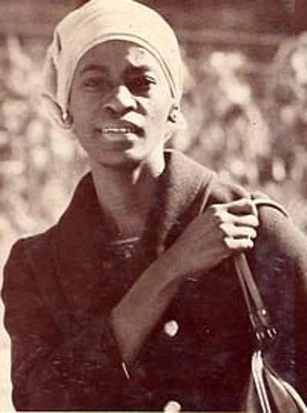

Carolyn Rodgers (1940-2010). Courtesy Essence.

Carolyn Marie Rodgers (December 14, 1940[1] - April 2, 2010) was a Chicago-based African-American poet,[2] and a founder of 1 of America’s oldest and largest black presses, Third World Press.

Life[]

Youth and education[]

Born and raised in Chicago, Rodgers initially attended college at the University of Illinois in 1960, but transferred to Chicago’s Roosevelt University in 1961 where she earned her B.A. degree in 1965. She later earned an M.A. in English from the University of Chicago in 1980.

Career[]

Rodgers got her start in the literary circuit as a young woman studying under Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks in the South Side of Chicago.

In 1967 Rodgers founded Third World Press with Haki R. Machumbuti, Johari Amini, and Rochelle Rich. Years later she founded Eden Press with a grant from the Illinois Arts Council.[3]

Rodgers began writing her own works, which grappled with black identity and culture in the late 1960s. Rodgers was a leading voice of the Black Arts Movement and authored 9 books including How I got Ovah. She was also an essayist and critic, and her work has been described as delivered in a language rooted in a black female perspective[4] that wove strands of feminism, black power, spirituality, and writerly self-consciousness into a sometimes raging, sometimes ruminative search for identity.

She became distinctive as a new black woman poet in the 1960s with the publication of her first 2 books, Paper Soul and Songs of the Blackbird.

Rodgers is best known for her writing contributions to the Black Arts Movement (BAM). Rodgers became involved in writing during the BAM while attending Writers Workshops by the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) and Gwendolyn Brooks.

Writing[]

Poetry and poetics[]

Early poetry[]

Rodgers' poetry is recognizable for its themes which included identity, religion, and revolution, and her own use of free verse street slang and concern with feminine issues. In her early days, black revolutionary themes and cuss words wove through some poems.

Rodgers used slang and heartfelt language to write about love, lust, body image, family, religion, and the grace of human kindness. In her earliest writings such as Paper Soul (1968) and Songs of a Blackbird (1969), Rodgers revolutionary ideas about women’s roles conflicted with the more traditional ideas of the African American culture. She was criticized for her use of profanity which male leaders of BAM found inappropriate for a woman.

Haki R. Madhubuti, chair, publisher and fellow founder of Third World Press, told the Chicago Sun Times that "she would take no quarter from insults, or downgrading her writing as a woman.... Her writing could stand by itself."[5]

So while Rodgers' Songs of the Blackbird includes themes about survival, mother-daughter conflicts, and street life it also criticizes those who dishonor her use of profanity. In her poem “The Last M.F.” she fights back:

they say,

that I should not use the word

mothafucka anymo

in my poetry or in any speech I give.

they say,

that I must and can only say it to myself

as the new Black Womanhood suggests

a softer self

In “The Last M.F.” Rodgers says she will stop using profanity but continues using the “menacing word” at least eleven times throughout the poem, blatantly making jabbs at men and their ideas of how a woman should speak and behave. Here too, Rodgers mocks the new Black Womanhood which she believes, paradoxically, promotes women to be silent.

Later poetry[]

Other volumes of work such as The Heart as Ever Green (1978) and How I Got Ovah (1975) also reflect on feminine issues such as female identity, women’s roles in society, and the relationships between mothers and daughters. However, How I Got Ovah exhibits a more crafted tendency than previous books, along with being more autobiographical and transformative. By now Rodgers was distilling her language and militant persona into poetry that was deeply concerned with religion, God, and the quest for inner beauty.

If this cannot be characterized as transformative, nonetheless her work seems to have shifted from a collective black perspective in her early work to an individual perspective[2] in her later writings. Consequently, by the time she published The Heart as Ever Green in 1978, Rodgers was incorporating earlier themes of feminism and human dignity in her poems, along with newer or more pronounced themes of love and Christianity.

Some readers and cultural observers don't recognize a break or rupture from Rodgers' past in her later work. For them, Rodgers' spiritual progress in her poetry still brings a radical infusion. Even in her later poetry, we can still break open into a vision uniquely situated in a poetics that remains strident, militant and experimental.

Fiction and literary criticism[]

Rodgers' earned an appreciative and crucial audience through her fiction and literary criticism. Marsha C. Vick points out some of the reasons why:

- The same insight and searching analysis that distinguish her poetry are integral to Rodgers's short fiction and her literary criticism. She portrays in her short fiction the ordinary and overlooked people in everyday African American life and emphasizes the theme of survival. Many consider her critical essay “Black Poetry—Where It's At” (1969) to be the best essay on the work of the “new black poets.” In it, she aesthetically evaluates contemporary African American poetry and sets up preliminary criteria of appraisal. [6]

According to poet Lorenzo Thomas, Rodgers proposed new prosodic categories specific to black poetry. Thomas points out that this kind of essay (or manifesto) outlining a vision statement to spur militant and creative inquiry (but most particularly “Black Poetry—Where It's At”) was widely disseminated and discussed among poets of that time.[7]

Recognition[]

Following the publication and national success of Paper Soul (1968), Rodgers was awarded the inaugural Conrad Kent Rivers Memorial Fund Award. Rodgers also won the Poet Laureate Award from the Society of Midland Authors in 1970. She alson received an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, following the 1969 publication of Songs of the Blackbird.

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Paper Soul. Chicago: Third World Press, 1968.

- Songs of a Black Bird. Chicago: Third World Press, 1969.

- 2 Love Raps. Chicago: Third World Press, 1969.

- For H.W. Fuller. Chicago: Third World Press, 1969.

- Now Ain't That Love? Detroit, MI: Broadside Press, 1970.

- A Long Rap: Commonly known as a poetic essay. Detroit, MI: Broadside Press, 1971.

- How I Got Ovah: New and selected poems. Garden City, NY: Anchor, 1975.

- The Heart as Ever Green: Poems. Garden City, NY: Anchor / Doubleday, 1978.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[8]

See also[]

Poem From Space to Time by Carolyn M. Rodgers

5 Poems by Carolyn Rodgers

References[]

- Davis, Jean. “Carolyn M. Rodgers,” in Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 41, Afro-American Poets since 1955, eds. Trudier Harris and Thadious M. Davis, 1985, 287–295

- Nelson, Carrie. Anthology of Modern American Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 1095-1097.

- Parker-Smith, Bettye J., “Running Wild in Her Soul: The poetry of Carolyn Rodgers,” in Black Women Writers, 1950–1980: A critical evaluation, ed. Mari Evans, 1984, 393–410.

- Thomas, Lorenzo. Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric modernism and twentieth-century American poetry. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 2000.

Notes[]

- ↑ according to Library of Congress Authority Files her birth year was 1940, although their source seems to be the New York Times (see: http://authorities.loc.gov/webvoy.htm)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 BRUCE WEBER, "Carolyn Rodgers, Poet, Is Dead at 69", New York Times, April 19, 2010.

- ↑ Carolyn M. Rodgers 1940-2010, Poetry Foundation. Web, Nov. 9, 2018.

- ↑ Funeral Held For Chicago Poet Founding Black Press

- ↑ CAROLYN M. RODGERS: 'Great poet' born of '60s

- ↑ Marsha C. Vick, Carolyn M. Rodgers, Oxford Book of African American Verse, Oxford University Press, 2002. Answers.com, Web, Nov. 9, 2018.

- ↑ Thomas, Lorenzo. Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry. Tuscaloosa and London: The University of Alabama Press, 2000. p211. Thomas then goes on to point out that: "Her [Rodgers] ideas were based on what Jerry W. Ward, Jr., has called 'culturally anchored SPEECH ACTS and Reader/Hearer Response.'"

- ↑ Search results = au:Carolyn M. Rodgers, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, Jan. 26, 2015.

External links[]

- Poems

- "Some Me of Beauty"

- RIP + Poem: Carolyn Rodgers ("Poem for Some Black Women")

- Carolyn M. Rodgers 1941-2010 at the Poetry Foundation

- Online Poems by Carolyn M. Rodgers.

- Audio / video

- Books

- Carolyn M. Rodgers at Amazon.com

- About

- Carolyn Marie Rodgers at Voices from the Gaps

- Carolyn M. Rodgers in the Oxford Companion to African-American Literature

- Black Arts Movement star Carolyn M. Rodgers dead at 69

- Carolyn M. Rodgers Dead at 69, Chicago poet and writer helped found black press from the Huffington Post

- Carolyn M. Rodgers (1940-2010) at Modern American Poetry

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia. (view article). (view authors). |

|