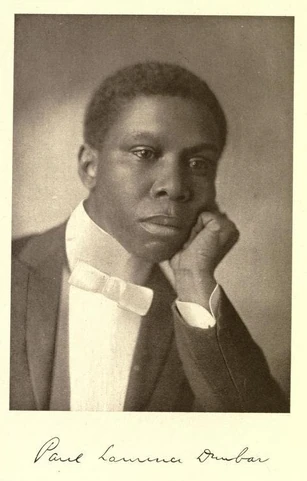

Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), from The Complete Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar, 1913. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Paul Laurence Dunbar (June 27, 1872 - February 9, 1906) was a seminal African-American poet, Dunbar gained national recognition for his 1896 "Ode to Ethiopia", a poem in the collection Lyrics of Lowly Life.

Life[]

Overview[]

Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, on 27 June 1872. He graduated (1891) from the Dayton high school, had a varied experience as elevator boy, mechanic and journalist, and in 1897-1898 held a position on the staff of the Library of Congress, resigning in December 1898 to devote himself to literary work. He died of consumption at his home in Dayton on 8 February 1906. His poetry was brought to the attention of American readers by William Dean Howells, who wrote an appreciative introduction to his Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896). Subsequently Dunbar published 11 other volumes of verse, 3 novels, and 5 collections of short stories.[1]

Some of his short stories and sketches, especially those dealing with the American negro, are charming; they are far superior to his novels, which deal with scenes in which the author is not so much at home. His most enduring work, however, is his poetry. Some of this is in literary English, but the best is in the dialect of his people. In it he has preserved much of their very temperament and outlook on life, usually with truth and freshness of feeling, united with a happy choice of language and much lyrical grace and sweetness, and often with rare humour and pathos. These poems of the soil are a distinct contribution to American literature, and entitle the author to be called pre-eminently the poet of his race in America.[1]

Youth and education[]

Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio to parents who had escaped from slavery in Kentucky. His father was a veteran of the American Civil War, having served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment.

His parents instilled in him a love of learning and history. He was the only African-American student during the years he attended Dayton's Central High School, and he participated actively as a student. During high school, he was both the editor of the school newspaper and class president, as well as the president of the school literary society. He wrote his earliest poem at age 6 and gave his earliest public recital at age 9.

Oak and Ivy[]

Dunbar at age 24, from The Life and Works of Paul Laurence Dunbar, 1907. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 1890 Dunbar wrote and edited Dayton's 1st weekly African-American newspaper, The Tattler, printed by the fledgling company of his high school acquaintances, Wilbur and Orville Wright. The paper lasted only 6 weeks.[2]

In 1892 Dunbar asked the Wrights to publish his dialect poems in book form, but the brothers did not have the means to do so. Dunbar was directed to the United Brethren Publishing House who, in 1893 printed his debut collection of poetry, Oak and Ivy.[2] The work attracted the attention of James Whitcomb Riley, the popular "Hoosier Poet", who like Dunbar wrote poems in both standard English and dialect.

Dunbar's 2nd book, Majors and Minors (1895), brought him national fame and the patronage of William Dean Howells, the novelist, literary critic, and editor of The Atlantic. After Howells' praise, Dunbar's 2 books were printed together as Lyrics of Lowly Life, and Dunbar started on a career of international literary fame. He moved to Washington, D.C., in the LeDroit Park neighborhood. While in Washington, he attended Howard University.

Dunbar maintained a lifelong friendship with the Wrights. He was also associated with Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Brand Whitlock (who was described as a close friend).[3] He was honored with a ceremonial sword by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Later life and work[]

Dunbar wrote a dozen books of poetry, 4 books of short stories, 5 novels, and a play. His essays and poems were published widely in the leading journals of the day. His work appeared in Harper's Weekly, the Saturday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literature, and a number of other publications. During his life, considerable emphasis was laid on the fact that Dunbar was of pure black descent.

Dunbar traveled to England in 1897 to recite his works on the London literary circuit. He met the brilliant young black composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor who set some of his poems to music, and who was influenced by Dunbar to use African and American Negro songs and tunes in future compositions.

After returning from England, Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore in 1898. A graduate of Straight University (now Dillard University) in New Orleans, her most famous works include a sonnet entitled "Violets". She and her husband also wrote books of poetry as companion pieces.

Dunbar took a job at the Library of Congress in Washington. In 1900, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and moved to Colorado with his wife on the advice of his doctors. Dunbar and his wife separated in 1902, but they never divorced.

Dunbar wrote the lyrics for In Dahomey, the 1st all-African-Americans musical to appear on Broadway (in 1903). The musical comedy successfully toured England and America over a period of 4 years.[4]

Depression and declining health drove Dubar to a dependence on alcohol, which further damaged his health. He moved back to Dayton to be with his mother in 1904.

Dunbar died from tuberculosis on February 9, 1906, at age 33.[5] He was interred in the Woodland Cemetery in Dayton.[6]

Writing[]

Dunbar's work is known for its colorful language and use of dialect, and a conversational tone, with a brilliant rhetorical structure. These traits were well matched to the tune-writing ability of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946), with whom he collaborated.[7]

Much of Dunbar's work was authored in standard English, while some was written in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems:

- I am tired, so tired of dialect. I send out graceful little poems, suited for any of the magazines, but they are returned to me by editors who say, Dunbar, but we do not care for the language compositions.

2 brief examples of Dunbar's work, the 1st in standard English and the 2nd in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production:

- What dreams we have and how they fly

- Like rosy clouds across the sky;

- Of wealth, of fame, of sure success,

- Of love that comes to cheer and bless;

- And how they wither, how they fade,

- The waning wealth, the jilting jade —

- The fame that for a moment gleams,

- Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams!

(From "Dreams")

- Sunshine on de medders,

- Greenness on de way;

- Dat's de blessed reason

- I sing all de day.

- Look hyeah! What you axin'?

- What meks me so merry?

- 'Spect to see me sighin'

- W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary?

(From "A warm day in winter")

Recognition[]

Paul Dunbar U.S. postage stamp. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 2002, Molefi Kete Asante listed Paul Laurence Dunbar on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[8]

Places named in his honor include:

- Dunbar High School In various cities

- Dunbar Hospital (Detroit, Michigan)

- Dunbar Magnet Middle School (Little Rock, Arkansas)

- Dunbar Middle School (Lynchburg, Virginia)

- Paul Laurence Dunbar Library (Dayton, Ohio)

- Paul Laurence Dunbar J.H.S 120/M.S. 301 (Bronx, NY)

- Paul Laurence Dunbar Lancaster-Keist Branch Library (Dallas, Texas)

- Dunbar High School (Fort Myers, Florida)

- The Dunbar Hotel (Los Angeles, California)

In popular culture[]

Paul and Alice Dunbar's love and marriage was depicted in a play by Kathleen McGhee-Anderson titled Oak and Ivy.[9]

Dunbar's vaudeville song "Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd" may have influenced the development of "Who Dat?|Who dat? Who dat? Who dat say gonna beat dem Saints?", the New Orleans Saints' chant.[10]

Publications[]

Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), Complete Poems, 1913. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Poetry[]

- Oak and Ivy. United Brethren Publishing House, 1893.

- Majors and Minors: Poems. Hadley & Hadley, 1896.

- Lyrics of Lowly Life (includes poems from Oak and Ivy and Majors and Minors, introduction by William Dean Howells). Dodd, 1896.

- Lyrics of the Hearthside. Dodd, 1899.

- Poems of Cabin and Field (collection of eight previously published poems, illustrated by wife, Alice Morse, photographs by Hampton Institute Camera Club). Dodd, 1899.

- Candle-lightin' Time. Dodd, 1901.

- Lyrics of Love and Laughter. Dodd, 1903.

- When Malindy Sings. Dodd, 1903.

- Li'l Gal. Dodd, 1904.

- Chris'mus Is a Comin', and other poems. Dodd, 1905.

- Howdy, Howdy, Howdy. Dodd, 1905.

- Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow. Dodd, 1905.

- A Plantation Portrait. Dodd, 1905.

- Joggin' Erlong. Dodd, 1906.

- Complete Poems. Dodd, 1913.

- Speakin' o' Christmas, and other Christmas and special poems. Dodd, 1914.

- Little Brown Baby: Poems for young people (edited and with biographical sketch by Bertha Rodgers, illustrated by Erick Berry). Dodd, 1940.

- I Greet the Dawn: Poems (edited and with an introduction by Ashley Bryan). Atheneum, 1978.

- Collected Poetry (edited by Joanne M. Braxton). Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1993.

- Selected Poems. Dover Publications, 1997.

Novels[]

- The Uncalled: A novel. Dodd, 1898.

- The Love of Landry. Dodd, 1900.

- The Fanatics. Dodd, 1901.

- The Sport of the Gods. Dodd, 1902

- (with introduction by Kenny J. Williams), 1981

- published in England as The Jest of Fate: A story of Negro life. Jarrold, 1902.

Short Fiction[]

- Folks From Dixie. Dodd, 1898.

- The Strength of Gideon, and other stories (illustrated by Edward Windsor Kemble). Dodd, 1900.

- In Old Plantation Days (illustrated by B. Martin Justice). Dodd, 1903.

- The Heart of Happy Hollow. Dodd, 1904.

- Best Stories (edited & with introduction by Benjamin Brawley). Dodd, 1938.

Collected editions[]

- Life and Works (edited & with biography by Lida Keck Wiggins). Napierville, IL, & Memphis, TN: J.L. Nichols, 1907.

- The Paul Laurence Dunbar Reader (edited by Jay Martin & Gossie H. Hudson). Dodd, 1975.

Letters[]

- Letters of Paul and Alice Dunbar: A private history (edited by Eugene Wesley Metcalf). (2 volumes), University Microfilms, 1974.

Other[]

- Dream Lovers: An operatic romance (libretto for operetta; music by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor). Boosey, 1898.

- (Author of lyrics) In Dahomey (stage show; music by Will Marion Cook), produced in Boston, then at Buckingham Palace, England, in honor of the birthday of the Prince of Wales, 1903.

- (Contributor) The Negro Problem: A series of articles by representative American Negroes. James Pott, 1903.

- (Contributor) Selected Songs Sung by Students of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. Tuskegee Institute, 1904.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy the Poetry Foundation.[11]

William Warfield recites 3 Paul Laurence Dunbar poems

See also[]

References[]

- Lida Keck Wiggins, The Life and Works of Paul Lawrence Dunbar. Winston-Derek, 1992. ISBN 1-55523-473-9

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Dunbar, Paul Laurence". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 668.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fred Howard (1998). Wilbur and Orville: A Biography of the Wright Brothers. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 560. ISBN 0486402975.

- ↑ Paul Laurence, Printed Material

- ↑ Riis, Thomas L., Just Before Jazz: Black musical theater in New York, 1890-1915. Smithsonian Institution Press: London, 1989, 91. Print.

- ↑ "Biography page at Paul Laurence Dunbar web site". University of Dayton. February 3, 2003. http://www.dunbarsite.org/biopld.asp.

- ↑ "Paul Laurence Dunbar". Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=307. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ↑ The collaboration is described by Max Morath in I Love You Truly: A Biographical Novel Based on the Life of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (New York: iUniverse, 2008), ISBN 9780595530175, p. 17. Morath explicitly cites "The Last Long Rest" and "Poor Little Lamb" (a.k.a. "Sunshine") and alludes to three more songs for which the lyrics are by Dunbar and the music by Jacobs-Bond.

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ↑ St. Louis - Arts & Entertainment - Color Bind

- ↑ Dave Dunbar, The chant is older than we think in Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 2010 January 13, Saint Tammany Edition, pp. A1, A10.

- ↑ Paul Laurence Dunbar 1872-1906, Poetry Foundation, Web, Aug. 26, 2012.

External links[]

- Poems

- Paul Laurence Dunbar 1872-1906 at the Poetry Foundation

- 7 poems by Dunbar: "Summer in the South," "A Summer's Night," "Easter Ode," "October," "In Summer Time," "In Summer," "In August"

- Paul Laurence Dunbar profile & 12 poems at the Academy of American Poets

- Dunbar, Paul Laurence (1872-1906) (12 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- Additional Poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar

- Paul Laurence Dunbar at PoemHunter (424 poems)

- Audio / video

- Paul Laurence Dunbar at YouTube

- Dunbar's Legacy of Language, a 2006 NPR story marking the 100th anniversary of Dunbar's death; included is a poetry reading

- Books

- Works by Paul Laurence Dunbar at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Paul Laurence Dunbar at Internet Archive

- Paul Laurence Dunbar at Amazon.com

- Wright State University's Paul Laurence Dunbar Library special collection

- About

- Paul Laurence Dunbar at NNDB

- Dunbar, Paul Laurence in the Oxford Companion to African-American Literature.

- University of Dayton's Paul Laurence Dunbar web page

- Paul Laurence Dunbar: Online Resources from the Library of Congress

- Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) at Modern American Poetry

- Paul Laurence Dunbar at Find a Grave

- Etc.

- Dunbar House state historical site, by the Ohio Historical Society

- Dunbar house is also part of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park which includes both the Wright Brothers bicycle shop and Dunbar's home (along with a bicycle the Wrights gave him).

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at: Dunbar, Paul Laurence

|