Tenour of thy Doom.

Themes[]

Frontispiece to 1753 edition of Elegy by Bentley

The poem is connected to many British poems that contemplate death and sought to make it more familiar and tame.[39] The elegy contemplates the death of the poet and is similar to other works within the British tradition, including Jonathan Swift's Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift, a satirical version of a eulogy.[40] When compared to other works by Graveyard poets, such as Blair's The Grave (1743), the poem has less emphasis on common images. His description of the moon, birds, and trees lacks the horror found in the other poems and Gray avoids mentioning the word "grave", instead using other words as euphemisms.[41]

There is a difference in tone between the two versions of the elegy; the early one ends with an emphasis on the narrator joining with the obscure common man, while the later version ends with an emphasis on how it is natural for humans to want to be known. The later ending also explores the narrator's own death, whereas the earlier version serves as a Christian consolation regarding death.

The first version of the elegy is among the few early poems composed by Gray in English, including "Sonnet on the Death of Richard West," his "Eton Ode", and his "Ode to Adversity". All four contain Gray's meditations on mortality that were inspired by West's death.[42] The later version of the poem kept the stoic resignation regarding death, as the narrator still accepts death. The poem concludes with an epitaph, which reinforces Gray's indirect and reticent manner of writing.[27] Although the ending reveals the narrator's repression of feelings surrounding his inevitable fate, it is optimistic. The epitaph describes faith in a "trembling hope" that he cannot know while alive.[43]

In describing the narrator's analysis of his surroundings, Gray employed John Locke's philosophy of the sensations, which argued that the senses were the origin of ideas. Information described in the beginning of the poem is reused by the narrator as he contemplates life near the end. The description of death and obscurity adopts Locke's political philosophy as it emphasises the inevitability and finality of death. The end of the poem is connected to Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding in that the beginning of the poem deals with the senses and the ending describes how we are limited in our ability to understand the world. The poem takes the ideas and transforms them into a discussion of blissful ignorance by adopting Locke's resolution to be content with our limited understanding. Unlike Locke, the narrator of the poem knows that he is unable to fathom the universe, but still questions the matter.[44]

On the difference between the obscure and the renowned in the poem, scholar David Cecil argued, "Death, he perceives, dwarfs human differences. There is not much to choose between the great and the humble, once they are in the grave. It may be that there never was; it may be that in the obscure graveyard lie those who but for circumstance would have been as famous as Milton and Hampden."[45] However, death is not completely democratic because "if circumstances prevented them from achieving great fame, circumstances also saved them from committing great crimes. Yet there is a special pathos in these obscure tombs; the crude inscriptions on the clumsy monuments are so poignant a reminder of the vain longing of all men, however humble, to be loved and to be remembered."[45]

The poem ends with the narrator turning towards his own fate, accepting his life and accomplishments. The poem, like many of Gray's, incorporates a narrator who is contemplating his position in a transient world that is mysterious and tragic.[46] Although the comparison between obscurity and renown is commonly seen as universal and not within a specific context with a specific political message, there are political ramifications for Gray's choices. Both John Milton and John Hampden spent time near the setting of Stoke Poges, which was also affected by the English Civil War. The poem's composition could also have been prompted by the entrance of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland into London or by a trial of Jacobite nobility in 1746.[47]

Many scholars, including Lonsdale, believe that the poem's message is too universal to require a specific event or place for inspiration, but Gray's letters suggest that there were historical influences in its composition.[48] In particular, it is possible that Gray was interested in debates over the treatment of the poor, and that he supported the political structure of his day, which was to support the poor who worked but look down on those that refused to. However, Gray's message is incomplete, because he ignored the poor's past rebellions and struggles.[49] The poem ignores politics to focus on various comparisons between a rural and urban life in a psychological manner. The argument between living a rural life or urban life lets Gray discuss questions that answer how he should live his own life, but the conclusion of the poem does not resolve the debate as the narrator is able to recreate himself in a manner that reconciles both types of life while arguing that poetry is capable of preserving those who have died.[50] It is probable that Gray wanted to promote the hard work of the poor but to do nothing to change their social position. Instead of making claims of economic injustice, Gray accommodates differing political views. This is furthered by the ambiguity in many of the poem's lines, including the statement "Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood" that could be read either as Oliver Cromwell being guiltless for violence during the English Civil War or merely as villagers being compared to the guilty Cromwell. The poem's primary message is to promote the idea of "Englishness", and the pastoral English countryside. The earlier version lacks many of the later version's English aspects, especially as Gray replaced many classical figures with English ones: Cato the Younger by Hampden, Tully by Milton, and Julius Caesar by Cromwell.[51]

Influence[]

In choosing an "English" feel to the language and setting, Gray provided a model for later poets wishing to describe England and the English countryside. His choice of language, words, and feelings that connected to rural England served as the model for Oliver Goldsmith's and William Cowper's works during the second half of the 18th century.[32] Beyond his own poetry, Goldsmith would play around with the lines of the poem by removing words to alter its meaning.[52] Gray's Elegy was highly influential and provoked a response from the Romantic poets. When William Wordsworth wrote the preface to Lyrical Ballads he responded to Gray's techniques and to the Elegy with his "Intimations of Immortality" ode. As a whole, the Romantics believed that Gray represented the poetic orthodoxy they were rebelling against in that he did not try to overcome death in his poem, but they used Gray's ideas when attempting to define their own beliefs.[53] Gray also influenced how Wordsworth described his education and the death of his father in The Prelude.[54] As a schoolboy, Percy Bysshe Shelley translated part of the Elegy into Latin and visited the churchyard at Stoke Poges.[55] Later, in 1815, when Shelley stayed in Lechlade, he again visited the churchyard, and composed "A Summer Evening Churchyard, Lechlade, Gloucestershire", which echoes the language of Gray.[56]

Gray's influence lasted throughout the Victorian and Modern periods. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, subsequently adopted many features of the Elegy in his poem In Memoriam. He established a ceremonial, almost religious, tone by reusing the idea of the "knell" and "toll" to mark the coming night. This is followed with the poet narrator looking through letters of his deceased friend, echoing Gray's narrator reading the tombstones to connect to the deceased.[57] Robert Browning relied on a similar setting to the Elegy in his pastoral poem "Love Among the Ruins", which describes the desire for glory and how everything ends in death. Unlike Gray, Burns adds a female figure and argues that nothing but love matters.[58] Thomas Hardy memorised Gray's Elegy, and the poem influenced his collection Wessex Poems and Other Verses (1898). Many of Hardy's poems contained a graveyard theme, and he based his poems on Gray's views. In particular, "Friends Beyond" was modelled on the Elegy. Even the frontispiece to the collection contained an image of a graveyard with a reference to the first line of the elegy.[59]

It is possible that parts of T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets are derived from Gray's elegy, although Eliot believed that Gray's diction, along with 18th-century poetic diction in general, was restrictive and limited. The Four Quartets covers many of the same views, and Eliot's village is similar to Gray's hamlet. There are many echoes of Gray's language throughout the Four Quartets; both poems rely on the yew tree as an image and use the word "twittering", which was uncommon at the time. Each of Eliot's four poems have parallels to Gray's poem, but "Little Gidding" is deeply indebted to the elegy's meditation on a "neglected spot". Of the similarities between the poems, it is Eliot's reuse of Gray's image of "stillness" that forms the strongest parallel, an image that is essential to the poem's arguments on mortality and society.[60]

Critical response[]

Memorial at Stoke Poges dedicated to the elegy

The immediate response to the final draft version of the poem was positive, and Walpole was very pleased with the work. During the summer of 1750, Gray received so much positive support regarding the poem that he was in dismay, but did not mention it in his letters until an 18 December 1750 letter to Wharton. In the letter, Gray said,[61]

The Stanza's, which I now enclose to you have had the Misfortune by Mr W:s Fault to be made ... publick, for which they certainly were never meant, but it is too late to complain. They have been so applauded, it is quite a Shame to repeat it. I mean not to be modest; but I mean, it is a shame for those who have said such superlative Things about them, that I can't repeat them. I should have been glad, that you & two or three more People had liked them, which would have satisfied my ambition on this head amply.[62]

The poem was praised for its universal aspects,[47] and Gray became one of the most famous English poets of his era. Despite his popularity, after his death only his elegy remained popular until 20th-century critics began to re-evaluate his poetry.[63] The 18th-century writer James Beattie was said by Sir William Forbes, 6th Baronet to have written a letter to him claiming, "Of all the English poets of this age, Mr. Gray is most admired, and I think with justice; yet there are comparatively speaking but a few who know of anything of his, but his 'Church-yard Elegy,' which is by no means the best of his works."[64]

The poem remained popular, and, in Canadian history, it is claimed that the British General James Wolfe read the poem before his British troops arrived at the Plains of Abraham in September 1759 as part of the Seven Years' War. After reading the poem, he is reported to have said: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written those lines than take Quebec tomorrow."[65] Adam Smith, in his 21st lecture on rhetoric in 1763, argued that poetry should deal with "A temper of mind that differs very little from the common tranquillity of mind is what we can best enter into, by the perusal of a small piece of a small length ... an Ode or Elegy in which there is no odds but in the measure which differ little from the common state of mind are what most please us. Such is that on the Church yard, or Eton College by Mr Grey. The Best of Horaces (tho inferior to Mr Greys) are all of this sort."[66] Even Samuel Johnson, who knew Gray but did not like his poetry, later praised the poem when he wrote in his Life of Gray (1779) that it "abounds with images which find a mirror in every breast; and with sentiments to which every bosom returns an echo. The four stanzas beginning Yet even these bones, are to me original: I have never seen the notions in any other place; yet he that reads them here, persuades himself that he has always felt them."[67] Many reviews of Johnson's Lives of the Poets thought that Johnson was too harsh towards Gray, but a 1781 review in the Critical Review declared, "On his Elegy in a Country Church-Yard, we agree with Dr. Johnson, that too much praise cannot well be lavished;"[68] Attacks continued until a 1782 review of the work in the Annual Register, which proclaimed, "That the doctor was not over zealous to allow him the degree of praise that the public voice had universally assigned him, is, we think, sufficiently apparent. Partiality to his beautiful elegy, had perhaps allotted him a rank above his general merits."[69]

Later response[]

Johnson's critical analysis of the poem prompted many others to write their own critiques debating the poem's merits. In 1783, John Young wrote an expansion to Johnson’s Life of Gray and claimed, "The Elegy written in a Country Church Yard has become a staple in English poetry. It is even beginning to get into years."[70] After analysing each aspect of the poem, Young concluded by describing how the anthropomorphised "Criticism" would respond to the poem: "In examining the Elegy written in a Country Church-yard, she has found much room for censure, and some room for praise. The Piece has been much over-rated; and many serious persons, who mediate on death from a sense of duty, consider Conscience as concerned in their finding this Meditation perfect. Of perfections no doubt it contains some; but it contains blemishes too; and if Criticism grant it nothing but its merit, what then will be its praise?"[71] Beyond John Young, other writers produced criticisms of "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" in response to Johnson's critique. Robert Potter's 1783 is a general defence of Gray, John Scott's Critical Essays (1785) praised the poem along with a close analysis of the text, and Wakefield's 1785 edition of Gray's poems refuted various statements made by Johnson in the notes to the text.[72] In 1785, Gilbert Wakefield produced a 207 page edition of the elegy with Gray's other poems with copious footnotes and notes to criticism provided in scholarship since the poem's publication.[73] Following in 1791 was James Boswell's Life of Johnson, which provided more statements by Johnson on Gray: "Sir, I do not think Mr. Gray a superior sort of poet. He has not a bold imagination, nor much command of words. The obscurity in which he has involved himself will not make us think him sublime. His Elegy in a Churchyard has a happy selection of images, but I don't like his great things."[74] Boswell adds that his own view of Gray was far more positive to respond to both critics of Johnson's view and to Johnson's writing.[75]

Debate over the poem's merits continued into the 19th century, and Victorian critics were unconvinced by the poem's merits. The Romantic poet William Wordsworth, in his "Preface" to Lyrical Ballads attacked Gray's use of poetic diction but also relied heavily on Gray's techniques and ideas.[76] The later Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was an admirer of the poem and influenced by it,[56] as was Thomas Hardy, who knew the poem by heart.[77] At the end of the century, Matthew Arnold, in his 1881 collection of critical writings, said, "The Elegy pleased; it could not but please: but Gray's poetry, on the whole, astonished his contemporaries at first more than it pleased them; it was so unfamiliar, so unlike the sort of poetry in vogue."[78] In 1882, Edmund Gosse analyzed the reception of Gray's poem: "It is curious to reflect upon the modest and careless mode in which that poem was first circulated which was destined to enjoy and to retain a higher reputation in literature than any other English poem perhaps than any other poem of the world written between Milton and Wordsworth."[79] He continued by stressing the widespread nature of the poem: "The fame of the Elegy has spread to all countries and has exercised an influence on all the poetry of Europe from Denmark to Italy from France to Russia With the exception of certain works of Byron and Shakespeare no English poem has been so widely admired and imitated abroad and after more than a century of existence we find it as fresh as ever when its copies even the most popular of all those of Lamar tine are faded and tarnished."[80] He concluded with a reinforcing claim on the poem's place in English poetry: "It possesses the charm of incomparable felicity of a melody that is not too subtle to charm every ear of a moral persuasiveness that appeals to every generation and of metrical skill that in each line proclaims the master The Elegy may almost be looked upon as the typical piece of English verse our poem of poems not that it is the most brilliant or original or profound lyric in our language but because it combines in more balanced perfection than any other all the qualities that go to the production of a fine poetical effect."[80] An anonymous review of Gray in the 12 December 1896 The Academy claimed that "Gray's 'Elegy' and Goldsmith's 'Deserted Village' shine forth as the two human poems in a century of artifice."[81]

20th-century response[]

Critics at the beginning of the 20th century believed that the poem's use of sound and tone made it great. The French critic Louis Cazamian claimed in 1927 that Gray "discovered rhythms, utilised the power of sounds, and even created evocations. The triumph of this sensibility allied to so much art is to be seen in the famous Elegy, which from a somewhat reasoning and moralizing emotion has educed a grave, full, melodiously monotonous song, in which a century weaned from the music of the soul tasted all the sadness of eventide, of death, and of the tender musing upon self."[82] I. A. Richards, following in 1929, declared that the merits of the poem come from its tone: "poetry, which has no other very remarkable qualities, may sometimes take very high rank simply because the poet's attitude to his listeners – in view of what he has to say – is so perfect. Gray and Dryden are notable examples. Gray's Elegy, indeed, might stand as a supreme instance to show how powerful an exquisitely adjusted tone may be. It would be difficult to maintain that the thought in this poem is either striking or original, or that its feeling is exceptional."[83] He continued: "the Elegy may usefully remind us that boldness and originality are not necessities for great poetry. But these thoughts and feelings, in part because of their significance and their nearness to us, are peculiarly difficult to express without faults ... Gray, however, without overstressing any point composes a long address, perfectly accommodating his familiar feelings towards the subject and his awareness of the inevitable triteness of the only possible reflections, to the discriminating attention of his audience. And this is the source of his triumph."[84]

In the 1930s and 1940s, critics emphasised the content of the poem, and some felt that it fell short of what was necessary to make it truly great. In 1930, William Empson, while praising the form of the poem as universal, argued against its merits because of its potential political message. He claimed that the poem "as the context makes clear", means that "18th-century England had no scholarship system of carriere ouverte aux talents. This is stated as pathetic, but the reader is put into a mood in which one would not try to alter it ... By comparing the social arrangement to Nature he makes it seem inevitable, which it was not, and gives it a dignity which was undeserved. Furthermore, a gem does not mind being in a cave and a flower prefers not to be picked; we feel that man is like the flower, as short-lived, natural, and valuable, and this tricks us into feeling that he is better off without opportunities."[85] He continued: "the truism of the reflection in the churchyard, the universality and impersonality this gives to the style, claim as if by comparison that we ought to accept the injustice of society as we do the inevitability of death."[86] T. S. Eliot’s 1932 collection of essays contained a comparison of the elegy to the sentiment found in metaphysical poetry: "The feeling, the sensibility, expressed in the Country Churchyard (to say nothing of Tennyson and Browning) is cruder than that in the Coy Mistress."[87] Later, in 1947, Cleanth Brooks pointed out that "In Gray's poem, the imagery does seem to be intrinsically poetic; the theme, true; the 'statement', free from ambiguity, and free from irony."[88] After describing various aspects and complexities within the poem, Brooks provided his view on the poem's conclusion: "the reader may not be altogether convinced, as I am not altogether convinced, that the epitaph with which the poem closes is adequate. But surely its intended function is clear, and it is a necessary function if the poem is to have a structure and is not to be considered merely a loose collection of poetic passages."[89]

Critics during the 1950s and 1960s generally regarded the Elegy as powerful, and emphasised its place as one of the great English poems. In 1955, R. W. Ketton-Cremer argued, "At the close of his greatest poem Gray was led to describe, simply and movingly, what sort of man he believed himself to be, how he had fared in his passage through the world, and what he hoped for from eternity."[90] Regarding the status of the poem, Graham Hough in 1953 explained, "no one has ever doubted, but many have been hard put to it to explain in what its greatness consists. It is easy to point out that its thought is commonplace, that its diction and imagery are correct, noble but unoriginal, and to wonder where the immediately recognizable greatness has slipped in."[91] Following in 1963, Martin Day argued that the poem was "perhaps the most frequently quoted short poem in English."[13] Frank Brady, in 1965, declared, "Few English poems have been so universally admired as Gray's Elegy, and few interpreted in such widely divergent ways."[92] Patricia Spacks, in 1967, focused on the psychological questions in the poem and claimed that "For these implicit questions the final epitaph provides no adequate answer; perhaps this is one reason why it seems not entirely a satisfactory conclusion to the poem."[93] She continued by praising the poem: "Gray's power as a poet derives largely from his ability to convey the inevitability and inexorability of conflict, conflict by its nature unresolvable."[94] In 1968, Herbert Starr pointed out that the poem was "frequently referred to, with some truth, as the best known poem in the English language."[95]

During the 1970s, some critics pointed out how the lines of the poems were memorable and popular while others emphasised the poem's place in the greater tradition of English poetry. W. K. Wimsatt, in 1970, suggested, "Perhaps we shall be tempted to say only that Gray transcends and outdoes Hammond and Shenstone simply because he writes a more poetic line, richer, fuller, more resonant and memorable in all the ways in which we are accustomed to analyze the poetic quality."[96] In 1971, Charles Cudworth declared that the elegy was "a work which probably contains more famous quotations per linear inch of text than any other in the English language, not even excepting Hamlet."[97] When describing how Gray's Elegy is not a conventional elegy, Eric Smith added in 1977, "Yet, if the poem at so many points fails to follow the conventions, why are we considering it here? the answer is partly that no study of major English elegies could well omit it. But it is also, and more importantly, that in its essentials Gray's Elegy touches this tradition at many points, and consideration of them is of interest to both to appreciation of the poem and to seeing how [...] they become in the later tradition essential points of reference."[98] Also in 1977, Thomas Carper noted, "While Gray was a schoolboy at Eton, his poetry began to show a concern with parental relationships, and with his position among the great and lowly in the world [...] But in the Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard these longstanding and very human concerns have their most affecting expression."[99] In 1978, Howard Weinbrot noted, "With all its long tradition of professional examination the poem remains distant for many readers, as if the criticism could not explain why Johnson thought that "The Church-yard abounds with images that find a mirrour in every mind[...]".[100] He continued by arguing that it is the poem's discussion of morality and death that is the source of its "enduring popularity".[101]

By the 1980s, critics emphasised the power of the poem's message and technique, and it was seen as an important English poem. After analyzing the language of the poem, W. Hutchings declared in 1984, "The epitaph, then, is still making us think, still disturbing us, even as it uses the language of conventional Christianity and conventional epitaphs. Gray does not want to round his poem off neatly, because death is an experience of which we cannot be certain, but also because the logic of his syntax demands continuity rather than completion."[102] Also in 1984, Anne Williams claimed, "ever since publication it has been both popular and universally admired. Few readers then or now would dispute Dr. Johnson's appraisal [...] In the twentieth century we have remained eager to praise, yet praise has proved difficult; although tradition and general human experience affirm that the poem is a masterpiece, and although one could hardly wish a single word changed, it seems surprisingly resistant to analysis. It is lucid, and at first appears as seamless and smooth as monumental alabaster."[103] Harold Bloom, in 1987, claimed, "What moves me most about the superb Elegy is the quality that, following Milton, it shares with so many of the major elegies down to Walt Whitman's [...] Call this quality the pathos of a poetic death-in-life, the fear that one either has lost one's gift before life has ebbed, or that one may lose life before the poetic gift has expressed itself fully. This strong pathos of Gray's Elegy achieves a central position as the antithetical tradition that truly mourns primarily a loss of the self."[104] In 1988, Morris Golden, after describing Gray as a "poet's poet" and places him "within the pantheon of those poets with whom familiarity is inescapable for anyone educated in the English language" declared that in "the 'Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard,' mankind has felt itself to be directly addressed by a very sympathetic, human voice."[105] He later pointed out: "Gray's 'Elegy' was universally admired in his lifetime and has remained continuously the most popular of mid-eighteenth-century English poems; it is, as Gosse has called it, the standard English poem. The reason for this extraordinary unanimity of praise are as varied as the ways in which poetry can appeal. The 'Elegy' is a beautiful technical accomplishment, as can be seen even in such details as the variation of the vowel sounds or the poet's rare discretion in the choice of adjectives and adverbs. Its phrasing is both elegant and memorable, as is evident from the incorporation of much of it into the living language."[106]

Modern critics emphasised the poem's use of language as a reason for its importance and popularity. In 1995, Lorna Clymer argued, "The dizzying series of displacements and substitutions of subjects, always considered a crux in Thomas Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" (1751), results from a complex manipulation of epitaphic rhetoric."[107] Later, Robert Mack, in 2000, explained that "Gray's Elegy is numbered high among the very greatest poems in the English tradition precisely because of its simultaneous accessibility and inscrutability."[5] He went on to claim that the poem "was very soon to transform his life – and to transform or at least profoundly affect the development of lyric poetry in English".[108] While analyzing the use of "death" in 18th-century poetry, David Morris, in 2001, declared the poem as "a monument in this ongoing transformation of death" and that "the poem in its quiet portraits of rural life succeeds in drawing the forgotten dead back into the community of the living."[109] In 2002, Griffin claimed that the poem was "probably still today the best-known and best-loved poem in English".[110]

See also[]

References[]

- Anonymous (1896), "Academy Portraits: V.--Thomas Gray", The Academy (London: Alexander and Shepheard) 50 (July–December 1896)

- Arnold, Matthew (1881), The English Poets, III, London: Macmillan and Co.

- Benedict, Barbara (2001), "Publishing and Reading Poetry", in Sitter, John, The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Poetry, Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–82, ISBN 978-0521658850

- Bieri, James (2008), Percy Bysshe Shelley, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Bloom, Harold (1987), "Introduction", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Brady, Frank (1987), "Structure and Meaning in Gray's Elegy", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Brooks, Cleanth (1947), The Well Wrought Urn, Harcourt, Brace & World

- Carper, Thomas (1987), "Gray's Personal Elegy", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York:: Chelsea House

- Cazamian, Louis (1957), A History of English Literature: Modern Times, Macmillan (New York) (Trans. W. D. MacInnes and Louis Cazamian)

- Cecil, David (1959), "The Poetry of Thomas Gray", in Clifford, James, Eighteenth Century English Literature, Oxford University Press

- Cohen, Ralph (2001), "The Return to the Ode", in Sitter, John, The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Poetry, Cambridge University Press, pp. 203–224, ISBN 978-0521658850

- Colombo, John (1984), Canadian Literary Landmarks, Hounslow Press

- Cudworth, Charles (1971), "Thomas Gray and Music", The Musical Times 112 (1541 (July 1971)): 646–648, doi:10.2307/957005, http://jstor.org/stable/957005

- Clymer, Lorna (1995), "Graved in Tropes: The Figural Logic of Epitaphs and Elegies in Blair, Gray, Cowper, and Wordsworth", ELH 62 (2 (Summer 1995)): 347–386, doi:10.1353/elh.1995.0011

- Day, Martin (1963), History of English Literature 1660–1837, Garden City: Double Day

- Eliot, T. S. (1932), Seleted Essayslocation=New York, Harcourt Brace

- Fulford, Tim (2001), "'Nature' poetry", in Sitter, John, The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Poetry, Cambridge University Press, pp. 109–132, ISBN 978-0521658850

- Golden, Morris (1988), Thomas Gray, Boston: Twayne Publishers

- Gosse, Edmund (1918), Gray, London: Macmillan and Co.

- Griffin, Dustin (2002), Patriotism and Poetry in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Cambridge University Press

- Haffenden, John (2005), William Empson: Among the Mandarins, Oxford University Press

- Holmes, Richard (1976), Shelley: The Pursuit, London: Quartet Books

- Hough, Graham (1953), The Romantic Poets, London: Hutchinson's University Library

- Hutchings, W. (1987), "Syntax of Death: Instability in Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Johnson, Samuel (1979), Johnson on Shakespeare, Orient Longman

- Johnston, Kenneth (2001), The Hidden Wordsworth, New York: Norton

- Jones, W. Powell (1959), "Johnson and Gray: A Study in Literary Antagonism", TModern Philologys 56 (4 (May, 1959)): 646–648

- Ketton-Cremer, R. W. (1955), Thomas Gray, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Lonsdale, Roger (1973), "The Poetry of Thomas Gray: Versions of the Self", Proceedings of the British Academy (59): 105–123

- Mack, Robert (2000), Thomas Gray: A Life, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08499-4

- Mileur, Jean-Pierre (1987), "Spectators at Our Own Funerals", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Morris, David B. (2001), "A Poetry of Absence", in Sitter, John, The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Poetry, Cambridge University Press, pp. 225–248, ISBN 978-0521658850

- Nicholls, Norton (editor) (1836), The Works of Thomas Gray, London: William Pickering

- Northup, Clark (1917), A Bibliography of Thomas Gray, New Haven: Yale University Press

- Richards, I. A. (1929), Practical Criticism, London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner

- Ryals, Clyde de L. (1996), The Life of Robert Browning, Oxford: Blackwell

- Rzepka, Charles (1986), The Self as Mind, Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- Sacks, Peter (1985), The English Elegy, Johns Hopkins University Press

- Sha, Richard (1990), "Gray's Political Elegy: Poetry as the Burial of History", Philological Quarterly (69): 337–357

- Sherbo, Arthur (1975), English Poetic Diction from Chaucer to Wordsworth, Michigan State University Press

- Sitter, John (2001), "Introduction", in Sitter, John, The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Poetry, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–10, ISBN 978-0521658850

- Smith, Adam (1985), Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund

- Smith, Eric (1987), "Gray: Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Spacks, Patricia (1967), The Poetry of Vision, Harvard University Press

- Starr, Herbert (1968), "Introduction", in Herbert Starr, Twentieth Century Interpretations of Gray's Elegy, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall

- Turner, Paul (2001), The Life of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Blackwell

- Williams, Anne (1987), "Elegy into Lyric: Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Williams, Anne (1984), The Prophetic Strain, University of Chicago Press

- Weinbrot, Howard (1987), "Gray's Elegy: A Poem of Moral Choice and Resolution", in Harold Bloom, Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, New York: Chelsea House

- Wimsatt, W. K. (1970), "Imitations as Freedom", in Reuben Brower, Forms of Lyric, New York: Columbia University Press

- Wright, George (1976), "Eliot Written in a Country Churchyard: The Elegy and the Four Quartets", ELH 42 (2 (Summer 1976)): 227–243

- Young, John (1783), A Criticism on the Elegy Written in a Country Church Yard, London: G. Wilkie

Notes[]

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 143.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 386.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 389.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 385–390.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mack 2000, p. 390.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 391–392.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 393–394, 413–415, 422–423.

- ↑ Quoted in Mack 2000, p. 423.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 423–424.

- ↑ Griffin 2002, p. 167.

- ↑ Cazamian 1957, p. 837.

- ↑ Benedict 2001, p. 73.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Day 1963, p. 196.

- ↑ Northup 1917, pp. 89, 111, 114, 115, 121, 122.

- ↑ Quoted in Mack 2000, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 393–394.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 394–395.

- ↑ Lonsdale 1973, p. 114.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 395–396.

- ↑ Quoted in Mason 2000, p. 396.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 396–397.

- ↑ Smith 1987, pp. 51–52, 65.

- ↑ Sacks 1985, p. 133.

- ↑ Williams 1987, p. 107.

- ↑ Fulford 2001, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 392, 401.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Williams 1984, p. 108.

- ↑ Cohen 2001, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 410.

- ↑ Sherbo 1975, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Bloom 1987, p. 1.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Griffin 2002, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 402.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 402–405.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 405–406.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 406.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 406–407.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 407.

- ↑ Morris 2001, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Sitter 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Williams 1987, p. 109.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 398–400.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 408.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 403–405, 408.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Cecil 1959, p. 241.

- ↑ Cecil 1959, pp. 241–242.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Griffin 2002, p. 164.

- ↑ Griffin 2002, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Sha 1990, pp. 349–352.

- ↑ Spacks 1967, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Griffin 2002, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Hutchings 1987, p. 83.

- ↑ Mileur 1987, p. 119.

- ↑ Johnston 2001, pp. 66, 70.

- ↑ Bieri 2008, pp. 46, 61.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Holmes 1976, p. 293.

- ↑ Sacks 1985, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Ryals 1996, p. 114.

- ↑ Turner 2001, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Wright 1976, pp. 228–332.

- ↑ Mack 2000, pp. 412–413.

- ↑ Quoted in Mack 2000, pp. 412–413.

- ↑ Spacks 1967, p. 90.

- ↑ Nicholls 1836, p. xxviii.

- ↑ Quoted in Colombo 1984, p. 93.

- ↑ Smith 1985, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Quoted in Johnson 1979, p. 51.

- ↑ Quoted in Jones 1959, p. 245.

- ↑ Jones 1959, p. 247.

- ↑ Young 1783, p. 2.

- ↑ Young 1783, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Jones, pp. 247–248.

- ↑ Jones 1959, p. 251.

- ↑ Quoted in Jones 1959, p. 249.

- ↑ Jones 1959, pp. 249–250.

- ↑ Rzepka 1986, p. 66.

- ↑ Turner 2001, p. 164.

- ↑ Arnold 1881, p. 304.

- ↑ Gosse 1918, p. 97.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Gosse 1918, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Anonymous 1896, p. 582.

- ↑ Cazamian 1957, p. 839.

- ↑ Richards 1929, p. 206.

- ↑ Richards 1929, p. 207.

- ↑ Quoted in Haffenden 2005, p. 300.

- ↑ Quoted in Haffenden 2005, p. 301.

- ↑ Eliot 1932, p. 247.

- ↑ Brooks 1947, p. 105.

- ↑ Brooks 1947, p. 121.

- ↑ Ketton-Cremer 1955, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Hough 1953, p. 15.

- ↑ Brady 1987, p. 7.

- ↑ Spacks 1967, p. 115.

- ↑ Spacks 1967, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Starr 1968, p. 9.

- ↑ Wimsatt 1970, p. 156.

- ↑ Cudworth 1971, p. 646.

- ↑ Smith 1987, p. 52.

- ↑ Carper 1987, p. 50.

- ↑ Weinbrot 1987, p. 69.

- ↑ Weinbrot 1987, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Hutchings 1987, p. 98.

- ↑ Williams 1987, p. 101.

- ↑ Bloom 1987, p. 4.

- ↑ Golden 1988, p. 1.

- ↑ Golden 1988, p. 54.

- ↑ Clymer 1995, p. 347.

- ↑ Mack 2000, p. 391.

- ↑ Morris 2001, p. 235.

- ↑ Griffin 2002, p. 149.

External links[]

- Text

- "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard", from The Thomas Gray Archive (University of Oxford)

- Audio / video

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |