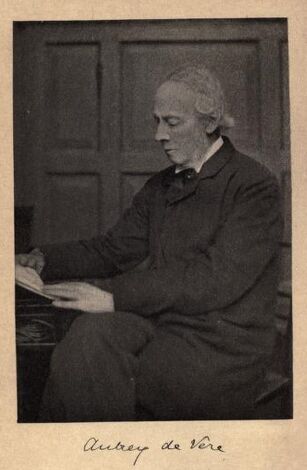

Aubrey Thomas de Vere (1814-1902), from Selections from the Poems of Aubrey de Vere, 1894. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Aubrey Thomas de Vere (10 January 1814 - 20 January 1902) was an Irish poet and literary critic.

Life[]

Overview[]

De Vere, son of Sir Aubrey de Vere (himself a poet), was born in co. Limerick, and educated at Trinity College, Dublin. In early life he became acquainted with Wordsworth, by whom he was greatly influenced. On the religious and ecclesiastical side he passed under the influence of Newman and Manning, and in 1851 was received into the Church of Rome. He was the author of many volumes of poetry, including The Waldenses (1842) and The Search for Proserpine (1843). In 1861 he began a series of poems on Irish subjects, Inisfail, The Infant Bridal, Irish Odes, etc. His interest in Ireland and its people led him to write prose works, including English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds (1848); and to criticism he contributed Essays Chiefly on Poetry (1887). His last work was his Recollections (1897). His poetry is characterised by lofty ethical tone, imaginative power, and grave stateliness of expression.[1]

Family[]

De Vere was born at Curragh Chase, Adare, co. Limerick, Ireland, the 3rd son of a family of 5 sons and 3 daughters of Aubrey Thomas Hunt (afterwards Sir Aubrey de Vere, 2nd baronet), by his wife Mary (died 1856), eldest daughter of Stephen Edward Rice of Mount Trenchard, co. Limerick, and sister of Thomas Spring-Rice, first Lord Mont Eagle. His elder brothers Vere and Stephen de Vere successively inherited their father's baronetcy.[2]

Youth and education[]

Save for a 3 years' visit to England between 1821 and 1824, Aubrey's boyhood was spent at his Irish home, where he was educated privately. While he was a boy a tutor encouraged an enthusiasm for English poetry, especially that of Wordsworth.[2]

In October 1832 he entered Trinity College, Dublin. "Almost all the university course" was uncongenial and he devoted himself to metaphysics. In 1837 he won the "first Downes premium" for theological essay-writing. He left college next year.[2]

To his father's wish that he should take orders in the established church he offered no objection and the idea was present to his mind for many years, but no active step was taken. His time was spent in travel or in literary and philosophical study.[2]

Early travels and friendships[]

In 1838 he visited Oxford and there met Cardinal Newman, who after Wordsworth's death filled the supreme place in De Vere's regard, and Sir Henry Taylor, who became his lifelong friend. Next year he visited Cambridge and Rome. He was introduced at London or Cambridge to the circle which his eldest brother Vere and his cousin, Stephen Spring Rice, had formed at the university; of this company Tennyson was the chief, but it included Monckton Milnes, Spedding, Brookfield, and Whewell.[2]

In 1841 De Vere, whose admiration of Wordsworth's work steadily grew, made the poet's acquaintance in London. In 1843 he stayed at Rydal. He regarded the invitation as "the greatest honour" of his life, and the visit was often repeated. He came to know Miss Fenwick, Wordsworth's neighbour and friend, and he began a warm friendship, also in 1841, with Coleridge's daughter, Sara Coleridge.[2]

In 1843-1844 De Vere travelled in Europe, chiefly in Italy, with Sir Henry Taylor and his wife. In 1845 he was in London, seeing much of Tennyson, and in the same year he made Carlyle's acquaintance at Lord Ashburton's house. Later friends included Robert Browning and R.H. Hutton.[2]

Career[]

From Poetry and Songs of Ireland, 1887. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

De Vere began his career as a poet by publishing in 1842 The Waldenses, and other poems, a volume containing some sonnets and lyrics which now have a place in modern anthologies. The Search after Proserpine, and other poems came out in 1843, the title poem winning Landor's praise.[2]

After visits to Scotland and the Lakes, De Vere returned to Ireland at the beginning of 1846 to find the country in the grip of the famine. He threw himself into the work of the relief committees with unexpected practical energy. In a poem "A Year of Sorrow" he voiced the horrors of the winter 1846-1847. Turning to prose, in which he showed no smaller capacity than in verse, he published in 1848 English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds. There he supported the union and loyalty to the crown, but betrayed intense Irish sympathy, criticised methods of English rule, and deprecated all catholic disabilities. Through all the critical events in Irish history of his time he maintained the same point of view. He always opposed concession to violent agitation, but when, after the Phoenix Park murders in 1882, he wrote a pamphlet on Constitutional and Unconstitutional Political Action,[2] he admitted no weakening in his love of his country.[3]

The death of his father in July 1846 and the experience of the Irish famine deepened De Vere's religious feeling, and from 1848 his sentiment inclined towards the Roman catholic church. Carlyle and other friends warned him in vain against the bondage which he was inviting. But in Novemmber 1851 he set out for Rome in company with Henry Edward Manning, and on 15 November was received into the Roman catholic church on the way in the archbishop's chapel at Avignon.[3]

In 1854 he was appointed by the rector, Newman, to be professor of political and social science in the new Dublin catholic university (cf. Wilfrid Ward, Cardinal Newman, i. 359, 1912). He discharged no duties in connection with the post, but he held it in name until Newman's retirement in 1858. At Pope Pius IX's suggestion he wrote May Carols, hymns to the Virgin and saints (1857; 3rd edit. 1881), with an introduction explaining his conversion.[3]

Thenceforth he lived chiefly in his beautiful Irish home, exchanging visits and corresponding with his friends and publishing much verse and prose. Tennyson had spent 5 weeks with de Vere at Curragh in 1848, and de Vere from 1854 onwards constantly visited Tennyson at Farringford and Aldworth.[3]

Always interested in Irish legend and history, De Vere published in 1862 Inisfail: A lyrical chronicle of Ireland, illustrating the Irish annals of 6 centuries, and after another visit to Rome in 1870 set to work on The Legends of St. Patrick, his most important work of the kind, which appeared in 1872. He made an initial attempt at poetic drama in Alexander the Great (1874), which was followed by St. Thomas of Canterbury in 1876. The 2 dramas were designed to contrast pagan and Christian heroism.[3]

Final years[]

De Vere was a charming conversationalist; his grace of thought and expression was said to shed "a moral sunshine" over the company of hearers, and he told humorous Irish stories delightfully.[3] He was of tall and slender physique, thoughtful and grave in character, of exceeding dignity and grace of manner, and retained his vigorous mental powers to a great age. According to Helen Grace Smith, he was among the most profoundly intellectual poets of his time.[4]

Death of friends saddened his closing years. He published a volume of Recollections in 1897, and the next year he revisited the Lakes and other of his early English haunts. He died unmarried at Curragh Chase on 21 January 1902, and was buried in the churchyard at Askeaton, co. Limerick.[3] As he never married, the name of de Vere at his death became extinct for the 2nd time, and was assumed by his nephew.[4]

Writing[]

Verse[]

His verse is intellectual, dignified, and imaginative, but somewhat too removed from familiar thought and feeling to win wide acceptance. A disciple of Wordsworth from the outset, he had a predilection for picturesque and romantic themes. He was at his best in the poems on old Irish subjects, and in his sonnets some of which, like "The Sun-God" and "Sorrow." reach a high standard of accomplishment.[3]

Sara Coleridge said of him that he had more entirely a poet's nature than even her own father or any of the poets she had known. His poetry enjoyed much vogue in America.[3]

Besides the volumes of verse cited De Vere wrote: 'The Infant Bridal and Other Poems,' 1864; 1876. 'Antar and Zara, an Eastern Romance,' 1877. 'The Foray of Queen Meave,' 1882. 'Legends and Records of the Church and Empire,' 1887. 'St. Peter's Chains, or Rome and the Italian Revolution,' 1888. 'Mediæval Records and Sonnets,' 1893.[3]

Prose[]

An accomplished writer of prose, De Vere was judged by R.H. Hutton to be a better critic than poet. His critical powers are seen to advantage throughout his Critical Essays (3 volumes, 1887-1889), but his correspondence with Sir Henry Taylor contains his best literary criticism.[3]

Other prose works are: 'Picturesque Sketches of Greece and Turkey,' 2 vols., 1850. ' The Church Settlement of Ireland,' 1866. 'Ireland's Church Property and the Right Use of it,' 1867. 'Pleas for Secularization,' 1867. 'Ireland's Church Question,' 1868. 'Proteus and Amadeus: a Correspondence about National Theology,' 1878. 'Ireland and Proportional Representation,' 1885.[3]

Critical introduction[]

Many people still remember with affection the venerable figure of Aubrey de Vere, most devout of Catholics and most amiably patriotic of Irishmen. His was “an old age serene and bright,” and at over 80 years of age he still retained the feelings and the instincts of a poet. But throughout the second half of his long life his 2 predominant passions were religion and Ireland; his poems written in these years, as he says in his Recollections, were almost exclusively "intended to illustrate religious philosophy or early Irish history." And these poems may almost be regarded as interludes in a life greatly occupied with the Irish political and economic problems of the time, to the discussion of which he frequently contributed.

But as a young man poetry — pure poetry — filled a much larger place in his thoughts and activities; naturally enough, for he was a poet’s son who up to the age of 20 had lived in almost daily intercourse with his father Sir Aubrey, whose poetical style and outlook, moreover — as will be recognized by any one who reads his plays Julian the Apostate and Mary Tudor — had a marked affinity to his own. In the days of his early productiveness, too, Aubrey de Vere mingled with the world of London and Cambridge, especially with the men of letters, such as Tennyson and Monckton Milnes, and above all with his intimate friend Henry Taylor. The Lives of several of these men abound with references to him, implying the most cordial intellectual intercourse; in that of Tennyson there are many and in Henry Taylor’s Autobiography many more.

Again, the 3 volumes of Critical Essays, which were written at many different dates though they were only collected in 1887-1889, show how deeply he had been interested in poetry and how excellent a critic he was. He tells us in his Recollections that Byron was his earliest admiration, but was instantly displaced when Sir Aubrey put Wordsworth’s Laodamia into his hands. It was with him as with Tennyson, in whose Memoir it is recorded that "he was dominated by Byron till he was seventeen, when he put him away altogether."

Laodamia converted de Vere; from that moment he was a Wordsworthian, though not an imitator; on the contrary the charming little volume called The Search after Proserpine, and other poems (1843) shows a gift more lyrical than philosophical, owing more to the influence of Shelley and the Greeks than to that of Rydal Mount. It is hard to find in his later writings anything so spontaneous, so musical as the best of these poems, and the volume shows de Vere in the stage when poetry filled his soul, when he saw that there were bigger things in the world, in history, and in literature, than the political problems of the day, and when even religion did not urge him to express her mysteries in verse. Seldom has the spell of Greece been exercised with greater effect than it was upon young de Vere, as he shows in the title-poem, and in Lines written under Delphi: poems which made old Landor, in 1848, beg him to “reascend with me the steeps of Greece” and to take no heed of Ireland — a country of which the old man writes in terms unfit for ears polite.

The curious thing is that this love for Greece and Greek tradition, which rings more true than anything in Childe Harold, seems to have clean passed away from Aubrey de Vere after he became possessed with the religious passion. There is not a single mention of the travels to Greece in the volume of Recollections, and in the well-known May Carols — May being the month of Mary — he admits that even the descriptive pieces are “an attempt towards a Christian rendering of external nature.”

The Coleridge poem is interesting both as an emotional utterance and as a piece of criticism; and the sonnets deserve their place as an expression of de Vere’s intense love for his father, of his regard for his brother poets, and of his religious faith.[5]

Recognition[]

His poems "Serenade" and "Sorrow" were included in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900.[6][7]

A colored drawing of De Vere at 20, showing a handsome countenance, and an oil portrait also done in youth by Samuel Laurence, are at Curragh Chase. An oil painting was done by Elinor M. Monsell (later Mrs. Bernard Darwin) when De Vere was 87.[3]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- The Waldenses; or, The fall of Rora. , London: John Henry Parker; Rivingtons, 1842.

- The Search after Proserpine, and other poems. Oxford: J.H. Parker, 1843.

- Poems. London: Burns & Lambert, 1855.[8]

- The Sisters, Innisfall, and other poems. New York: Longmans Green, 1861.[9]

- Innisfall: a lyrical chronicle of Ireland. Dublin, 1863.

- The Infant Bridal. London: Macmillan and Co., 1864.

- May Carols. London: Longman, Brown, Green, 1867.[10]

- Irish Odes, and other poems. : New York: Catholic Publication Society, 1869.

- The Legends of St. Patrick. London: H.S. King, 1872.

- St. Thomas of Canterbury: A dramatic poem. London H.S. King, 1876.

- The Fall of Rora; the Search after Proserpine; and other poems. London: H.S. King, 1877.

- Legends of the Saxon Saints. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1879.

- Alexander the Great, St. Thomas of Canterbury, and other poems. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1884.

- Poetical Works. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1884.

- The Legends of St Patrick. London: Cassell, 1889.

- Poems: A selection (edited by John Dennis). London: Cassell, 1890.[11]

- Selections from the Poems (edited with a preface by George Edward Woodberry). New York & London: Macmillan, 1894.

- Poems from the Works (edited by Margaret Domvile). London: Catholic Truth Society, 1904.[12]

Non-fiction[]

- Heroines of Charity. London: Burns & Lambert, 1854.

- Secret Specimens of the English Poets. London: Burns & Lambert, 1858.

- "Memoir of Sir Aubrey de Vere" in Sir Aubrey de Vere, Sonnets. London: Basil Montagu Pickering, 1875.[13]

- Ireland and Proportional Representation. Dublin, 1885.

- Essays chiefly on Poetry. London: Macmillan, 1887.

- Criticisms on Certain Poets. London: Macmillan, 1887.

- Essays chiefly Literary and Ethical. London: Macmillan, 1887.

- Religious Problems of the Nineteenth Century. London, 1893.

- Recollections of Aubrey Thomas de Vere. London: Arnold, 1897.

Edited[]

- The Household Poetry Book. London: Burns & Oates, 1893.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[14]

See also[]

Christmas Poetry & Hymn Collection A Christmas Carol, by Aubrey De Vere

References[]

Lee, Elizabeth (1912). "De Vere, Aubrey Thomas". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement. 1. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 492-493.

Notes[]

- ↑ John William Cousin, "De Vere, Aubrey Thomas," A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910, 114. Web, Jan. 3, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Lee, 492.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Lee, 493.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Smith, Helen Grace. "Aubrey Thomas Hunt de Vere." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 18 March 2016

- ↑ from Thomas Humphry Ward, "Critical Introduction: Aubrey Thomas de Vere (1814–1902)," The English Poets: Selections with critical introductions (edited by Thomas Humphry Ward). New York & London: Macmillan, 1880-1918. Web, Mar. 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Serenade", Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch), Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Sorrow", Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900 (edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch), Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1919. Bartleby.com, Web, May 4, 2012.

- ↑ Poems, Internet Archive, July 18, 2012.

- ↑ The Sisters, Innisfall and other poems, Internet Archive, July 18, 2012.

- ↑ May Carols, Internet Archive, July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Aubrey de Vere, Poems: A selection, London: Cassell, 1890. Google Books, Web, Dec. 27, 2021.

- ↑ Poems from the Works of Aubrey de Vere, London: Catholic Truth Society, 1904. Google Books, Web, Dec. 28, 2021.

- ↑ Sonnets (1875), Internet Archive, July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Search results = au:Aubrey Thomas de Vere 1902, WorldCat, Web, July 18, 2012.

External links[]

- Poems

- Aubrey de Vere in the Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1900: "Serenade", "Sorrow"

- "Implicit Faith"

- 3 poems by de Vere: "Christmas 1860," "A Christmas Carol," "A sweet exhaustion seems to hold"

- de Vere in The English Poets: An anthology:

- Extracts from The Search after Proserpine: "Fountain Nymphs," "Coleridge"

- Extracts from May Carols: "Stronger and steadier every hour," "A sweet exhaustion seems to hold," "A sudden sun-burst in the woods"

- Extracts from Medieval Records and Sonnets: "Browning," "Tennyson"

- Aubrey Thomas de Vere at PoemHunter (8 poems)

- de Vere in A Victorian Anthology, 1837-1895: "An Epicurean's Epitaph," "Flowers I Would Bring," "Human Life," "Sorrow," "Love's Spite," "The Queen's Vespers, "Cardinal Manning," "Song," "To Imperia"

- Aubrey Thomas de Vere at Poetry Nook (96 poems)

- Books

- Works by Aubrey de Vere at Project Gutenberg

- Aubrey Thomas de Vere at Amazon.com

- Works by or about Aubrey de Vere in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Recollections of Aubrey de Vere By Aubrey de Vere republished 2008

- About

- De Vere, Aubrey Thomas in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Aubrey Thomas Hunt de Vere in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Aubrey (Thomas) de Vere (1814-1902) at Ricorso

- More information on the life of Aubrey Thomas de Vere

- The De Vere family (.PDF)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Dictionary of National Biography, 2nd supplement (edited by Sidney Lee). London: Smith, Elder, 1912. Original article is at: de Vere, Aubrey Thomas

|