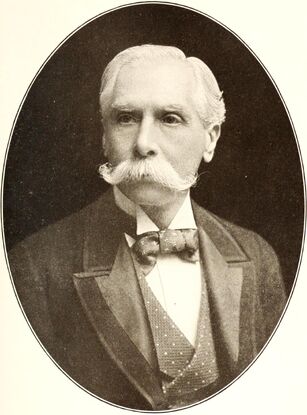

Alfred Austin in 1900. Photo by Louis Saul Langfier (1841-1919), from The Autobiography of Alfred Austin, 1911. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Alfred Austin (30 May 1835 - 2 June 1913) was an English poet who served as Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom.

Life[]

Youth and education[]

Austin was born at Headingley, Leeds, 30 May 1835. He was the 2nd son of Joseph Austin, a wool-stapler of Leeds, by his wife, Mary (Locke), sister of Joseph Locke, MP.[1]

Of a Roman Catholic family,[1] he was educated at Stonyhurst College in Clitheroe, Lancashire,[2] from 1849 to 1852, and then at Oscott College, University of London, from which he graduated with a B.A. in 1853.[1]

Career[]

Called to the bar by the Inner Temple in 1857, Austin joined the Northern circuit; but in 1858, having already published a verse-tale and a novel, he abandoned law for literature.[1] His father's death in 1861 left him with sufficient money to support himself by his writing.[3]

The meagre notice given in the Athenæum to his satire, The Season (1861), drew from him a sequel abusing that journal and its editor, William Hepworth Dixon.[1]

Austin's faith in his poetic genius wavered somewhat in 1862, when a narrative poem entitled The Human Tragedy, which he gave out as the 1st draft of a magnum opus, was coldly received.[1] "Austin immediately recalled the books and had it printed years later in a larger format." In a copy of the 1862 book he inscribed to author and publicist Laurence Oliphant, Austin wrote on the title page: "Withdrawn from circulation, to be altered + enlarged."[4]

He published no more verse till 1871, but turned again to novel-writing, though with little success.[1]

After his marriage in 1865 to Hester, daughter of Thomas Homan-Mulock, of Bellair, King's co., he sought an opening in political journalism. Running as a Conservative, he contested Taunton unsuccessfully in 1865 and Dewsbury in 1880.[1]

From 1866 to 1896 he was leader-writer to the Standard, and occasionally acted as its special correspondent abroad, for example at the Vatican Council of 1869–1870, with the Prussian army in 1870, and at the Congress of Berlin in 1884. His chief concern was with foreign affairs. An early enthusiast for Polish and Italian patriots, his hatred of Russia made him a devoted follower of Disraeli. In 1870 he rejoiced when the Prussian sword, ‘the World's salvation, smote its insulter to the knee’ (Interludes), and by 1876 he thought Garibaldi an ‘unmitigated nuisance’.[1]

In 1867 he had settled at Swinford Old Manor, near Ashford, Kent, in a domestic circle conscious of the privilege of cherishing a great poet. Feeling himself again ‘the adopted heir of Art and Nature’, he returned to poetry, and besides extending his Human Tragedy to the range of the ideal great poem, between 1871 and 1908 he published 20 volumes of verse.[1]

In 1883 he and William John Courthope became joint editors of the newly founded National Review, and Austin carried on the work for 8 years after Courthope's resignation in 1887.[1]

In 1894, a prose work, The Garden that I Love, achieved wide popular success; and because of this, or because of his journalistic services to Lord Salisbury's party, Austin was made poet laureate on 1 January 1896. Although the appointment was humorously criticized, the laureate's reverence for authority and for official ceremony gave him partial qualifications.[1]

To the end Austin believed that only the malice of critics and the odium theologicum prevented the world from taking him at his own high valuation. He never formally left the Church of Rome, but ‘vicarage gardens’ and ‘hamlets hallowed by their spires’ attached him sentimentally to the Church of England.[1]

He died without issue,[1] of unknown causes,[2] at Swinford Old Manor 2 June 1913.[1]

Writing[]

"The Laureate" - Austin caricature in Vanity Fair, February 1896. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Poetry[]

In 1861, after 2 false starts in poetry and fiction, Austin made his earliest noteworthy appearance as a writer with The Season: A satire, which contained incisive lines, and was marked by some promise both in wit and observation.[2]

As poet laureate, his topical verses did not escape negative criticism.[2] On the whole, his laureate pieces are better than most of their kind, although the earliest of them — an Ode in The Times (12 January 1896) hailing the news of the Jameson Raid — is as bad as the worst.[1]

Declared the Dictionary of National Biography: "His verse never frees itself from his admiration of Scott and Byron: but Scott never taught him the way to tell a tale, and Byron could not save him from invariably being 'an uncompromising moralist' (The Season). Not content with a talent for singing simply of country and countryside, he attempted to treat philosophic themes in epic and dramatic form. The Conversion of Winckelmann and Fortunatus the Pessimist are minor successes: but he had no gift for characterization and his narrative dwells inordinately on tales of sighing lovers 'with teardrops trembling on the cheek'. Perpetually revolving truisms, he could never give them the semblance of new or valuable truths."[1]

The most effective characteristic of Austin's poetry, as of the best of his prose, was a genuine and intimate love of nature. His lyrical poems are wanting in spontaneity and individuality, but many of them possess a simple, orderly charm, as of an English country lane. He had, indeed, a true love of England, sometimes not without a suspicion of insularity, but always fresh and ingenuous.[2]

Austin's poetics[]

Of more interest than Austin's poems are his poetics.[5]

Austin believed that melodiousness (musicality) and lucidity (clearness of expression) were essential to poetry.

- There must perforce be certain qualities common to all poetry, whether the greatest, the less great, or the comparatively inferior, and whether descriptive, lyrical, idyllic, reflective, epic, or dramatic; and, so long as there existed any authority or body of generally accepted opinion on the subject, these were at least two such qualities, viz. melodiousness, whether sweet or sonorous, and lucidity or clearness of expression, to be apprehended, without laborious investigation, by highly cultured and simple readers alike.[6]

- The most generous critic, if he is to be discriminating and just, cannot, let me say again, allow that any verse which is profoundly obscure or utterly unmusical, no matter how intellectual in substance, deserves the appellation of poetry.[7]

He believed that narrative poetry, whether epic or dramatic, was the highest or greatest form of poetry, and that great poetry must be narrative poetry. On his theory, as I understand it, poetry was about the mind's engagement with the world. According to him, there are 4 distinct ways in which a mind engages with the world: (1) perception, (2) emotion, (3) thought, and (4) action. Each succeeding stage of engagement is a higher form, in that it emerges from and incorporates those below it. The 4 classes of poetry, corresponding to the different stages of engagement, are (1) purely descriptive poetry (such as imagism), (2) lyric poetry, (3) reflective or philosophical poetry, and finally (4) narrative (epic or dramatic) poetry.

- Never forgetting the essential qualities of melody and lucidity, do we not find that mere descriptive verse, which depends on perception or observation, is the humblest and most elementary form of poetry; that descriptive verse, when suffused with sentiment, gains in value and charm; that if, to the foregoing, thought or reflection be superadded, there is a conspicuous rise in dignity, majesty, and relative excellence; and finally, that the employment of these in narrative action, whether epic or dramatic, carries us on to a stage of supreme excellence which can rarely be predicated of any poetry in which action is absent? If this be so, we have to the successive development of observation, feeling, thought, and action, an exact analogy or counterpart in (1) Descriptive Poetry; (2) Lyrical Poetry; (3) Reflective Poetry; (4) Epic or Dramatic Poetry; in each of which, melody and lucidity being always present, there is an advance in poetic value over the preceding stage, without the preceding one being eliminated from its progress.[8]

Prose[]

In 1870 Austin published a volume of literary criticism, The Poetry of the Period, which was conceived in the spirit of satire, and attacked Tennyson, Browning, Matthew Arnold and Swinburne in an unrestrained fashion. The book aroused some discussion at the time, but its judgments were extremely uncritical.[2] His criticism is profuse in the false attribution to others of precisely those faults which he failed to recognize in himself.[1]

His novels are thin in story, abundant in moralizing, and luscious in sentiment.[1]

His prose idylls, The Garden that I love and In Veronica's Garden, are full of a pleasant, open-air flavor.[2] Probably he is best in these 'garden-diaries', casual but often pompous jottings, half reverie, half autobiography, mainly devoted to the charm of his Kentish home or of his Italian holidays: they are not as solemnly sentimental as his poems.[1]

Recognition[]

Austin was appointed Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom in 1896, and served in that position until his death in 1913.

A drama by him, Flodden Field, was acted at His Majesty's theatre in 1903.[2]

There is a portrait of Austin by Leslie Ward ("Spy") in the National Portrait Gallery.[1]

In popular culture[]

Austin was caricatured as "Sir Austed Alfrin" by L. Frank Baum in his 1906 novel John Dough and the Cherub.[9]

Van Morrison's song "Haunts of Ancient Peace", the opening track on his 1980 album Common One, got its title from Austin's 1902 book Haunts of Ancient Peace.[10] [9]

Publications[]

Poetry[]

- Randolph: A poem, in two cantos. London: Saunders & Otley, 1855

- revised as Leszko the Bastard: A tale of Polish grief. London: Chapman & Hall, 1877.

- Shots at Shadows: A satire, but – a poem. London: R. Hardwicke, 1859.

- The Season: A satire. London: R. Hardwicke, 1861

- revised, London: Manwaring, 1861 [11]

- newly revised, London: John Camden Hotten, 1869.

- My Satire and its Censors. London: George Manwaring, 1861.

- Rome or Death!. Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood, 1873.

- The Human Tragedy: A poem

- 1st edition. London: Hardwicke, 1862

- 2nd edition (revised), Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood, 1876

- 3rd edition, London & New York: Macmillan, 1889, 1891.

- The Golden Age: A satire in verse. London: Chapman & Hall, 1871.

- Interludes. Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood, 1872.

- Soliloquies in Song. London: Macmillan, 1882.

- At the Gate of the Convent, and other poems. London: Macmillan, 1885.

- Look Seaward Sentinel! (chapbook). London: W.H. Allen, 1890.

- Love's Widowhood and other poems. London: Macmillan, 1889.

- A Betrothal, May 3rd, 1893 (chapbook). London: Chiswick Press, 1893.

- Madonna's Child. London & New York: Macmillan, 1895.

- English Lyrics. London & New York: Macmillan, 1896.

- Victoria, June 20, 1837 - June 20, 1897 (chapbook). London: Macmillian, 1897.

- The Conversion of Winckelmann, and other poems. London & New York: Macmillan, 1897.

- Songs of England. London & New York: Macmillan, 1898.

- A Tale of True Love, and other poems. London: Macmillan, 1902; New York: Harper, 1902.

- Victoria the Wise. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1903.

- The Door of Humility. London & New York: Macmillan, 1906.

- Sacred and Profane Love, and other poems. London: Macmillan, 1908.

Plays[]

- The Tower of Babel: A poetical drama. Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood, 1874

- reprinted as The Tower of Babel: A celestial love-drama. London & New York: Macmillan, 1890.

- Prince Lucifer. London & New York: Macmillan, 1887.

- Savonarola: A tragedy. London & New York: Macmillan, 1891.

- Fortunatus the Pessimist. London & New York: Macmillan, 1892.

- England's Darling. London & New York: Macmillan, 1896

- also published as Alfred the Great: England's darling, London: Macmillan, 1901.

- Flodden Field: A tragedy. New York & London: Harper, 1903.

- A Lesson in Harmony. London & New York: Samuel French, 1904.

Novels[]

- Five Years of It. London: J.F. Hope, 1858.

- An Artist's Proof. (3 volumes), London: Tinsley Bros., 1864. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- Won by a Head: A novel. (3 volumes), London: Chapman & Hall, 1866. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- Jessie's Expiation: A novel. (3 volumes), London: Tinsley Bros., 1867. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III

- The Lord of All: A novel. London: Chapman & Hall, 1867.

Non-fiction[]

- A Vindication of Lord Byron. London: Chapman & Hall, 1869.

- The Poetry of the Period. London: Bentley, 1870.[12]

- Russia Before Europe. London: Chatto & Windus, 1876.

- In Veronica's Garden. London & New York, Macmllan, 1895.

- Lamia's Winter-Quarters. London & New York: Macmillan, 1898.

- Spring and Autumn in Ireland. Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood, 1900. w\

- Haunts of Ancient Peace. London & New York: Macmillan, 1902.

- The Poet's Diary (edited by Lamia). London: Macmillan, 1904.

- The Garden that I Love. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1905.

- The Garden That I Love (Second series). London: Macmillan, 1907.

- The Bridling of Pegasus: Prose papers on poetry. London: Macmillan, 1910.[13]

- The Autobiography of Alfred Austin, Poet Laureate, 1835-1910 (2 volumes). London: Macmillan, 1911.

Collected editions[]

- Days of the Year: a poetic calendar from Alfred Austin. London: Walter Scott, 1886.

- Lyrical Poems. London & New York: Macmillan, 1891.

- Narrative Poems. London & New York: Macmillan, 1891.

- Love Poems. London & New York: John Lane, 1911.

Edited[]

- An Eighteenth Century Anthology (edited and introduction by Austin). London: Blackie, 1904.

Except where noted, bibliographical information courtesy WorldCat.[14]

Audio / video[]

Alfred Austin - A Poetry Sample

- The Poetry of Alfred Austin narrated by Richard Mitchley, Ghizela Rowe (audiobook). Deadtree Publishing, 2019.[15]

See also[]

| Preceded by Alfred, Lord Tennyson |

Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom 1892–1913 |

Succeeded by Robert Bridges |

Is Life Worth Living? by Alfred Austin (read by Tom O'Bedlam)

References[]

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Austin, Alfred". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 938.. Wikisource, Web, July 20, 2011.

Charlton, Henry Buckley (1927). "Austin, Alfred". In Davis, H.W.C. & Wheeler, J.R.H.. Dictionary of National Biography, 3rd supplement. 1. London: Smith, Elder. p. 15.. Wikisource, Web, Oct. 24, 2023.

Fonds[]

- Alfred Austin Papers, 1869-1902, Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 Charlton, 15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Austin, Alfred, Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911, 2, 938.

- ↑ Alfred Austin, My Poetic Side. Web, Nov. 4, 2023.

- ↑ The Human Tragedy, AbeBooks, American Book Exchange. Web, Nov. 6, 2023.

- ↑ c.f. Alfred Austin, "The Essentials of Great Poetry" in The Bridling of Pegasus: Prose papers on poetry (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1967). [Austin (1967)]. Project Gutenberg, Web, Nov. 2, 2023.

- ↑ Austin (1967), 2-3.

- ↑ Austin (1967), 7.

- ↑ Austin (1967), 9-10.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Alfred Austin, Wikipedia, August 13, 2023, Wikimedia Foundation. Web, Oct. 24, 2023.

- ↑ Peter Mills, Hymns to the Silence: Inside the words and music of Van Morrison. New York: Continuum, 2010, 338. Print.

- ↑ The Season: A Satire (1861), Internet Archive. Web, June 29, 2013.

- ↑ The Poetry of the Period (1870), Internet Archive. Web, June 29, 2013.

- ↑ The Bridling of Pegasus: Prose papers on poetry (1910), Internet Archive. Web, June 29, 2013.

- ↑ Search results = au:Alfred Austin, WorldCat, OCLC Online Computer Library Center Inc. Web, June 29, 2013.

- ↑ The Poetry of Alfred Austin, Amazon.com. Web, Feb. 14, 2020.

External links[]

- Poems

- "In the slant sunlight of the young October"

- Austin in A Victorian Anthology: "At His Grave," "Grave-Digger's Song," "Mother's Song," "Agatha," "The Haymaker's Song"

- Alfred Austin at Sonnet Central (6 sonnets)

- Alfred Austin at PoemHunter (235 poems)

- Alfred Austin at AllPoetry (245 poems)

- Books

- Works by Alfred Austin at Project Gutenberg

- Alfred Austin at the Online Books Page

- Alfred Austin at Amazon.com

- About

- Alfred Austin at NNDB

- Sources

- Alfred Austin (1835-1913) at the British Literary Ballads Archive

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain, the 1911 Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Original article is at Austin, Alfred

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Dictionary of National Biography, 3rd supplement (edited by H.W.C. Davis & J.R.H. Weaver). London: Smith, Elder, 1927. Original article is at: Austin, Alfred

|