John Dryden (1631-1700). Portrait by James Maubert (1666-1746). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

| John Dryden | |

|---|---|

| Born |

August 9 1631 Aldwincle, Thrapston, Northamptonshire, England |

| Died |

May 1 1700 (aged 68) London, England |

| Occupation | poet, literary critic, playwright= |

| Notable work(s) | Absalom and Achitophel, MacFlecknoe |

|

Influenced

| |

John Henry Dryden (9 August 1631 - 1 May 1700) was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literature of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the "Age of Dryden".[1]

Life[]

Overview[]

Dryden was born at Aldwincle Rectory, Northamptonshire. His father, from whom he inherited a small estate, was Erasmus, 3rd son of Sir Erasmus Driden; his mother was Mary Pickering, also of good family; both families belonged to the Puritan side in politics and religion. He was educated at Westminster School and Cambridge, and thereafter, in 1657, came to London. While at college he had written some not very successful verse. His Heroic Stanzas on the Death of Oliver Cromwell (1658) was his earliest considerable poem. It was followed, in 1660, by Astræa Redux, in honour of the Restoration. The interval of 18 months had been crowded with events, and though much has been written against his apparent change of opinion, it is fair to remember that the whole cast of his mind led him to be a supporter of de facto authority. In 1663 he married Lady Elizabeth Howard, daughter of the Earl of Berkshire. The Restoration introduced a revival of the drama in its most debased form, and for many years Dryden was a prolific playwright. His first effort, The Wild Gallant (1663), was a failure; his next, The Rival Ladies, a tragi-comedy, established his reputation. During the great plague, 1665, Dryden left London, and lived with his father-in-law at Charleton. On his return he published his 1st poem of real power, Annus Mirabilis, of which the subjects were the great fire, and the Dutch War. In 1668 appeared his Essay on Dramatic Poetry in the form of a dialogue, fine alike as criticism and as prose. 2 years later (1670) he became Poet Laureate and Historiographer Royal with a pension of £300 a year. Dryden was now in prosperous circumstances, having received a portion with his wife, and besides the salaries of his appointments, and his profits from literature, holding a valuable share in the King's play-house. In 1671 G. Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, produced his Rehearsal, in ridicule of the overdone heroics of the prevailing drama, and satirising Dryden as Mr. Bayes. To this Dryden made no immediate reply, but bided his time. The next years were devoted to the drama. But by this time public affairs were assuming a critical aspect. A large section of the nation was becoming alarmed at the prospect of the succession of the Duke of York, and a restoration of popery, and Shaftesbury was supposed to be promoting the claims of the Duke of Monmouth. And now Dryden showed; his full powers. The 1st part of Absalom and Achitophel appeared in 1681, in which Charles figures as "David," Shaftesbury as "Achitophel," Monmouth as "Absalom," Buckingham as "Zimri," in the short but crushing delineation of whom the attack of the Rehearsal was requited in the most ample measure. The effect; of the poem was tremendous. Nevertheless the indictment against Shaftesbury for high treason was ignored by the Grand Jury at the Old Bailey, and in honor of the event a medal was struck, which gave a title to Dryden's next stroke. His Medal was issued in 1682. The success of these wonderful poems raised a storm round Dryden Replies were forthcoming in Elkanah Settle's Absalom and Achitophel Transposed, and Pordage's Azaria and Hushai. These compositions, especially Pordage's, were comparatively moderate. Far otherwise was Shadwell's Medal of John Bayes, 1 of the most brutal and indecent pieces in the language. Dryden's's revenge was the publication of MacFlecknoe, Its immediate effect was to crush and silence all his assailants. The following year, 1683, saw the publication of Religio Laici (the religion of a layman). In 1686 Dryden joined the Church of Rome. The change, which was announced by the publication, in 1687 of The Hind and the Panther: A defence of the Roman Church, at all events did not bring with it any worldly advantages. It was parodied by C. Montague andPrior in the Town and Country Mouse. At the Revolution Dryden was deprived of all his pensions and appointments, including the Laureateship, in which he was succeeded by his old enemy Shadwell. His latter years were passed in comparative poverty; in these circumstances he turned again to the drama, which, however, was no longer what it had been as a source of income. To this period belong Don Sebastian, and his last play, Love Triumphant. A new mine, however, was beginning to be opened up in the demand for translations which had arisen. This gave Dryden a new opportunity, and he produced, in addition to translations from Juvenal and Perseus, his famous "Virgil" (1697). About the same time appeared the Ode for St. Cecilia's Day, and Alexander's Feast, and in 1700, the year of his death, the Fables, largely adaptations from Chaucer and Boccaccio. In his own line, that of argument, satire, and declamation, Dryden is without a rival in our literature: he had little creative imagination and no pathos. His dramas, which in bulk are the greatest part of his work, add almost nothing to his fame; in them he was meeting a public demand, not following the native bent of his genius. He seems to have been almost insensible to the beauty of Nature.[2]

Family[]

Dryden was of Cumberland stock, though his family had been settled for 3 generations in Northamptonshire, had acquired estates and a baronetcy, and had intermarried with landed families in that county. His great-grandfather, who originally carried the name south, and acquired by marriage the estate of Canons Ashby, is said to have known Erasmus, and to have been so proud of the great scholar’s friendship that he gave the name of Erasmus to his eldest son. The name Erasmus was also borne by the poet’s father, the 3rd son of Sir Erasmus Dryden.[3]

The leanings and connexions of the family were Puritan and anti-monarchical. Sir Erasmus Dryden went to prison rather than pay loan money to Charles I; the poet’s uncle, Sir John Dryden, and his father Erasmus, served on government commissions during the Commonwealth. His mother’s family, the Pickerings, were still more prominent on the Puritan side. Sir Gilbert Pickering, his cousin, was chamberlain to the Protector, and was summoned to Cromwell’s House of Lords in 1657. A trustworthy tradition asserts that John Dryden was born at the rectory of Aldwinkle All Saints, of which his maternal grandfather, Henry Pickering, was rector.[3]

Youth and education[]

Dryden was born on or about 9 August 1631, at Aldwinkle, in Northamptonshire, the eldest of 14 children,[3]

Dryden’s education was such as became a scion of these respectable families of squires and rectors, among whom the chance contact with Erasmus had left a certain tradition of scholarship. His father (whose own fortune, added to his wife’s, was not large) procured for the poet admission to Westminster School as a king’s scholar, under the famous Dr Busby.[3]

Some elegiac verses which Dryden wrote there on the death of a schoolfellow (Henry, Lord Hastings, son of the earl of Huntingdon) in 1649, were published in Lacrymae Musarum, among other elegies by “divers persons of nobility and worth” in commemoration of the same event. He appeared soon after again in print, among writers of commendatory verses to a friend of his, John Hoddesdon, who published a volume of Epigrams in 1650. Dryden’s contribution is signed “John Dryden of Trinity C.,” as he had gone up from Westminster to Cambridge in May 1650.[3]

He was elected a scholar of Trinity College, Cambridge on the Westminster foundation in October 1650, and earned the degree of B.A. in 1654. The only recorded incident of his college residence is some unexplained act of disobedience to the vice-master, for which he was “put out of commons” and “gated” for a fortnight.[3]

His father died in 1654, leaving him master of 2/3 of a small estate near Blakesley, worth about £60 a year. The next 3 years he is said to have spent at Cambridge.[3]

Early poetry[]

The middle of 1657 is given as the date of his leaving the university to take up his residence in London. In 1 of his many subsequent literary quarrels, it was said by Shadwell that he had been clerk to Sir Gilbert Pickering, his cousin, who was chamberlain to Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector; and nothing is more likely than that he obtained some employment under his powerful cousin when he came to London. He is said to have lived originally in the house of his publisher, Henry Herringman, with whom he was connected till 1679, when Jacob Tonson began to publish his books.[3]

He emerged from obscurity with his Heroic Stanzas (1659) to the memory of the Protector.[3] To those who regard the poet as a seer with a sacred mission, and refuse the name altogether to a literary manufacturer to order, it comes with a certain shock to find Dryden, the hereditary Puritan, the panegyrist of Cromwell, next hailing the return of King Charles in Astraea Redux (1660), deploring his long absence, and proclaiming the despair with which he had seen “the rebel thrive, the loyal crost.” A Panegyric on the Coronation followed in 1661.[3]

Playwright[]

1663-1665[]

Dryden was compelled to supplement his slender income by his writings. He initially thought of tragedy,— his own genius, as he has informed us, inclining him rather to that species of composition; and in the 1st year of the Restoration he wrote a tragedy on the fate of Henry, duke of Guise. But some friends advised him that its construction was not suited to the requirements of the stage, so he put it aside, and used only a scene of the original play later on, when he again attempted the subject with a more practised hand. Having failed to write a suitable tragedy, he next turned his attention to comedy, although, as he admitted, he had little natural turn for it.

His earliest attempt was unsuccessful. Bustle, intrigue and coarsely humorous dialogue seemed to him to be part of the popular demand; and, looking about for a plot, he found something to suit him in a Spanish source, and wrote The Wild Gallant. The play was acted in February 1663, by Thomas Killigrew’s company in Vere Street. It was not a success, and Pepys showed good judgment in pronouncing the play “so poor a thing as ever I saw in my life.” Dryden never learned moderation in his humor; there is a student’s clumsiness and extravagance in his indecency. Of this he seems to have been conscious, for when the play was revived, in 1667, he complained in the epilogue of the difficulty of comic wit, and admitted the right of a common audience to judge of the wit’s success.[3]

His next comedy, The Rival Ladies, also founded on a Spanish plot, produced before the end of 1663, and printed in the next year, was correctly described by Pepys as “a very innocent and most pretty witty play,” though there was much in it which the taste of our time would consider indelicate. But he never quite conquered his tendency to extravagance. The Wild Gallant was not the only victim. The Assignation; or, Love in a nunnery, produced in 1673, shared the same fate; and even as late as 1680, when he had had 20 years’ experience to guide him, The Kind Keeper; or, Mr. Limberham was prohibited, after 3 representations, as being too indecent for the stage. Dislike to indecency we are apt to think a somewhat ludicrous pretext to be made by Restoration playgoers, and probably there was some other reason for the sacrifice of Limberham; still there is a certain savageness in the spirit of Dryden’s indecency which we do not find in his most licentious contemporaries. The undisciplined force of the man carried him to an excess from which more dexterous writers held back.[3]

After the production of The Rival Ladies in 1663, Dryden assisted Sir Robert Howard in the composition of a tragedy in heroic verse, The Indian Queen, produced with great splendor in January 1664. He married Lady Elizabeth Howard, Sir Robert’s sister and daughter of the 1st earl of Berkshire, on the 1st of December 1663. Lady Elizabeth’s reputation was somewhat compromised before this union, which was not a happy one, and there is some evidence for the scandal in a letter written by her before her marriage to Philip, 2nd earl of Chesterfield.[4]

The Indian Queen was a great success, 1 of the greatest since the reopening of the theatres. This was in all likelihood due much less to the heroic verse and the exclusion of comic scenes from the tragedy than to the magnificent scenic accessories — the battles and sacrifices on the stage, the spirits singing in the air, and the god of dreams ascending through a trap. The novelty of these Indian spectacles, as well as of the Indian characters, with the splendid Queen Zempoalla, acted by Mrs Marshall in a real Indian dress of feathers presented to her by Aphra Behn, as the centre of the play, was the chief secret of the success of The Indian Queen. These melodramatic properties were so marked a novelty that they could not fail to draw the town. Dryden was tempted to return to tragedy; he followed up The Indian Queen with The Indian Emperor, or the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, which was acted in 1665, and also proved a success.[4]

During the Great Plague, when the theatres were closed, and Dryden was living at Charlton, Wiltshire, at the seat of his father-in-law, the earl of Berkshire, he occupied a considerable part of his time in thinking over the principles of dramatic composition, and threw his conclusions into the form of a dialogue, which he called an Essay of Dramatick Poesie and published in 1668. Before his return to town at the end of 1666, when the theatres (which had been closed during the disasters of 1665 and 1666) were reopened, Dryden wrote a poem on the Dutch war and the Great Fire entitled Annus Mirabilis.[4]

1666-1670[]

From the reopening of the theatres in 1666 till November 1681, the date of his Absalom and Achitophel, Dryden produced nothing but plays. The stage was his chief source of income. Secret Love; or, The maiden queen, a tragi-comedy, produced in March 1667, was based on an episode in the Artamène, ou le Grand Cyrus of Mlle de Scudéry, the historical original of the “Maiden Queen” being Christina, queen of Sweden. The prologue claims that the piece is written with pains and thought, by the exactest rules, with strict observance of the unities, and “a mingled chime of Jonson’s humour and of Corneille’s rhyme”; but it owed its success chiefly to the charm of Nell Gwyn’s acting in the part of Florimel. It is noticeable that only the more passionate parts of the dialogue are rhymed, Dryden’s theory apparently being that rhyme is then demanded for the elevation of the style.[4]

His next play, Sir Martin Mar-all, or the Feigned Innocence, an adaptation in prose of the duke of Newcastle’s translation of Molière’s L’Étourdi, was produced at the Duke’s theatre, without the author’s name, in 1667. It was about this time that Dryden became a retained writer under contract for the King’s theatre, receiving from it £300 or £400 a year, till it was burnt down in 1672, and about £200 for 6 years more till the beginning of 1678. His co-operation with Davenant in a new version (1667) of Shakespeare’s Tempest — for his share in which Dryden can hardly be pardoned on the ground that the chief alterations were happy thoughts of Davenant’s, seeing that he affirms he never worked at anything with more delight — must also be supposed to be anterior to the completion of his contract with the Theatre Royal. He was engaged to write 3 plays a year, and he contributed only 10 plays during the 10 years of his engagement, finally exhausting the patience of his partners by joining in the composition of a play for the rival house. In adapting L’Étourdi, Dryden did not catch Molière’s lightness of touch; his alterations go towards making the comedy into a farce. Perhaps all the more on this account Sir Martin Mar-all had a great run at the theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.[4]

His An Evening’s Love; or. The mock astrologer, an adaptation from Le Feint Astrologue of the younger Corneille, produced at the King’s theatre in 1668, seemed to Pepys “very smutty, and nothing so good as The Maiden Queen or The Indian Emperor of Dryden’s making.” Evelyn thought it foolish and profane, and was grieved “to see how the stage was degenerated and polluted by the licentious times.” Ladies à la Mode, another of Dryden’s contract comedies, produced in 1668, was “so mean a thing,” Pepys says, that it was only once acted, and Dryden never published it. Of his other comedies, Marriage à la Mode (produced 1672), The Assignation; or, Love in a Nunnery (1673), The Kind Keeper, or Mr. Limberham (1678), only the 1st was moderately successful.[4]

While Dryden met with such indifferent success in his willing efforts to supply the demand of the age for low comedy, he struck upon a really popular and profitable vein in heroic tragedy. Tyrannic Love; or. The royal martyr,[4] a Roman play dealing with the persecution of the Christians by Maximin, in which St. Catherine is introduced, and with her some supernatural machinery, was produced in 1669. It is in rhymed couplets, but the author again did not trust solely for success to them; for, besides the magic incantations, the singing angels, and the view of Paradise, he made Nell Gwyn, who had stabbed herself as Valeria, start to life again as she was being carried off the stage, and speak a riotous epilogue, in violent contrast to the serious character of the play.[5]

Almanzor and Almahide; or the Conquest of Granada, a tragedy in 2 parts, was written in 1669 to 1670. The historical background is taken chiefly from Mlle. de Scudéry’s romance of Almahide, but Dryden borrows freely from other books of hers and her contemporaries. This piece seems to have given the crowning touch of provocation to the wits, who had never ceased to ridicule the popular taste for these extravagant heroic plays. Dryden almost invited burlesque in his epilogue to the 2nd part of The Conquest of Granada, in which he charged the comedy of the Elizabethan age with coarseness and mechanical humour, and its conceptions of love and honour with meanness, and claimed for his own time and his own plays an advance in these respects.[5]

1671-1694[]

The Rehearsal, written by the duke of Buckingham, with the assistance, it was said, of Samuel Butler, Martin Clifford, Thomas Sprat, and others, and produced in 1671, was a severe and just punishment for this boast. Davenant was originally the hero, but on his death in 1668 the satire was turned upon Dryden, who is here unmercifully ridiculed under the name of Bayes, the name being justified by his appointment in 1670 as poet laureate and historiographer to the king (with a pension of £300 a year and a butt of canary wine). It is said that The Rehearsal was begun in 1663 and ready for representation before the plague. But this probably only means that Buckingham and his friends had resolved to burlesque the absurdities of Davenant’s operatic heroes in The Siege of Rhodes, and the extravagant heroics of The Indian Queen. Materials accumulated upon them as the fashion continued, and by the time Dryden had produced his Tyrannic Love and his Conquest of Granada, he had so established himself as the chief offender as to become naturally the central figure of the burlesque.[5]

Later Dryden fully avenged himself on Buckingham by his portrait of Zimri in Absalom and Achitophel. His immediate reply is contained in the preface “Of Heroic Plays” and the “Defence of the Epilogue,” printed in the 1st edition (1672) of his Conquest of Granada. In these, so far from laughing with his censors, he addresses them from the eminence of success. “But I have already swept the stakes; and, with the common good fortune of prosperous gamesters, can be content to sit quietly; to hear my fortune cursed by some, and my faults arraigned by others, and to suffer both without reply.” Heroic verse, he assures them, is so established that few tragedies are likely henceforward to be written in any other metre. In the course of a year or two The Conquest of Granada was attacked also by Elkanah Settle, on whom Dryden revenged himself later, making him the “Doeg” of the 2nd part of Absalom and Achitophel.[5]

His next tragedy, Amboyna (1673), an exhibition of certain atrocities committed by the Dutch on English merchants in the East Indies, put on the stage to inflame the public mind in view of the Dutch war, was written, with the exception of a few passages, in prose, and those passages in blank verse. An opera which he wrote in rhymed couplets, called The State of Innocence, and Fall of Man, an attempt to turn part of Paradise Lost into rhyme, as a proof of its superiority to blank verse, was prefaced by an “Apology for Heroique Poetry and Poetique Licence,” and entered at Stationers’ Hall in 1674, but it was never acted. The redeeming circumstance about the performance is the admiration professed by the adapter for his original, which he pronounces “undoubtedly one of the greatest, most noble and most sublime poems which either this age or nation has produced.” Dryden is said to have had the elder poet’s leave “to tag his verses.”[5]

In Aurengzebe, which was Dryden’s last, and also his best, rhymed tragedy, he borrowed from contemporary history, for the Great Mogul was still living. In the prologue he confessed that he had grown weary of his long-loved mistress rhyme and retracted, with characteristic frankness, his disparaging contrast of the Elizabethan with his own age. But the stings of The Rehearsal had stimulated him to do his utmost to justify his devotion to his mistress, and he claims that Aurengzebe is “the most correct” of his plays. It was entered at Stationers’ Hall and probably acted in 1675, and published in the following year.[5]

After the production of Aurengzebe he seems to have rested for an interval from writing, enabled to do so, probably by an additional pension of £100 granted to him by the king. During this interval he would seem to have reconsidered the principles of dramatic composition, and to have made a particular study of the works of Shakespeare. The fruits of this appeared in All for Love; or. the World Well Lost, a version of the story of Antony and Cleopatra, produced in 1678.[5]

It was 12 years before Dryden produced another tragedy worthy of the power shown in All for Love. Don Sebastian was acted and published in 1690. In the interval, to sum up briefly Dryden’s work as a dramatist, he wrote Oedipus (pr. 1679) and The Duke of Guise (pr. 1683) in conjunction with Nathaniel Lee; Troilus and Cressida (1679); The Spanish Friar (1681); Albion and Albanius, an opera (1685); Amphitryon (1690). In Troilus and Cressida he follows Shakespeare closely in the plot, but the dialogue is rewritten throughout, and not for the better. The versification and the language of the 1st and the 3rd acts of Oedipus, which with the general plan of the play were Dryden’s contribution to the joint work, bear marked evidence of his recent study of Shakespeare. The Duke of Guise provided an obvious parallel with contemporary English politics. Henry III was identified with Charles II, and Monmouth with the duke. The lord chamberlain refused to license it until the political situation was less disturbed.[6]

Dryden’s subsequent plays are not remarkable. Their titles and dates are: King Arthur: An opera (1691), for which Purcell wrote the music; Cleomenes (1692); Love Triumphant (1694).[6]

Satirist[]

Soon after Dryden’s abandonment of heroic couplets in tragedy, he found new and more congenial work for his favourite instrument in satire. As usual the idea was not original to Dryden, though he struck in with his majestic step and energy divine, and immediately took the lead. The pioneer was Mulgrave in his Essay on Satire, an attack on Rochester and the court, which was circulated in MS. in 1679. Dryden himself was suspected of the authorship, and it is not impossible that he gave some help in revising it; but it is not likely that he attacked the king on whom he was dependent for the greater part of his income, and Mulgrave in a note to his Art of Poetry in 1717 expressly asserts Dryden’s ignorance. Dryden, however, was attacked in Rose Street, Covent Garden, and severely cudgelled by a company of ruffians who were generally supposed to have been hired by Rochester. In the same year Oldham’s satire on the Jesuits had immense popularity, chiefly owing to the excitement about the Popish plot.[6]

Dryden took the field as a satirist towards the close of 1681, on the side of the court, at the moment when Shaftesbury, baffled in his efforts to exclude the duke of York from the throne as a papist, and secure the succession of the duke of Monmouth, was waiting his trial for high treason. Absalom and Achitophel produced a great stir: 9 editions were sold in rapid succession in the course of a year.[6]

It is not impossible that the fact that his pension had not been paid since the beginning of 1680 weighed with him in writing this satire to gain the favor of the court. In a play produced in 1681, The Spanish Friar, he had written on the other side, gratifying the popular feeling by attacking the Roman Catholic priesthood.[6]

3 other satires followed Absalom and Achitophel, none of them inferior in point of literary power. The Medall: A satyre against sedition (March 1682) was written in ridicule of the medal struck to commemorate Shaftesbury’s acquittal. Then Dryden had to take vengeance on the literary champions of the Whig party who had opened upon him with all their artillery. Their leader, Shadwell, had attacked him in The Medal of John Bayes, which Dryden answered in October 1682 by Mac Flecknoe; or, A satyr upon the true-blew Protestant poet, T.S. This satire, in which Shadwell filled the title-rôle, served as the model of the Dunciad. To the 2nd part of Absalom and Achitophel (November 1682), written chiefly by Nahum Tate, he contributed a long passage of invective against Robert Ferguson (1 of Monmouth’s chief advisers), Elkanah Settle, Shadwell and others. Religio Laici, which appeared in the same month, though nominally an exposition of a layman’s creed, and deservedly admired as such, was not without a political purpose. It attacked the Papists, but declared the “fanatics” to be still more dangerous.[6]

Catholic[]

On the accession of James II, in 1685, he became a Roman Catholic. There has been much discussion as to whether this conversion was or was not sincere. It can only be said that the coincidence between his change of faith and his change of patron was suspicious, and that Dryden’s character for consistency is certainly not of a kind to quench suspicion. The force of the coincidence cannot be removed by such pleas as that his wife had been a Roman Catholic for several years, or that he was converted by his son, who was converted at Cambridge, even if there were any evidence for these statements. Scott defended Dryden’s conversion,— as Macaulay denounced it, from party motives. It is worth while, however, to notice that in his earlier defence of the English Church he exhibits a desire for the definite guidance of a presumably infallible creed, and the case for the Roman Church brought forward at the time may have appeared convincing to a mind singularly open to new impressions. At the same time nothing can be clearer than that Dryden always regarded his literary powers as a means of subsistence, and had little scruple about accepting a brief on any side.[6]

The Hind and the Panther, published in 1687, is an ingenious argument for Roman Catholicism. It was the chief cause of the veneration with which Dryden was regarded by Pope, who, himself educated in the Roman Catholic faith, was taken as a boy of 12 to see the veteran poet in his chair of honour and authority at Wills’s coffee-house. It was also very open to ridicule, and was treated in this spirit by Prior and Montagu, the future earl of Halifax, in The Hind and the Panther transversed to the story of the Country Mouse and the City Mouse.[6]

Dryden’s other literary services to James were a savage reply to Stillingfleet — who had attacked 2 papers published by the king immediately after his accession, one said to have been written by his late brother in advocacy of the Church of Rome, the other by his late wife explaining the reasons for her conversion — and a translation of a life of Xavier in prose. He had written also a panegyric of Charles, Threnodia Augustalis, and a poem in honour of the birth of James II’s heir, under the title of Britannia Rediviva (1688).[6]

Dryden did not abjure his new faith on the Revolution, and so lost his office and pension as laureate and historiographer royal. For this act of constancy he deserves credit, if the new powers would have considered his services worth having after his frequent apostasies. His rival Shadwell reigned in his stead.[6]

Last years[]

Dryden was once more thrown mainly upon his pen for support. He turned again to the stage and wrote the plays already enumerated. A great feature in the last decade of his life was his translations from the classics.[6] Ovid’s Epistles translated appeared in 1680; and numerous translations from Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Lucretius and Theocritus appeared in the 4 volumes of miscellaneous poems: Miscellany Poems (1684), Sylvae (1685), Examen Poeticum (1693), and The Annual Miscellany (1694 by the “most eminent hands”); in 1693 was published the verse translation of the Satires of Juvenal and of Persius by “Mr Dryden and several other eminent hands,” which contained his “Discourse concerning the Original and Progress of Satire.”[7]

In 1697 Jacob Tonson published his most important translation, The Works of Virgil. The book, which was the result of 3 years’ labour, was a vigorous, rather than a close, rendering of Virgil into the style of Dryden.[7]

His next work was to render some of Chaucer’s and Boccaccio’s tales and Ovid’s Metamorphoses into his own verse. These translations appeared in November 1699, a few months before his death, and are known by the title of Fables: Ancient and modern. The preface, which is an admirable example of Dryden’s prose, contains an excellent appreciation of Chaucer, and, incidentally, an answer to Jeremy Collier’s attack on the stage.[7]

Thus a large portion of the closing years of Dryden’s life was spent in translating for bread. He had a windfall of 500 guineas from Lord Abingdon for a poem on the death of his wife in 1691, and he received liberal presents from his cousin John Driden and from the duke of Ormonde, but generally he was in considerable pecuniary straits. Besides, his 3 sons held various posts in the service of the pope at Rome, and he could not well be on good terms with both courts.[7] However, he was not molested in London by the government, and in private he was treated with the respect due to his old age and his admitted position as the greatest of living English poets. He held a small court at Wills’s coffee-house, where he spent his evenings; here he had a chair by the fire in winter and by the window in summer; Congreve, Vanbrugh and Addison were among his admirers, and here Pope saw the old poet of whom he was to be the most brilliant disciple.[7]

He died at his house in Gerrard Street, London, on the 1st of May 1700 and was buried on the 13th of the month in Westminster Abbey.[7]

Writing[]

Poetry[]

Heroic Stanzas (1659), his first considerable poem, bears indisputable marks of scholarly habits, as well as of a command of verse that could not have been acquired without practice. That the poem should have made him a name as a poet does not appear surprising when we compare them with Waller’s verses on the same occasion. Dryden took some time to consider them, and it was impossible that they should not give an impression of his intellectual strength.Donne was his model; it is obvious that both his ear and his imagination were saturated with Donne’s elegiac strains when he wrote; yet when we look beneath the surface we find unmistakable traces that the pupil was not without decided theories that ran counter to the practice of the master. It is plainly not by accident that each stanza contains one clear-cut brilliant point. The poem is an academic exercise, and it seems to be animated by an under-current of strong contumacious protest against the irregularities tolerated by the authorities. Dryden had studied the ancient classics for himself, and their method of uniformity and elaborate finish commended itself to his robust and orderly mind. In itself the poem is a magnificent tribute to the memory of Cromwell.[3]

From a literary point of view, Astraea Redux (1660) is inferior to the Heroic Stanzas.[3]

Annus Mirabilis (1666) is in quatrains, the same meter as his Heroic Stanzas in praise of Cromwell, which Dryden chose, he tells us, “because he had ever judged it more noble and of greater dignity both for the sound and number than any other verse in use amongst us.” The preface to the poem contains an interesting discussion of what he calls “wit-writing,” introduced by the remark that “the composition of all poems is or ought to be of wit.” His description of the Great Fire is a famous specimen of this wit-writing, much more careless and daring, and much more difficult to sympathize with, than the graver conceits in his panegyric of the Protector. In Annus Mirabilis the poet apostrophizes the newly founded Royal Society.[4]

Dryden’s next poem in heroic couplets was in a different strain. The Hind and the Panther (1687) is an ingenious argument for Roman Catholicism, put into the mouth of “a milk-white hind, immortal and unchanged.” There is considerable beauty in the picture of this tender creature, and its enemies in the forest are not spared. One can understand the admiration that the poem received when such fables were in fashion.[6]

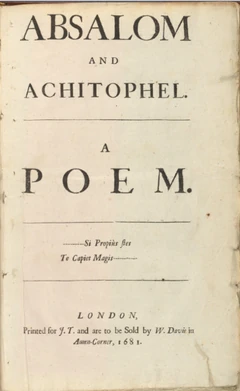

Absalom and Achitophel, 1681. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Soon after Dryden’s abandonment of heroic couplets in tragedy, he found new and more congenial work for his favourite instrument in satire. There was no compunction in Dryden’s ridicule and invective. Delicate wit was not one of Dryden’s gifts; the motions of his weapon were sweeping, and the blows hard and trenchant. The advantage he had gained by his recent studies of character was fully used in Absalom and Achitophel (1681), in his portraits of Shaftesbury and Buckingham, Achitophel and Zimri. In these portraits he shows considerable art in the introduction of redeeming traits to the general outline of malignity and depravity.[6] MacFlecknoe (1682) is a satire in which all his opponents, but especially Thomas Shadwell, were held up to the loathing and ridicule of succeeding ages, and others had conferred, upon them an immortality which, however unenviable, no efforts of their own could have secured for them. In his satires, and in such poems as Alexander's Feast, Dryden rises to the highest point of his powers in a verse swift and heart-stirring.[2]

Among other notable poems of his last years are the 2 “Songs for St Cecilia’s Day,” written for a London musical society for 1687 and 1697, and published separately. The 2nd of these is the famous ode on “Alexander’s Feast.” The well-known paraphrase of Veni, Creator Spiritus was posthumously printed, and his “Ode to the memory of Anne Killigrew,” called by Johnson the noblest ode in the language, was written in 1686.[7]

Dryden's heroic couplet became the dominant poetic form of the 18th century. The most influential poet of the 18th century, Pope, was heavily influenced by Dryden, and often borrowed from him; other writers were equally influenced by Dryden and Pope. Pope famously praised Dryden's versification in his imitation of Horace's Epistle II.i: "Dryden taught to join / The varying pause, the full resounding line, / The long majestic march, and energy divine." Samuel Johnson summed up the general attitude with his remark that "the veneration with which his name is pronounced by every cultivator of English literature, is paid to him as he refined the language, improved the sentiments, and tuned the numbers of English poetry."[8] His poems were very widely read, and are often quoted, for instance, in Tom Jones and Johnson's essays.

Plays[]

Dryden was a prolific playwright, but though his vigorous powers enabled him to work effectively in this department, as in every other in which he engaged, it was not his natural line, and happily his fame does not rest upon his plays, which are deeply stained with the immorality of the age.[2]

He was really as well as ostentatiously a playwright; the age demanded comedies, and he endeavoured to supply the kind of comedy that the age demanded. “I confess,” he said, in a short essay in his own defence, printed before The Indian Emperor,

- my chief endeavours are to delight the age in which I live. If the humour of this be for low comedy, small accidents and raillery, I will force my genius to obey it, though with more reputation I could write in verse. I know I am not so fitted by nature to write comedy; I want that gaiety of humour which is required to it. My conversation is slow and dull; my humour saturnine and reserved; in short, I am none of those who endeavour to break jests in company or make repartees. So that those who decry my comedies do me no injury, except it be in point of profit; reputation in them is the last thing to which I shall pretend.[3]

There is always a certain coarseness in Dryden’s humour, apart from the coarseness of his age,— a certain forcible roughness of touch which belongs to the character of the man.[4]

All for Love (1678) must be regarded as a very remarkable departure for a man of his age, and a wonderful proof of undiminished openness and plasticity of mind. In his previous writings on dramatic theory, Dryden, while admiring the rhyme of the French dramatists as an advance in art, did not give unqualified praise to the regularity of their plots; he was disposed to allow the irregular structure of the Elizabethan dramatists, as being more favourable to variety both of action and of character. But now, in frank imitation of Shakespeare, he abandoned rhyme, and, if we might judge from All for Love and the precepts laid down in his “Grounds of Criticism in Tragedy,” prefixed to Troilus and Cressida (1679), the chief point in which he aimed at excelling the Elizabethans was in giving greater unity to his plot. He upheld still the superiority of Shakespeare to the French dramatists in the delineation of character, but he thought that the scope of the action might be restricted, and the parts bound more closely together with advantage.[5]

All for Love and Antony and Cleopatra are 2 excellent plays for the comparison of the methods. Dryden gave all his strength to All for Love, writing the play for himself, as he said, and not for the public. Carrying out the idea expressed in the title, he represents the 2 lovers as being more entirely under the dominion of love than Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. Shakespeare’s Antony is moved by other impulses than the passion for Cleopatra; it is his master motive, but it has to maintain a struggle for supremacy; “Roman thoughts” strike in upon him even in the very height of the enjoyment of his mistress’s love, he chafes under the yoke, and breaks away from her of his own impulse at the call of spontaneously reawakened ambition. Dryden’s Antony is so deeply sunk in love that no other impulse has power to stir him; it takes much persuasion and skilful artifice to detach him from Cleopatra even in thought, and his soul returns to her violently before the rupture has been completed. On the other hand, Dryden’s Cleopatra is so completely enslaved by love for Antony that she is incapable of using the calculated caprices and meretricious coquetries which Shakespeare’s Cleopatra deliberately practises as the highest art of love, the surest way of maintaining her empire over her great captain’s heart. It is with difficulty that Dryden’s Cleopatra will agree, on the earnest solicitation of a wily counsellor, to feign a liking for Dolabella to excite Antony’s jealousy, and she cannot keep up the pretence through a few sentences. The characters of the two lovers are thus very much contracted, indeed almost overwhelmed, beneath the pressure of the one ruling motive. And as Dryden thus introduces a greater regularity of character into the drama, so he also very much contracts the action, in order to give probability to this temporary subjugation of individual character.[5]

The action of Dryden’s play takes place wholly in Alexandria, within the compass of a few days; it does not, like Shakespeare’s, extend over several years, and present incessant changes of scene. Dryden chooses, as it were, a fragment of a historical action, a single moment during which motives play within a narrow circle, the culminating point in the relations between his 2 personages. He devotes his whole play, also, to those relations; only what bears upon them is admitted. In Shakespeare’s play we get a certain historical perspective,[5] in which the love of Antony and Cleopatra appears in its true proportions beneath the firmament that overhangs human affairs. In Dryden’s play this love is our universe; all the other concerns of the world retire into a shadowy, indistinct background. If we rise from a comparison of the plays with an impression that the Elizabethan drama is a higher type of drama, taking Dryden’s own definition of the word as “a just and lively image of human nature,” we rise also with an impression of Dryden’s power such as we get from nothing else that he had written since his Heroic Stanzas, 20 years before.[6]

The plot of Don Sebastian is more intricate than that of All for Love. It has also more of the characteristics of his heroic dramas; the extravagance of sentiment and the suddenness of impulse remind us occasionally of The Indian Emperor; but the characters are much more elaborately studied than in Dryden’s earlier plays, and the verse is sinewy and powerful. It would be difficult to say whether Don Sebastian or All for Love is his best play; they share the palm between them.[6]

Prose[]

In prose Dryden's style is clear, strong, and nervous.[2]

The Essay of Dramatick Poesie (1668) takes the form of a dialogue between Neander (Dryden), Eugenius (Charles, Lord Buckhurst, afterwards earl of Dorset), Crites (Sir R. Howard), and Lisideius (Sir Charles Sedley), who is made responsible for the famous definition of a play as a “just and lively image of human nature, representing its passions and humours, and the changes of fortune to which it is subject, for the delight and instruction of mankind.” Dryden’s form is of course borrowed from the ancients, and his main source is the critical work of Corneille in the prefaces and discourses contained in the edition of 1660, but he was well acquainted with the whole body of contemporary French and Spanish criticism. Crites maintains the superiority of the classical drama; Lisideius supports the exacting rules of French dramatic writing; Neander defends the English drama of the preceding generations, including, in a long speech, an examination of Ben Jonson’s Silent Woman. Neander argues, however, that English drama has much to gain by the observance of exact methods of construction without abandoning entirely the liberty which English writers had always claimed. He then goes on to defend the use of rhyme in serious drama.[4]

Howard had argued against the use of rhyme in a “preface” to Four New Plays (1665), which had furnished the excuse for Dryden’s essay. Howard replied to Dryden’s essay in a preface to The Duke of Lerma (1668). Dryden at once replied in a masterpiece of sarcastic retort and vigorous reasoning, A Defence of an Essay of Dramatique Poesie, prefixed to the 2nd edition (1668) of The Indian Emperor. It is the ablest and most complete statement of his views about the employment of rhymed couplets in tragedy.[4]

Critical introduction[]

Dryden has been called the greatest writer of a little age; but it may well be doubted whether he for one would have cared to accept either limb of the antithesis. None of his moral qualities better consorted with his magnificent genius than the real modesty which underlay his buoyant self-assertion. His attitude towards the great literary representative of an age earlier than that to which his own maturity belonged was from first to last one of reverent recognition; and though the lines written by Dryden under Milton’s portrait have more sound than point, they should not be forgotten as testifying to the spirit which dictated them.

Of Oldham, in both the species of verse to which he owed his reputation infinitely Dryden’s inferior, the elder poet wrote that their souls were near allied, and cast in the same poetic mould. To Congreve, his junior by full 40 years, he declared that he would gladly have resigned the laureateship, in which he had been supplanted by a Whig poetaster. On the other hand, whatever aspect the Restoration age, either in politics or in literature, may wear in our eyes, in its own it assumed any semblance rather than that of an age of decline. And indeed, to speak of its literature only, it must be admitted that there are not a few considerations to be urged against the acceptance of such a designation.

It is common enough to find the literature of the Restoration age set down as essentially a foreign literature, reproduced and imitated. Yet a survey of Dryden’s works alone, both dramatic and non-dramatic, should suffice to shake the foundations of any such criticism. The "heroic plays" — a species in which Dryden had rivals but no equal — differed from the courtly romances of the Scudéry school as full-bodied Burgundy differs from diluted claret. The so-called Restoration comedy — of the later and more perfect growth of which Dryden’s efforts were but the precursors — is both for better and for worse as genuinely national as it is unmistakeably real.

It would of course be extremely absurd to deny the great influence in this period of French literature upon our own; but it was an influence of much greater importance for the future of our literature, both prose and verse, as to form than as to matter. Yet though the clearness as well as the pointedness of the Restoration style was partly due to French example, these qualities were something very different from the imported fashions of a season. Dryden may be charged with more than his usual audacity when, in a Prologue of 1672, he spoke of "our wit" as far excelling "foreign wit," after, in an Epilogue of 1670, he had extolled his own times as not only wittier but "more refined and free" in their use of the native tongue than any preceding age. Yet inasmuch as during 2 centuries English writers have on the whole followed Dryden and his contemporaries instead of reverting to their predecessors of the Elizabethan and earlier Stuart periods, it would savour of rashness contemptuously to dismiss the claims to literary honors of an age which formed for itself a style of so proved a merit. With the aid of this style it virtually called into life a new species of English poetry — that satirical poetry of which Dryden is not indeed the originator, but in which he was the first as he has in most respects remained the greatest master.

Whatever view be taken of the general features of the age of which Dryden was the chief literary ornament — while Milton’s muse, like the blind poet himself, dwelt apart — it is certain that this age speaks to us from the pages of its most brilliant writer. He was not formed, as a man or as a poet, to live out of his times. Yet neither was he, in character or in genius, one of those who merely give back what they have received, more or less changed in form or intensified in manner. He has been decried as a time-server in politics, as a turncoat in religion, and in literature as the flexible follower of a succession of schools. The reasons for and against these charges cannot be examined here; and there seems something specially unsuitable in treating of Dryden in a tone of apology.

At the same time both his life and works, the relations between which are peculiarly intimate, often require to be protected from some of the commentaries with which they have been visited. Many of our poets have been subjected to ungenerous criticism; but none has, so to speak, been "hansardised" so mercilessly as Dryden.

He was the descendant of Puritan ancestors on both the father’s and the mother’s side; his own father — according to an adversary of the poet’s — was a Committee-man, and one of his maternal cousins was a peer of Oliver’s creation. Nothing could therefore be more natural or becoming than that on the Protector’s death, Dryden, then a young man of 27, should have sung the praises of ‘our Prince,’ generally selecting for celebration qualities which even Cromwell’s angriest enemies would not have denied him to have possessed.

That the author of the Heroic Stanzas should with the Restoration have blossomed forth as a royalist implies no tergiversation at all. It should not be forgotten that the Restoration was not a mere party act; and that much had happened between it and the death of Oliver Cromwell. Whatever may have been the hereditary politics of Dridens and Pickerings, John Dryden was a born royalist, and with the Restoration his political changes were at an end.

Panegyrical poetry was the fashion of the age, and the exuberant inventiveness and felicitous readiness of Dryden’s genius made it easy for him to excel in this kind of composition. To be sure, even the most willing and the most fluent muse must rapidly exhaust such a theme as the virtues of King Charles II; and in his Threnodia Augustalis, written on the King’s death, Dryden found little to add to what he had sung in the Astræa Redux, composed in honour of the Restoration,— except that his Majesty died hard. In shorter pieces in honour of the King, the Duchess of York, and Lord Clarendon, Dryden displayed the same talent for waving gorgeous banners of courtly praise, till in Britannia Rediviva he hailed the birth of a prince whom half the nation regarded as a pretender before he and his parents were exiles.

No laureate has ever earned like Dryden the butt of sack which the economy of King James’ new reign cut off from his salary. Of all the tours de force executed by him, however, the most extraordinary is that in which he undertook to flatter the nation, as well as the dynasty, to the top of their bent. The fire and spirit of the Annus Mirabilis are nothing short of amazing, when the difficulties which beset the author (though partly by his own choosing) are remembered. There was, first, the difficulty of his subject, which, as a perusal of the poem cannot fail to reveal to the most unsuspecting reader, was by no means made up altogether of materials for congratulation. Yet the Annus Mirabilis must really have ‘done good’ to the public; even at the present day it agreeably warms the John Bull sentiment, compounded of patriotism and prejudice, in the corner of an Englishman’s heart.

Another difficulty, but in this instance a self-imposed one, was the form of verse in which the poem was written. It was chosen for the sake of its dignity, but (as Dryden well knew, and told Davenant, from whose Gondibert it was borrowed) it put a far greater strain upon the ingenuity and skill of the author. Thus though Dryden has written much that is more thoroughly enjoyable, he has written nothing that is more characteristic of himself than this long series of quatrains. The glorious dash of the performance is his own, and so is the victorious struggle against the drag of a difficult and rather dull meter.

But it was a yet different kind of poem by which the loyal adherent of the Stuart throne first became a force in English politics. No modern reader, whether his sympathies be with the Jebusites, or whether he think that there may be something to be said even in favour of the Solymæan rout, is likely to refuse his admiration to the greatest — greatest without even a suggestion of rivalry — of English political satires. This position in a literature rich in contributions of the same kind to political controversy Absalom and Achitophel (or rather the First Part of the satire) owes to the reason which made it so singularly effective at the season of its publication. Besides being executed with incomparable vigour and verve, and as finished in detail as it is impetuous in flow, it has the supreme merit (for a work of this kind) of being completely adapted to its special purpose.

Absalom and Achitophel is a political satire pure and simple, not, like Hudibras, a burlesque on a whole cauldron-full of political and religious controversy. The allegorical form of the satire, while so familiar in itself as to save all trouble in guessing the author’s enigmas, just suffices for veiling the real theme beneath a decent disguise; but it by no means interferes with a quality necessary for the effectiveness of the work — its directness. Accordingly, every shaft flies home; in every character, from Achitophel and Zimri to the lesser which are as it were merely touched in passing, precisely those features are marked as to which it is desirable to strengthen and sharpen the suspicions of the popular instinct. The object of the writer being, not to furnish a satirical narrative of a complete historical episode, but to give a striking picture of the influences which had led to the situation existing at the time when Shaftesbury was to be placed on his trial for treason, the real completion of the plot of the poem would have been furnished by the event which it was designed to bring about — namely the conviction and condemnation of its treacherous hero.

Thus, the First Part combines with its vehement invective and fervent enthusiasm a moderation proving the author’s hand to be that of a shrewd as well as a keen politician. The blows are not dealt indiscriminately, as in an Aristophanic comedy to which nothing is sacred, or in the wantonness of partisan wit, such as Canning poured forth against the impotence he disliked not less than against the fanaticism he abhorred,— but with care and even with self-restraint. Absalom (Monmouth) is "lamented" rather than "accused"; even Achitophel himself where he deserves praise receives it from the candour of his politic assailant. When Dryden revised the poem for a second edition, he was least of all anxious to sharpen the sting of incidental passages; for his purpose had not been to vilify all the opponents of the Court, but to ensure the downfall of the false Achitophel, who was first among them all.

Johnson has commended Dryden’s Absalom and Achitophel as "comprising all the excellences of which the subject is capable"; and not a jot need be abated from this at once high and judicious encomium. In what other poem of the kind will be found, together with so much versatility of wit, so incisive a directness of poetic eloquence? Dryden is here at his best; and being at his best, he is entirely free from that irrepressible desire to outdo himself, which in a great author as in a great actor so greatly interferes with our enjoyment of his endeavours, and to which in productions of a different kind Dryden often gave way. This self-control was the more to his credit, since he had not yet shot all the bolts in his quiver, and declared himself quite prepared to convince those who thought otherwise ‘at their own cost, that he could write severely with more ease than he could write gently.’

The successors and the sequel, however, to the First Part of Absalom and Achitophel have the diminished fire of polemics composed after the crisis is over. The pungent satire of The Medal, written after the throwing out of the bill of indictment against Shaftesbury by the London grand jury, ridicules the hypocrisy of the hero of the Puritan Londoners, and the sovereign stupidity of his worshippers, the mob—a stupidity against which ‘even gods contend in vain’:

- ‘Almighty crowd! thou shortenest all dispute;

- Power is thy essence, wit thy attribute!

- Nor faith nor reason make thee at a stay:

- Thou leap’st o’er all eternal truths in thy Pindaric way.’

The last line, by the way, reminds us indirectly of one of Dryden’s favourite metrical devices—unfortunately too frequently and too indiscriminately employed by him—the incidental Alexandrine.) Among the Whig writers who took upon themselves to reply to The Medal, was Thomas Shadwell, ‘the true-blue poet,’—who was afterwards to supersede Dryden as laureate, and who as a comic dramatist displays a measure of power which makes it necessary to take exception to the sweeping contemptuousness of Dryden’s satire against him.

Shadwell is the hero of Mac Flecnoe, to which brilliant but not very generous jeu d’esprit a harmless scribbler (who had even to the best of his ability extolled Dryden himself) was made to give his name. This most happily executed retort upon a by no means despicable antagonist has a double claim to immortality:—its own delightful execution, and the fact that this attempt to extinguish a single Dunce suggested to Pope the heroic idea of annihilating the whole tribe.

The list of Dryden’s satirical poetry closes with his contributions to the Second Part of Absalom and Achitophel, of which Nahum Tate (afterwards Poet-Laureate in his turn) was the principal author. Tate’s muse might well wax faint in striving to raise her own feeble efforts to the level of ‘the song of Asaph’; nor will his name be linked by posterity with Dryden’s as it is with Brady’s. The characters of Og (Shadwell) and Doeg (Elkanah Settle, the city poet, whose political opinions changed more than once, without landing him in a competency at the end) are in Dryden’s most successful, and in his most rollicking, manner.

Thus, in what were at once the earliest and among the bitterest days of modern English party life, the court poet had thrown himself heart and soul into the conflict, and had constituted himself the chief literary champion of a side which in any case must have engaged his goodwill and sympathy. At home and abroad, the adversaries of the Stuarts were the natural objects of his satire; for how could a born partisan of centralised authority love either Dutchmen or Dissenters? It would be hard to say which he attacked with greater zest, whenever opportunity arose. His attempt to inflame popular sentiment against the Dutch in the sensation drama of Amboyna is a disgraceful illustration of too common a misgrowth of patriotism. Even in the pleasant Epistle which quite at the close of his life he addressed to his kinsman, and which he himself considered as well written as anything he had ever composed, he had originally introduced some reflexions on Dutch valour, though a Dutchman sat on the throne. His antipathy against the Nonconformists he was to exhibit under circumstances creditable at all events to the ingenuousness of his partisanship.

The history of Dryden’s religious opinions has called forth very various and much cruel comment. All that is possible on the present occasion is to suggest, as indispensable to any enquiry into the process and motives of Dryden’s conversion to the Church of Rome, a candid and impartial examination of his two poems, the Religio Laici (published in November 1682) and The Hind and the Panther (April 1687). In his most amusing comedy of The Spanish Friar (1681) it is difficult to discover anything bearing on the subject beyond evidence that Dryden hated priests,—a feeling to which he steadily adhered even after he had become a member of the Church of Rome.

There is nothing whatever to show that the Religio Laici was called forth by any special occasion, or juncture of circumstances, in the life of its author. Nor can it be looked upon as the declaration of any creed in particular; for there are surely few members of any Protestant Church who would care to accept the Layman’s exposition of his standpoint as a summary of their beliefs. Unwilling to take refuge in natural religion, unable to accept the theory of an infallible Church, and resenting the practice of leaving the truth revealed in the Bible at the mercy of the rabble, the Layman is content to bow to authority where it deserves the name, to leave obscure points aside, and where he cannot agree with the Church, to waive his private judgment for the sake of peace:

- ‘For points obscure are of small use to learn,

- But common quiet is the world’s concern.’

That a Protestant whose Protestantism stood on so very weak a footing should have been led after all into the bosom of a Church claiming infallibility, seems a fact easily accounted for; and in truth the Religio Laici might almost be called a halfway-house in the road along which Dryden was travelling. A reverence for authority was implanted in his nature; he was a Tory before he was a Catholic; moreover, he was at no time a man to strain at minor difficulties; and it was therefore almost inevitable that the Layman’s simple Creed would sooner or later cease to satisfy a mind inclined and accustomed to look at things in the grand style.

If, in point of fact, this time came very soon, there is no reason to deny that events happening and currents in operation around him, may have hastened the change. There are seasons specially favourable for a roll-call in the moral as in the political world; and apart from the bias in his mind, Dryden was probably not one of the converts whom Rome has found it most difficult to secure. But to attribute his conversion to the renewal of a trumpery pension—whether granted immediately before or just after his declaration of his change of faith—is not less ignoble than it is idle vaguely to suggest that he was influenced by ‘visions of greater worldly advantage.’ If his conversion finds sufficient explanation as a process natural to a mind and disposition constituted like his, and subjected to the general influences of an age like that in which he lived, there remains no controversy to be discussed.

That after becoming a Roman Catholic he should have felt a strong desire to offer to the world a defence of a position not new to the world, but new and therefore in a sense uneasy to himself, seems quite in accordance with experience. But that The Hind and the Panther was not published in order to conciliate the favour of King James II, is manifest from a very noteworthy circumstance. This poem, a species of eirenicon (as it might almost be called) to the Church of England on behalf of the Church of Rome, and an invitation to the former to unite with the latter against the Nonconformists, appeared a fortnight after the Declaration of Indulgence, by which the king had sought to conciliate the support of ‘the Bear, the Boar and every savage name’ willing to listen to the voice of the charmer.

The Hind and the Panther has been censured by critics and burlesqued by wits on account of the supposed incongruity of its characters and dialogue. But there is no reason why beasts should not talk theology or politics — or anything else under the sun — in a piece constructed not as an allegory, but as a fable; and moreover, as Sir Walter Scott has pointed out, Dryden might have appealed for precedents to the works of both Chaucer and Spenser. The lengthiness of parts of the poem may at the same time be undeniable; but its wit and vigour of expression, aided by a versification which Pope declared to be the most correct to be found in Dryden, render it a unique contribution to controversial literature. That the author of The Hind and the Panther had lost little, if any, of his power as a satirist, will be evident from some of the passages cited below as being more suitable for extraction than snatches of controversy—the description of the Nonconformist sects, the character of Father Petre (judiciously put into the Panther’s lips) and that of Dr. (afterwards Bishop) Burnet, whom Dryden had already attacked in passing as Balak in Absalom and Achitophel, and who replied in his History of his own Time by stigmatizing Dryden as ‘a master of immodesty and impurity of all sorts.’

This retort, or the element of truth contained in its violence, cannot be waved aside like the charges brought against Dryden of political and religious dishonesty. The licentiousness of the Restoration drama, which it would have mightily amused the Restoration dramatists to see explained as mere imaginative frolicsomeness, found in him a too willing representative, to be distinguished from the rest only because he had a genius to pervert and to profane. But it should be remembered in his honour that though he was not strong enough to resist temptation, he was true enough to his nobler self to feel and to record the degradation of his weakness. Posterity need utter no severer censure on one who has spoken of his ‘second fall’ with the solemn severity of self-knowledge displayed by Dryden in the incomparably beautiful Ode to the Memory of Anne Killigrew. His nature was too fine and too manly petulantly to defy any criticism which he thought in any measure just, although he might deprecate exaggerated rigour, and despise a preciseness of censure which to men of his mould is virtually unintelligible.

Undoubtedly, though the strength and pointedness of his style makes him recognisable in almost everything he has written—a Hercules truly to be guessed from a mere bit of himself—Dryden is one of those authors to whom complete justice can never be done by those who study him in selections only. The inexhaustible fertility and grandiose ease of his style require the vast expanse of his collected works for their full display. But what cannot be exhibited in completeness, may be indicated by contrast.

Truly great as a satirical, and unusually effective as a didactic poet, Dryden as an ode-writer surpassed even Cowley in execution, and at times equalled him in felicity of conception. From the panegyrical strains of his earlier days he passed in his later to a twofold treatment of a theme not less difficult and far loftier than the praise of earthly crowns and their wearers. The two famous lyrics in honour of St. Cecilia’s Day are almost equally brilliant in execution; but the earlier and shorter is not altogether successful in avoiding the dangers incidental to any attempt of a more elaborate kind to make ‘the sound appear an echo to the sense.’ Alexander’s Feast, on the other hand, may not be without a certain operatic artificiality; but affectation alone can pretend to be insensible to the magnificent impetus of its movement, or to the harmonious charm of its finale.

Of Dryden’s art as a translator only one example could find a place here — the simple but singularly powerful version, familiar to many generations, of the "Veni, Creator Spiritus." Yet this kind of literary work was one which neither he nor his contemporaries were inclined to undervalue. He possessed one of two qualities essential to a master in translation, and lacked the other. While gifted with an almost instinctive power of seizing upon the salient points in his original, and wonderfully facile in rendering these by ingenious turns of thought and phrase in his own tongue, he had neither the nature nor the training of a scholar. He is accordingly at once the most felicitous and the most reckless of English poetic translators.

His modernisations of Chaucer, which with translations from Homer, Ovid, and Boccaccio made up his last publication, the Fables, show his mastery over his form at least as strikingly as any other of his works. In the days in which we live Dryden’s long popular re-castings of Chaucer happily can receive no other praise than this. But something more than a mere shred of purple seemed required by way of example of these famous ‘translations’ by one great English poet of another and greater.

As a dramatist he cannot here be discussed; but room has been found for an example of one or two of his Prologues and Epilogues, in which the poet, following the fashion of his times, converses at his ease with his public through the medium of a favourite actor — or (since King David’s happy restoration) of a favourite actress. But nowhere do the wit and the "frankness" of the age (to use the term applied to it by one of its most popular comedians) find readier expression than in these sallies of badinage, occasionally intermixed with a grain of salt satire, or doing duty as acrid invective or patriotic bluster; and nowhere is the genial freespokenness of Dryden more thoroughly at home than in these confidences between dramatist and public.

Lastly, it should not be forgotten that as a prose critic of dramatic poetry and its laws Dryden remains much more than readable at the present day; his inconsistencies any tyro can point out, but it is better worth while to appreciate the force of much that he says on whatever side of a question he may advocate. Among all our poets few have found better reasons for their theories, or for the practice they have based on the theories of others.

In Dryden it is futile to seek for poetic qualities which he neither possessed nor affected. Wordsworth remarked of him that there is not "a single image from nature in the whole body of his works." One may safely add to this, that he is without lyric depth, and incapable of true sublimity—a quality which he revered in Milton. If it be too much to say that the magnificent instrument through which his genius discourses its music lacks the vox humana of poetry speaking to the heart, the still rarer presence of the vox angelica is certainly wanting to it.

But he is master of his poetic form — more especially of that heroic couplet to which he gave a strength unequalled by any of his successors, even by Pope, who surpassed him in finish. And if there is grandeur in the pomp of kings and the march of hosts, in the "trumpet’s loud clangour" and in tapestries and carpetings of velvet and gold, Dryden is to be ranked with the grandest of English poets. The irresistible impetus of an invective which never falls short or flat, and the savour of a satire which never seems dull or stale, give him an undisputed place among the most glorious of English wits.[9]

Recognition[]

He was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1662.[4]

Dryden was appointed Poet Laureate in 1668 and historiographer royal in 1670, but was removed from both positions in 1689 following the Glorious Revolution.

Dryden was buried in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey. A monument, designed by James Gibbs, was erected in 1720. Dryden's bust on the monument was replaced in 1731.[10]

Many years after his death a house at Westminster School was founded in his name.

6 of his poems ("Ode," "A Song for St. Cecilia's Day, 1687," "Ah, how sweet it is to love!", "Hidden Flame," "Song to a Fair Young Lady, going out of the Town in the Spring," and "Lament of the Irish Emigrant") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[11]

Dryden’s portrait, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, is in the National Portrait Gallery.[7]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Astraea Redux: A poem on the happy restoration and return of his sacred majesty Charles the Second. London: J.M. for Henry Herringman, 1660.

- To His Sacred Majesty: A panegyrick on his coronation. London: Henry Herringman, 1661.

- Annus Mirabilis: The year of wonders, 1666. London: Henry Herringman, 1667.

- Absalom and Achitophel. London: Printed for J.T. & sold by W. Davis, 1681.

- The Medall: A satyre against sedition. London: Jacob Tonson, 1682.

- Mac Flecknoe; or, A satyr upon the true-blew Protestant poet T.S. [unauthorized edition]. London: D. Green, 1682.

- Religio Laici; or, A laymans faith. London: Jacob Tonson, 1682.

- Miscellany Poems. London: Jacob Tonson, 1684. Volume II, Volume IV, Volume VI

- Threnodia Augustalis: A funeral-pindarique poem sacred to the happy memory of King Charles II. London: Jacob Tonson, 1685.

- The Hind and the Panther. London: Jacob Tonson, 1687.

- A Song for St Cecilia's Day, 1687 (with music by Giovanni Baptista Draghi). London: T. Dring, 1687.

- Britannia Rediviva: A poem on the birth of the Prince. London: Jacob Tonson, 1688.

- Eleonora: A panegyrical poem dedicated to the memory of the late Countess of Abingdon. London: Jacob Tonson, 1692.

- An Ode: On the death of Mr. Henry Purcell; late servant of his Majesty, and organist of the Chapel Royal, and of St. Peter's Westminster. London: J. Heptinstall for Henry Playford, 1696.

- Alexander's Feast; or, The power of musique: An ode in honour of St. Cecilia's Day. London: Jacob Tonson, 1697.

- Original Poems and Translations. London: J. & R. Tonson, 1743. Volume I

- The Poetical Works. London: William Pickering, 1852. Volume I, Volume III

- Poetical Works (edited by Rev. George Gilfillan). London: Ballantyne & Co., 1855. Volume I; Volume II.[12]

- Poetical Works. New York: Appleton, 1868.

- The Satires: Absalom and Achitophel / The Medal / Mac Flecknoe (edited by John Churton Collins). London & New York: Macmillan, 1905.[13]

- The Poems (edited by James Kinsley). (4 volumes), Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1958.

Plays[]

- The Rival Ladies. London: W.W. for Henry Herringman, 1664.

- The Indian Emperour; or, The conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. London: J.M. for H. Herringman, 1667

- second edition (with "A Defence of An Essay of Dramatique Poesie" in some copies). London: Henry Herringman, 1668.

- Secret-Love; or, The maiden-queen. London: Henry Herringman, 1668.

- Sr Martin Mar-All; or The feigned innocence. London: Henry Herringman, 1668.

- The Wild Gallant. London: Tho. Newcomb for H. Herringman, 1669.

- Tyrannick Love; or, The royal martyr. London: Henry Herringman, 1670.

- The Tempest; or, The enchanted island (by Dryden and William Davenant). London: Henry Herringman, 1670.

- An Evening's Love; or, The mock astrologer. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1671.

- The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards: In two parts. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1672.

- Marriage A-la-Mode. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1673.

- The Assignation; or, Love in a nunnery. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1673.

- Amboyna. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1673.

- Aureng-Zebe. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1676.

- All for Love: or, The world well lost. London: Tho. Newcomb for Henry Herringman, 1678.

- Oedipus (by Dryden & Nathaniel Lee). London: R. Bentley & M. Magnes, 1679.

- Troilus and Cressida; or, Truth found too late. London: Jacob Tonson & Abel Swall, 1679.

- The Kind Keeper; or, Mr. Limberham. London: R. Bentley & M. Magnes, 1680.

- The Duke of Guise (by Dryden and Lee). London: T.H. for R. Bentley & J. Tonson, 1683.

- The Spanish Fryar; or, The double discovery. London: Richard Tonson & Jacob Tonson, 1681.

- Cleomenes, The Spartan Heroe. London: Jacob Tonson, 1692.

- Albion and Albanius (by Dryden, with music by Lewis Grabu). London: Jacob Tonson, 1685.

- Don Sebastian, King of Portugal. London: Jo. Hindmarsh, 1690.

- Amphitryon; or, The two Socia's (with music by Henry Purcell). London: J. Tonson & M. Tonson, 1690.

- King Arthur; or, The British worthy (with music by Purcell). London: Jacob Tonson, 1691.

- Love Triumphant; or, Nature will prevail. London: Jacob Tonson, 1694.

- The Dramatick Works. London: Jacob Tonson, 1717. Volume III, Volume V, Volume VI

- The Dramatic Works (edited by Montague Summers). (6 volumes), London: Nonesuch Press, 1931.

Non-fiction[]

- To My Lord Chancellor: Presented on New-years-day. London: Henry Herringman, 1662.

- Of Dramatick Poesie: An essay. London: Henry Herringman, 1668 [1667].

- ([edited by Thomas Arnold). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1896.

- Notes and Observations on the Empress of Morocco (by Dryden, John Crowne, and Thomas Shadwell). London: 1674.

- The State of Innocence and Fall of Man. London: T.N. for Henry Herringman, 1677.

- His Majesties Declaration Defended. London: T. Davies, 1681.

- The Vindication [of the Duke of Guise;: or, The parallel of the French Holy-League, and the English League and Covenant. London: Jacob Tonson, 1683.

- A Defence of the Papers Written by the Late King of Blessed Memory and Duchess of York. London: H. Hills, 1686.

- An Essay of Dramatic Poesy (edited by Thomas Arnold). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1889.

- Essays (edited by C.D. Yonge). London: Macmillan, 1895.

- Essays (edited by W.P. Ker). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1900. Volume I

Collected editions[]

- The Works (edited by Walter Scott). (18 volumes), London: William Miller, 1808 Volume I, Volume II, Volume III, Volume IV, Volume V, Volume VI, Volume VII, Volume VIII,

Volume IX, Volume X, Volume XI, Volume XII, Volume XIII, Volume XIV, Volume XV, Volume XVI, Volume XVII, Volume XVIII.

- (revised by George Saintsbury). Edinburgh: William Paterson, 1882-1893.

- The Works [The California Dryden] ( edited by Edward Niles Hooker, H.T. Swedenberg, and others). (20 volumes), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1955-

- John Dryden: Of Dramatic Poesy, and other critical essays (2 volumes, edited by George Watson). (2 volumes), London: J.M. Dent / New York: E.P. Dutton, 1962.

Translated[]

- Ovid's Epistles: Translated by several hands (includes a preface, and translations of three epistles, by Dryden). London: Jacob Tonson, 1680.

- Louis Maimbourg, The History of the League (translated by Dryden). London: M. Flesher for Jacob Tonson, 1684.

- Dominique Bouhours, The Life of St. Francis Xavier, of the Society of Jesus (translated by Dryden). London: Jacob Tonson, 1688.

- The Satires of Decimus Junius Juvenalis: Translated into English verse. By Mr. Dryden, and Several other eminent hands: Together with the satires of Aulus Persius Flaccus made English by Mr. Dryden ... to which is prefix'd a discourse concerning the original and progress of satire. London: Jacob Tonson, 1693 [1692].

- The Works of Virgil: Containing his Pastorals, Georgics, and Æneis (translated by Dryden. London: Jacob Tonson, 1697.