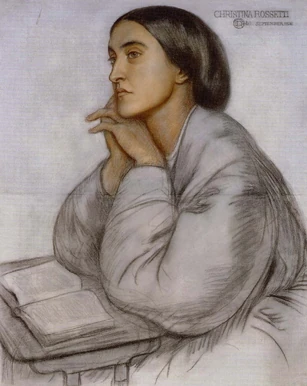

Christina Rossetti (1830-1894). Portrait by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), 1866. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Christina Georgina Rossetti (5 December 1830 - 29 December 1894) was an English poet who wrote a variety of romantic, devotional, and children's poems.

Life[]

Overview[]

Rossetti, the sister of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was born in London, where she lived all her life. She began to write poetry in early girlhood, some of her earliest verse appearing in 1850 in the Germ, the magazine of the Pre-Raphaelites, of which her brother was a founder. Her subsequent publications were Goblin Market, and other poems (1862), The Prince's Progress (1866), A Pageant, and other poems (1881), and Verses (1893). New Poems (1896) appeared after her death. Sing-Song was a book of verses for children. She led a very retired life, passed largely in attending on her mother, who lived until 1886, and in religious duties. She twice rejected proposals of marriage. Her poetry is characterized by imaginative power, exquisite expression, and simplicity and depth of thought. She rarely imitated any forerunner, and drew her inspiration from her own experiences of thought and feeling. Many of her poems are definitely religious in form; more are deeply imbued with religious feeling and motive. In addition to her poems she wrote Commonplace, and other stories, and The Face of the Deep, a striking and suggestive commentary on the Apocalypse.[1]

Educated privately, Rossetti suffered ill-health in her youth, but was already writing poetry in her teens. She produced her first published verse under the pseudonym Ellen Alleyne. Christina rejected the social world of her brother's "Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood", preferring "my shady crevice – which crevice enjoys the unique advantage of being to my certain knowledge the place assigned me." Her engagement to a painter, James Collinson, was broken off because of religious differences (she was High Church Anglican). She also rejected a somewhat less than reputable proposition from John Ruskin. ("Here's friendship for you if you like; but love, --/No, thank you, John.") She is best known for her long poem "Goblin Market", her love poem "Remember", and her words to the Christmas carol "In the Bleak Midwinter".

Youth[]

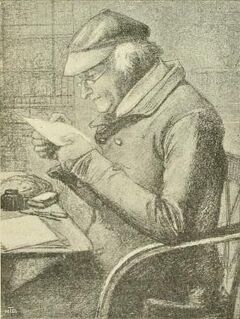

Gabriele Rossetti. Drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), 1853. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Rossetti was the youngest of the 4 children of Gabriele Rossetti,[2] a poet and a refugee from Naples, and Frances (Polidori), the sister of Lord Byron's friend and physician, John William Polidori.[3] She was born at 38 Charlotte Street, Portland Place, London, on 5 December 1830.[2] She had 2 brothers and a sister: Gabriel Dante (who would become an influential artist and poet), William Michael, and Maria Francesca (who would also both become writers). Christina was a lively child. She dictated her first story to her mother before she had learned to write.[3]

Rossetti was educated at home by her mother who supplemented their learning with religious works, classics, fairytales and novels. Rossetti delighted in the work of Keats, Scott, Ann Radcliffe and Monk Lewis.[4] The influence of the work of Dante Alighieri and other Italian writers filled the home and would have a deep impact on Rossetti's later writing.[4]

The family homes at 38 and later 50 Charlotte Street were within easy reach of Madam Tussauds, London Zoo and the newly opened Regent's Park (still wooded), which she visited regularly; In contrast to her parents, Rossetti was very much a London child.[4] She enjoyed the advantages and disadvantages of the strange society of Italian exiles and English eccentrics which her father gathered about him, and she shared the studies of her gifted elder brother and sister.[2]

In the 1840's, her family faced severe financial difficulties due to the deterioration of her father's physical and mental health. In 1843, he was diagnosed with persistent bronchitis, possibly tuberculosis, and faced losing his sight. He gave up his teaching post at King's College and though he lived another 11 years, he suffered from depression and was never physically well again. Rossetti's mother began teaching in order to keep the family out of poverty and Maria became a live-in governess, a prospect that Christina Rossetti dreaded. At this time her brother William was working for the Excise Office and Gabriel was at art school, leading Christina's life at home to increasingly isolated.<ref name="Packer20">Packer, Lona Mosk (1963) Christina Rossetti University of California Press, 20.</ref>

In her girlhood she had a grave, religious beauty of feature, and sat as a model not only to her brother Gabriel, but to Holman Hunt, to Madox Brown and to Millais. As early as 1847 her grandfather, Gaetano Polidori, printed privately a volume of her Verses, in which the richness of her vision was already faintly prefigured. In 1850 she contributed to The Germ 7 pieces, including some of the finest of her lyrics.[2]

Career[]

Drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In 1853-1854 Rossetti for nearly a year helped her mother to keep a day-school at Frome-Selwood, in Somerset. Early in 1854 the Rossettis returned to London, and the father died. In poverty, in ill-health, in extreme quietness, she was now performing her life-work. She was twice sought in marriage, but each time, from religious scruples (she was a strong high church Anglican), she refused her suitor; on the former of these occasions she sorrowed greatly, and her suffering is reflected in much of her early song.[2]

In 1861 she saw foreign countries for the 1st time, paying a 6 weeks' visit to Normandy and Paris. In 1862 she published what was practically her earliest book, Goblin Market, and took her place at once among the poets of her age. The Prince's Progress followed in 1866.[2]

In 1867 she, with her family, moved to 56 Euston Square, which became their home for many years. Christina's prose work Commonplace appeared in 1870. In April 1871 her whole life was changed by a terrible affliction, known as “Graves's disease"; for 2 years her life was in constant danger.[2] She had already composed her book of children's poems, entitled Sing-Song, which appeared in 1872.[5]

After a long convalescence, she published in 1874 2 works of minor importance, Annns Domini and Speaking Likenesses. The former is the earliest of a series of theological works in prose, of which the 2nd was Seek and Find in 1879. In 1881 she published a 3rd collection of poems, A Pageant, in which there was evidence of slackening lyrical power.[5]

She now gave herself almost entirely to religious disquisition. The most interesting and personal of her prose publications (but it contained verse also) was Time Flies (1885) – a sort of symbolic diary or collection of brief homilies.[5]

In 1890 the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge published a volume of her religious verse. She collected her poetical writings in 1891. In 1892 she was led to publish a very bulky commentary on the Apocalypse, entitled The Face of the Deep. After this she wrote little.[5]

Last years[]

Her last years were spent in retirement at 30 Torrington Square, Bloomsbury, which was her home from 1876 to her death. In 1892 her health broke down finally,[5] in 1893, she developed breast cancer and though the tumou was removed, she suffered a recurrence in September 1894. She died on 29 December 1894 and was buried in Highgate Cemetery.[6]

Writing[]

When I am dead, my dearest

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

Her New Poems were published posthumously in 1896.[5]

In spite of her manifest limitations of sympathy and experience, Christina Rossetti takes rank among the foremost poets of her time. In the purity and solidity of her finest lyrics, the glow and music in which she robes her moods of melancholy reverie, her extraordinary mixture of austerity with sweetness and of sanctity of tone with sensuousness of color, Christina Rossetti, in her best pieces, may challenge comparison with the most admirable of our poets.[5]

In Goblin Market is still to be found a majority of her finest writings.[2] The title poem is 1 of Rossetti's best known works. Although it is ostensibly about 2 sisters' misadventures with goblins, critics have interpreted the piece in a variety of ways: seeing it as an allegory about temptation and salvation; a commentary on Victorian gender roles and female agency; and a work about erotic desire and social redemption. Rossetti was a volunteer worker from 1859 to 1870 at the St. Mary Magdalene "house of charity" in Highgate, a refuge for former prostitutes and it is suggested Goblin Market may have been inspired by the "fallen women" she came to know. [8] There are parallels with Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner given both poems' religious themes of temptation, sin and redemption by vicarious suffering.[9]

She was ambivalent about women's suffrage, but many scholars have identified feminist themes in her poetry[10] She was opposed to slavery (in the American South), cruelty to animals (in the prevalent practice of animal experimentation), and the exploitation of girls in under-age prostitution. [11]

The union of fixed religious faith with a hold upon physical beauty and the richer parts of nature has been pointed to as the most original feature of her poetry. Hers was a cloistered spirit, timid, nun-like, bowed down by suffering and humility; her character was so retiring as to be almost invisible. All that we really need to know about her, save that she was a great saint, was that she was a great poet.[5]

Critical introduction[]

by Percy Lubbock

The peculiar gift of Christina Rossetti is among the rarest in poetry, if not of the greatest: it is the gift of song. She had a fountain of music within her which never ceased altogether in her life, strangely as her life seemed to narrow itself and her shy difficult spirit to shrink from experience. She was a cloistered soul that mistrusted the attraction of the world, turning away from it, not indeed in fear, but with a conviction of its vanity. The world had all the charm for her that it has for an exquisite and sensuous nature; yet her rejection of it, with whatever sacrifice of herself, was sober and deliberate, for she did not know the great disruptive forces of illumination and conversion. She was inexperienced even in the fevour of her saintliness. Her fine powers of mind and imagination were kept in a narrow groove by a puritan rule which she adopted from the very first and held to the end. She would not move outside it, surrounded though she was with some of the fullest and most striking opportunities, æsthetic and intellectual, of her generation. It is a curiously grey and insular story for a poetess of her origin and endowment, and the strangest part of it all is that her vivid lyrical impulse never entirely left her or lost its freedom.

The world of her own, the world she elected to live in, had this opening towards the outer air, and she made the most of it. Having protected herself against life, once for all, by a code of duty unnaturally arid, in her poetry she drew close to a kind of beauty that was all earthly warmth and fragrance. She who moved in fact through a maze of anxious scruples could here pass out, with a power of undimmed enjoyment, into an almost Hellenic sunshine. There is to be found in her earlier poems, and not only in these, a franker and simpler delight in the budding and flowering and fruiting of nature, in the turn of the quick tractable English seasons, in the happy grace of birds and furry creatures, than has often been seen in a literature in which, for the most part, the natural world is made the very groundwork of philosophy.

Christina Rossetti had no need of a philosophy, for she never doubted the meaning of life, sorely as she might doubt herself. When she could escape from this perplexity, therefore, she was as free as a swallow, and her native humanity, clear and sane and direct, enjoyed the earth and its increase without a question. The dawn and flush of spring, the rapture of young love, the lark-song of a summer cornfield—she knew and uttered such moments with a music that has their very own sense of wonder and newness and liberation. She does not study or describe, but her verse is continually full of country weather, airs blowing and sunlight falling—images caught and reflected in a memory as lucid, as keen and thoughtless, as a child’s.

The beautiful originality of her poems in this mood is of a kind that makes her the truest “Pre-Raphaelite” of all the famous group. If the word was meant to imply a way of looking at things with new eyes and an ingenuous mind, it suited her long after her brother and the rest had diverged upon their different lines. They were soon corrupted by knowledge and reflection, and passed on to maturity. Christina never matched their achievement, but neither could they show anything like the spring-charm, the wild-fruit savour that her work so often had even in later years.

Her fine felicity in romance sprang straight from an imagination which in a sense was always as bare and clear as the room where she sits in her brother’s painting of the Annunciation. She could let her fancy riot, as in Goblin Market, with wayward profusion; but its opulence is that of a dream, with no attachment to life and ready to vanish in a moment. It was an imagination acutely sensitive to the colour and shape and touch and taste of things—of queer and grotesque things as much as any other. But the mere world could not lay hold on it, and for this very reason it stands out with a singular shining freshness. If ever in her work she ventured, as she seldom did, into actual life, it was evidently because she was tempted by the example of Mrs. Browning; and she was then betrayed into a kind of sentimentality very unlike Mrs. Browning’s passionate intellectual honesty. In the world of dreams her brilliance, audacity, even humour, are always alive and true.

Her lyrical youth survived in her, then, carrying with it youth’s obstinate anxieties, but never absorbed, either to its enrichment or its extinction, in a wider range of interests. She clung to the faith she had found in her earliest years and allowed it, for hard reasons that seemed good to her, to cut her off from a fuller emotional life. It was not so much any mystical ardour that saved her from embitterment as the mere kindly naturalness of the impulses she crossed. The flame of her spirit was bright, by its own human virtue, through all her long and grievous self-vexation; and there are poems of hers, those that are now perhaps most often returned to, in which it glows with a profoundly attaching and appealing beauty. It might be a slender handful of experience that fed the fire; but there could be nothing loftier than the sincerity with which the single-minded votaress of an ideal passion refused to misunderstand or to misprize the memory she guarded. The poetry she dedicated to it has the charm of a perfect loyalty to the sweetness of earthly love. If, for trust in its power, she lacked a certain generosity of soul, she would not for that deny it, or attempt to give it any name but its own. No songs or elegies of love show a simpler and straighter sense of its magic than do hers, and in few is it expressed with a melody more fervent and eager. Their pathos is very great, for even in disappointment and disillusion they retain the sensitive candour of youth, with all its power of suffering and all its instinct for happiness.

But the burden of her creed lay heavily on her — so heavily, so little to her encouragement or even her peace of mind, that it seems alien to her, as though it must have been imposed, as perhaps it was to some extent, by a stronger will from without. Her elder sister was apparently altogether satisfied and reassured by the support of a narrow faith; but Christina was not satisfied, she was only determined to be; and she was far indeed, even to the end, from ever being reassured. She was haunted and dismayed by the thought of her unworthiness, not inspired by it; and this discord in her nature affected her genius unfortunately, as was natural; the wonder is that it did not ruin and stifle it. A monotony of mood asserted itself more and more in her work. She held fast to the idea that the only road to harmony is through renunciation; but the passion she poured into the act of self-sacrifice, strong as it was, had not the substance, had rather, perhaps, a too pure and artless simplicity, to create a positive life for her in the ideal. She missed the freedom of adventure and exultation that is discovered there by the true mystic. The poetry of Christina Rossetti touches this height at moments, but generally it is caught by the way on the thorny sense of her own ingratitude and faithlessness, and preoccupied to excess with the stern contrast between the enchantments of the world and the promises of eternity.

None the less her “devotional” poetry, though wanting vigor of thought, is always distinguished, and of rare splendor at its best. The movement of her genius had a peculiar dignity; and though she wrote much that has no great value, much that is merely tentative and but half-expressed, she wrote almost nothing which does not show the controlled nerve of an admirable style. Her command of rhythm and metre, by no means faultless, had a very remarkable scope. She adopted or invented a great variety of measures, and used them with an ease which falls short of real mastery only through lacking the last edge of care; her spontaneity is equally unforced, whether it flings out its own irregular but living shape or whether it fills a traditional form, and some of her effects of repeated rhymes and refrains have the happiest originality. And mastery, with no qualification whatever, is displayed in the robustness and purity of her diction. She learned it from the Bible, of course, but there was something in it which she perhaps learned also from the only other book she studied much, the Divine Comedy. If she could marshal a pomp of words with prophetic fervour, she could give to homely turns and phrases a stateliness and gravity which at times is not far from the art of Dante. Such sympathy for words, such perception of their value and ring, is for whatever reason rarely a feminine gift; and in all this Christina Rossetti had a wider reach and a surer taste than any woman who has written our language—she, the English poetess to whom it was not native.

But her place among all great poets is not less certain. In spite of her limitations and her thwarted development, she had the true heart of song; and by virtue of it she has her own supremacy. Song which seems to draw its life from the dew and breeze of summer, warm ripeness that is yet freshness, transparent sunshine that has still the suggestion of clean showers—such is the song of Christina Rossetti, and her slender achievement is in its way unique. Life should have fostered a genius and nature like hers. Her instinct was entirely lyrical, and even when she wished to write allegories and moralities, The Prince’s Progress or the Convent Threshold, pure irresponsible music would break out uncontrollably in her argument. It must seem a calamity of poetry that she should have missed a fuller growth and that so much of her work should have been overhung with sterile shadows. Away from them she uttered some of the most singing melodies, blithe and sad, to be found in English verse.[12]

Critical reputation[]

In the early 20th century Rossetti's popularity faded in the wake of Modernism. In the 1970's scholars began to rediscover and critique her work again, and it regained admittance to the Victorian literary canon.

Recognition[]

James Taylor - In The Bleak Midwinter

11 of her poems ("Bride Song," "A Birthday," "Song," "Twice," "Uphill," "Passing Away," "Marvel of Marvels," "Is it Well with the Child?", "Remember," "Aloof," and "Rest") were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[13]

Rossetti is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on April 27.

Her Christmas poem "In the Bleak Midwinter" became widely known after her death when set as a much loved Christmas carol, first by Gustav Holst, and then by Harold Darke.[14] Her poem "Love Came Down at Christmas" (1885) has also been widely arranged as a carol.[15]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Verses. London: privately published, printed by G. Polidori, 1847.

- Goblin Market, and other poems. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan, 1862; Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1866.

- author's revised edition, 1876.[16]

- New York: Dover, 1994; Cambridge, UK Salt Publishing, 2009.

- The Prince's Progress, and other poems. London: Macmillan, 1866.

- Poems. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1866

- Author's edition (revised and enlarged). Boston: Little, Brown, 1876.

- Goblin Market, The Prince's Progress, and other poems . London: Macmillan, 1879.

- A Pageant, and other poems. London: Macmillan, 1881.

- Poems (new and enlarged edition). London: Macmillan, 1890.

- Verses (edited by Hugh De Bock Porter & Mary E Porter). London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge / New York: E. & J.B. Young, 1893.

- Posthumous

- New Poems: Hitherto unpublished or uncollected (edited by William Michael Rossetti). London & New York: Macmillan, 1896.

- The Rossetti Birthday Book (edited by Olivia Rossetti Agresti). London: Macmillan, 1896.

- Poetical Works (edited by William Michael Rossetti). London & New York: Macmillan, 1904.

- Poems (introduction by Alice Meynell; illustrated by Florence Harrison). London: Blackie, 1906.

- Selected Poems (edited by Alexander Smellie). London: Andrew Melrose, 1907.

- Selected Poems (edited by Charles Bell Burke). New York: Macmillan, 1913.

- Poems Chosen (edited by Walter de la Mare). Newtown, Montgomeryshire, UK: Gregynog Press, 1930.

- Selected Poems (edited by Marya Zaturenska). London & New York: Macmillan, 1970.

- A Choice of Christina Rossetti's Verse (edited by Elizabeth Jennings). London: Faber & Faber, 1970.

- Complete Poems (variorum edition; edited by Rebecca W Crump). (3 volumes), Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. Volume I, 1979; Volume II, 1986; Volume III, 1990.

- abridged (1 volume), London & New York: Penguin, 2001.

- Selected Poems (edited by C.H. Sisson). Manchester, UK: Carcanet, 1984.

- Selected Poems (edited by Katherine McGowran). Ware, Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 2001.

- The Poetry of Christina Rossetti (edited by Emma Topping). Guildford, UK: Saland, 2011.

Short fiction[]

- Commonplace, and other short stories. London: F.S. Ellis, 1870; Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1870.

Non-fiction[]

- Annus Domini: A prayer for each day of the year, founded on a text of Holy Scripture. London & Oxford, UK: James Parker, 1874.

- Seek and Find: A double series of short studies of the Benedicite. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge / New York: Pott, Young, 1879.

- Called to Be Saints: The minor festivals devotionally studied. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge / New York: E. & J.B. Young, 1881.

- Letter and Spirit: Notes on the Commandments. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge / New York: E. & J.B. Young, 1883.

- "Dante: An English classic" in Churchman's Shilling Magazine and Family Treasury 2 (1867): 200-205.[16]

- "Dante: The poet illustrated out of the poem." The Century (February 1884): 566-73.[16]

- The Face of the Deep: A devotional commentary on the Apocalypse.. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge / New York: E. & J.B. Young, 1892.

Juvenile[]

- Sing-Song: A nursery rhyme book. London: George Routledge, 1872

- enlarged edition. London & New York: Macmillan, 1893.

- Sing-Song: A nursery rhyme book, and other poems for children (illustrated by Marguerite Davis). New York: Macmillan, 1922.

- Verses from Sing-Song (edited by Marion R. Kohs). New York: Pied Piper, 1945.

- Sing-Song: A nursery rhyme book (illustrated by Arthur Hughes). New York: Dover, 1968.

- Speaking Likenesses. London & New York: Macmillan, 1874.

- Maude: A story for girls. London: J. Bowden, 1897.

- published in U.S. as Maude: Prose and verse. Chicago: H.S. Stone, 1897.

- Poems for Children (edited by Melvin Hix). New York & Boston: Educational Publishing, 1907.

- What is Pink? (illustrated by Jose Aruego). New York: Macmillan, 1971.

- Fly Away, Fly Away, Over the Sea, and other poems for children (illustrated by Bernadette Watts). New York: North-South, 1991.

- Color: A poem (illustrated by Mary Teichman). New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Collected editions[]

- Selected Prose (edited by David A Kent & P.G. Stanwood). New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

- Works (edited by Martin Comer). Ware, Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1995.

- Prose Works. Bristol, UK: Thoemmes Press / Tokyo: Edition Synapse, 2003.

- Poems and Prose (edited by Simon Humphries). Oxford, UK, & New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Letters and journals[]

- Time Flies: A reading diary. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1885; Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1886.

- Family Letters; with some supplementary letters and appendices (edited by William Michael Rossetti). London: Brown, Langham, 1908

- New York: Haskell House, 1968; Folcroft, PA: Folcroft Library Editions, 1973.

- The Rossetti-Macmillan Letters: Some 133 unpublished letters written to Alexander Macmillan, F.S. Ellis, and others, by Dante Gabriel, Christina, and William Michael Rossetti, 1861-1889 (edited by Frederick Startridge Ellis). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1963.

- Letters (edited by Anthony H. Harrison). Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2004.

- Volume I: 1843-1873, 1997

- Volume II: 1874-1881, 1999

- Volume III: 1882-1886, 2000

- Volume IV: 1887-1894, 2004.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[17]

Christina Rossetti "The Bourne" Poem animation

Christina rossetti "Twice" Poem animation

Who Has Seen The Wind? a poem by Christina Rossetti

Poems by Rossetti[]

See also[]

References[]

- Clifford, David & Roussillon, Laurence. Outsiders Looking In: The Rossettis Then and Now. London: Anthem, 2004.

Gosse, Edmund (1911). "Rossetti, Christina Georgina". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 746-747.. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 23, 2018.

- Jones, Kathleen. Learning Not to be First: A Biography of Christina Rossetti. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Marsh, Jan. Introduction. Poems and Prose. By Christina Rossetti. London: Everyman, 1994. xvii – xxxiii.

- Marsh, Jan. Christina Rossetti: A Writer's Life. New York: Viking, 1994.

Fonds[]

- A Guide to the Christina Georgina Rossetti Collection: Archive at the Bryn Mawr College Library

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "Rossetti, Christina Georgina," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: Dent / New York: Dutton, 1910, 321-322. Wikisource, Web, Feb. 23, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Gosse, 746.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Author Profile: Christina Rossetti," Literary Worlds, BYU.edu, Web, May 19, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Packer, Lona Mosk (1963) Christina Rossetti University of California Press pp13-17

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Gosse, 747.

- ↑ Antony H. Harrison (2004) The Letters of Christina Rossetti Volume 4, 1887-1894 University of Virginia Press ISBN 0-8139-2295-X

- ↑ Christina Rossetti, "When I am dead, my dearest", Poetry Foundation, Web, July 16, 2011.

- ↑ Packer, Lona Mosk (1963) Christina Rossetti University of California Press p155

- ↑ Hassett, Constance W. (2005) Christina Rossetti: the patience of style University of Virginia Press p15

- ↑ Pieter Liebregts and Wim Tigges (Eds.) (1996) Beauty and the Beast: Christina Rossetti. Rodopi Press. p43

- ↑ Fairchild, Hoxie Neale (1939) Religious trends in English poetry, Volume 4 Columbia university press.

- ↑ from Percy Lubbock, "Critical Introduction: Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830–1894)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 25, 2016.

- ↑ Alphabetical list of authors: Montgomerie, Alexander to Shakespeare, William, Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch). Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 19, 2012.

- ↑ BBC article Bleak Midwinter named best carol Thursday, 27 November 2008

- ↑ Hymns and Carols of Christmas

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Anthony H. Harrison, "Bibliography for Christina Rossetti in Context," The Victorian Web, May 19, 2011.

- ↑ Search results = au:Christina Rossetti, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Nov. 3, 2013.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Winter: My secret"

- Christina Rossetti 1830-1884 at the Poetry Foundation

- Rossetti in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900: "Bride Song," "A Birthday," "Song," "Twice," "Uphill," "Passing Away," "Marvel of Marvels," "Is it Well with the Child?", "Remember," "Aloof," and "Rest").

- Rossetti in the Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse: "Hymn, after Gabriel Rossetti," "After Communion."

- 11 poems by Rossetti: "A Dirge," "Good Friday," "Love came down at Christmas," "Old and New Year Ditties (3 poems)," "Winter Rain," "By the Sea," "An October Garden," "In the Bleak Mid-winter," "May"

- The Best Christina Rossetti Poems Everyone Should Read at Interesting Literature (10 poems)

- Rossetti in The English Poets: An anthology: "Noble Sisters," "Dream Land," "Bride-Song" (from The Prince's Progress), Song: "When I am dead, my dearest", "A Birthday," "At Home," "Up-hill," "Shut Out," "Echo," "A Christmas Carol," "Passing Away"

- Rossetti in A Book of Women's Verse: Song: "When I am dead, my dearest", Song: "The irresponsive silence of the land:, "Echo," "A Soul," "Good Friday," "Twice," "Rest," "Up-hill," "Remember," "Bride-Song," "A Birthday," "Amor Mundi, "In Progess," "What Would I Give?"

- Christina Rossetti in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895 (15 poems)

- Selected Poetry of Christina Rossetti (1830-1894) (16 poems) at Representative Poetry Online

- Christina Rossetti profile & 18 poems, including "Goblin Market", at the Academy of American Poets

- Christina Georgina Rossetti at PoemHunter (308 poems)

- Christina Georgina Rossetti at Poetry Nook (1,117 poems)

- Audio

- Audio: Robert Pinsky reads "Song" by Christina Rossetti (via poemsoutloud.net)

- Christina Rossetti at YouTube

- Books

- Works by Christina Rossetti at Project Gutenberg

- Christina Rossetti at Amazon.com

- About

- Christina Rossetti in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Christina Rossetti at NNDB

- Rossetti, Christina Georgina in the Dictionary of National Biography

- Christina Georgina Rossetti in The Germ

- Christina Rossetti at the Victorian Web

- Christina Rossetti in Context by Anthony H. Harrison

- Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, London

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at Rossetti, Christina Georgina

|